On the morning of 5 November 1881 my great-grandfather, Andrew Gilhooly, stood alongside 1,588 other men, waiting to commence the invasion of Parihaka pā (settlement), home to the great pacifist leaders Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi and their people. He would have participated in the weeks and months of destruction and despoliation – of people, property and cultivations – that followed.

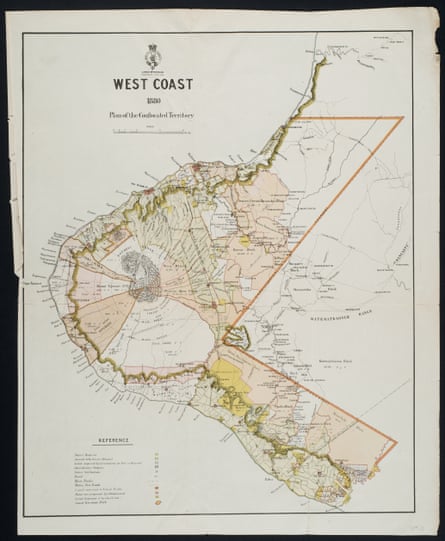

Andrew remained at Parihaka – which is on the west coast of the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand – as part of the Armed Constabulary’s occupying force until late 1884. The occupation was not benign: on one occasion constables tore down 12 houses in retaliation for attempts by neighbouring Māori to bring goods into Parihaka (the attempt to feed starving people was dismissed by the native minister as being “in every way objectionable”).

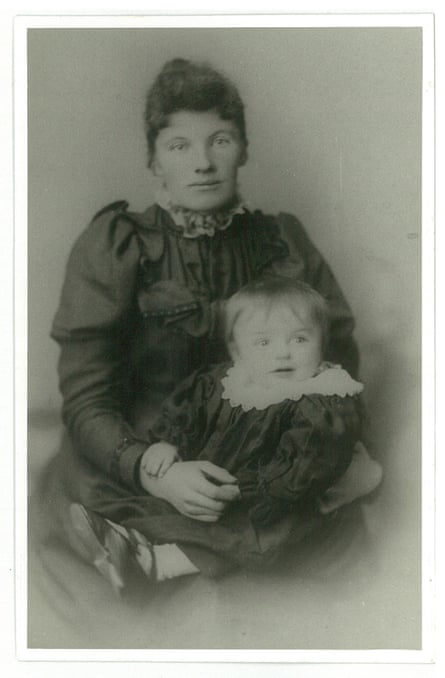

Having contributed to the military campaign against the pā, a decade later Andrew returned as part of the agricultural campaign to complete the alienation of the people of Parihaka from their land. Eventually, with his wife, Kate, he would control 400 acres of land comprising three family farms, each within just a few kilometres of Parihaka. Those properties were part of the 1,275,000 acres the colonial government had confiscated from its owners in 1865, and then granted or sold to military men and other settler farmers.

None of the many stories I know of my family’s years on the Taranaki coast include this detail. I have inherited an orthodox settler account, one which emphasises rights of belonging but which dances nimbly over the confiscation, theft and violence that made the farming possible. That other story – the unsettled one – does not feature in my history. For the better part of my life I have been quite comfortable with this. Recently, however, I have begun trying to end this personal silence. In doing so, I have stumbled upon some uncomfortable truths – one of which is my great-grandparents, whose migration to the Taranaki coast was driven by economic hardship caused by British colonialism in Ireland, were themselves part of a process of colonisation which had the same impact upon the indigenous people of this country.

Andrew was born in 1855, one of 10 children, the son of tenant farming people who paid £26 and 10 shillings a year to William Anderson – an English squire who lived in Devonshire – for the privilege of working a 29-acre tenement in Ballynagranagh, a small village in the parish of Kilteely, east County Limerick. In early 1874 he and his sister, Bridget, took assisted passage on board the New Zealand Shipping Company’s 800-ton clipper the Wennington, which sailed from Gravesend on 21 January and arrived in Wellington three months later.

By the time he died in 1922, following a 14-year-long military career, he and Kate held sway over 412 acres of land. That is 16 times the size of the small plot his own father had worked, and nearly 17% more land in total than the 362 acres the Devonshire squire owned in Kilteely parish. This extraordinary economic transformation is mirrored by a social metamorphosis – the family farms enabling my great-grandparents to cast off the class strictures of Ireland and become respected members of the coastal farming community. And it is all built on land that had been confiscated from its rightful owners.

The grim irony that my Irish family was involved in alienating Taranaki Māori from their land is hard to miss. The Waitangi Tribunal – a standing commission of inquiry into breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi – has pointed out that the confiscation of Māori land in Aotearoa was based on Irish precedents. For instance, the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 (the instrument used to confiscate the land Andrew and Kate would farm) was similar to Cromwell’s Act of Settlement 1652, while the Suppression of Rebellion Act 1863 was copied, virtually word for word, from the 1799 Irish law of that name.

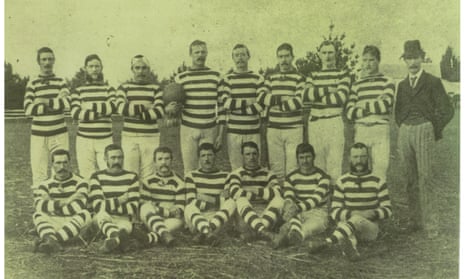

A prominent feature of the elephant in my historical room is that Andrew was a member of a military-policing force that was closely modelled on the Irish Constabulary. New Zealand historian Richard Hill notes that the Irish version was “infamous for its coercive mobile patrols, [and] able to concentrate en masse to pre-empt or suppress outbreaks of civil dissent, unrest or rebellion” among Andrew’s own Irish people. My great-grandfather served with a force that did much the same thing to the indigenous people on this side of the world.

Moreover, I am a descendant of a people with a history of violent subjugation, dispossession, famine and dispersal. Under Cromwell, who in 1649 picked up where the Tudors had left off, over 11m acres of Irish land were confiscated. Most of that land was granted to soldiers from the occupying English forces. By the mid-18th century land set aside for Irish Catholics amounted to less than 5% of the country’s total landmass, which is not far removed from the 11% of land from the Parihaka Block that remains in Māori ownership today.

Look at a map of Ireland circa 1650 and you will see an unsettling resemblance to one of Taranaki circa 1881. Right there are the gobbets of land ring-fenced for “Adventurers and Soldiers”, there the “Government Reservations” and over there the white bits set aside for the native Irish Catholics. The same administrative categories appear on the late 19th century cadastral maps of Taranaki, which also use white to denote land set aside for the indigenous people. As with the earlier Irish maps, those parts are also very small.

One other thing. In the west of Ireland there are famine roads, built – as Robert Macfarlane puts it in his book The Old Ways – in the 1840s “by the starving … to connect nothing with nothing in return for little”. My great-grandfather worked on a different kind of road in another country, one along which the Armed Constabulary marched to destroy Parihaka.

Following that invasion there was also ruination, privation and hunger, materially and in other ways.

When my people broke with their past by becoming landholders in their own right, they did so on the basis of the dispossession of another people. My great-grandfather got to be a farmer only because the land he farmed had been taken from Māori. But for me, it is the settlement story that prevails.

Richard Shaw is a professor of politics at Massey University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences. This is an edited extract from his memoir, The Forgotten Coast (Massey University Press, $35)