The plight of asylum seekers is in sharp focus with heart-wrenching images of exhausted and terrified Ukrainian families forced into displacement. And while arriving at borders and seeking refuge is not new, the treatment of those forced to cross borders for asylum has rarely been so compassionate.

Even in a nation that prides itself on compassionate governance, an independent report into the detention of asylum seekers in New Zealand has found the worst of systemic abuse.

It turns out Aotearoa New Zealand has been detaining asylum seekers arbitrarily in criminal prisons, without charge or trial, for years now. What the independent report by Victoria Casey QC describes was no surprise to the community of people fighting to reveal this harrowing truth and asking successive governments to make it stop.

The Casey report documents a damning Kafkaesque nightmare, where those escaping persecution, torture and war are detained in New Zealand’s highest-security prisons unable to challenge their detention.

I still remember regularly seeing asylum seekers in the cells at Auckland’s district court, desperately trying to pass papers documenting their plight to duty lawyers through the slots of the busy meeting rooms. The duty lawyers are criminal lawyers, there to attend to those without representation in basic appearances before a criminal court. They generally lack the expertise or resources to put a case in refugee law.

Where they might, the judges of courts focused on drugs, violence and property crimes are rarely equipped to challenge the detention of a new arrival on refugee rights grounds. That’s part of what the Casey report found. Refugee lawyers are not resourced to act for their clients in a challenge to detention, and the criminal courts just never really listen.

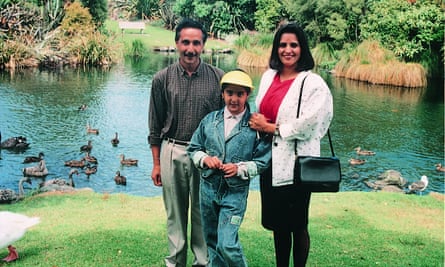

For me, as a lawyer and now lawmaker, the work of bringing to light asylum seeker detention has been personal. I imagined my anxious parents gripping my hand at Auckland airport when we first walked on “New Zealand soil” and told a man in what must have been a Customs uniform that we were refugees. They took us aside for a short interview, but first they asked if we were hungry. Then, as comes the most important national security threat to our island nation, they asked if we were carrying any fresh fruit or plant products. They gave us access to a lawyer and told us the process and sent us off to be assisted by the Salvation Army. We were welcomed, with access to our basic human rights.

The 100 or so asylum seekers whose detention is analysed in the Casey report similarly posed no national security threat or public safety risk that would necessitate their imprisonment. No lesser forms of detention, for example at the Mangere refugee resettlement centre (used to house quota refugees), or reporting requirements to police were prioritised. So what would have happened to my parents, Iranian political activists, fleeing the risk of torture, having lived through a war, here with a nine-year-old daughter they refused to raise under Islamic law? How would my dad fare at Mt Eden’s high-security remand prison?

Detained asylum seekers experience all the physical and psychological violence prevalent in our overcrowded prisons. They arrive with existing trauma and the wound is ripped open in a system that dehumanises them. Those I’ve spoken to report years of mental health struggles. They withdraw, become anxious and depressed, at just that moment when refugees normally experience relief and joy at being in our new homeland. They cling to one another, not necessarily from the same country of origin, religion or pre-asylum world, but with the same scars from New Zealand’s prisons.

What other group of people do we allow to be routinely imprisoned without charge or trial? Why do we presume asylum seekers to be a risk so high as to be locked up with our most dangerous criminals until proven innocent?

We already have a royal commission report into the events of the Christchurch terrorist attacks. The report told us our national security apparatus is prejudiced against just the kind of groups who are most likely to seek asylum, to escape war, to be targeted by white nationalism and repressive regimes back home.

Now the Casey report tells us again what systemic prejudice looks like. Importantly, the report calls not only for an end to arbitrary detention, but for proper resettlement resources to treat asylum seekers as equal to quota refugees. It repeats these are not “queue-jumpers”. The recommendations of the Casey report are what the Green party and the human rights and asylum seeker community have been demanding for years, and they are long overdue. The New Zealand government has accepted the report’s recommendations; now they must be implemented.

New Zealand said after the Christchurch mosque attacks: “This is not us.” It turns out that was more of a call to action than a reality at the time.

Treating refugees and asylum seekers with dignity, and implementing the recommendations of the Casey report, is the promise of that call.

Golriz Ghahraman is an Iranian-born Green party MP. She was the first refugee to be elected to New Zealand’s parliament