Even to Abbas Nazari’s disoriented seven-year-old mind, the faint “upside-down triangle” on the horizon represented one thing: salvation.

Weakened by dehydration and illness, battered by the terrifying storm that had incapacitated the small boat carrying him and hundreds of others, Nazari remembers staring over the sea at the ship that would rescue them.

“I can’t properly describe it: it was just a huge amount of relief, especially given what we went through the night before, an almost out-of-body experience, it was just incredible ... we were saved.”

That triangle was the MV Tampa, a Norwegian freighter that would sail to his and his family’s rescue, along with 426 other asylum seekers, mostly from Afghanistan, and then into Australian history. The Tampa would become the central player in an extraordinary legal battle, and shorthand for the genesis of a new generation of hardline border policies.

Thursday marks 20 years since Nazari’s dramatic rescue.

Much has changed in the two decades since, of course, but much remains: the Taliban is brutally ascendant across Afghanistan, wreaking violence and terror and sending thousands fleeing from the country. And the offshore processing network Australia set up in the wake of the Tampa is still operational. Those from the Tampa have left, but there are refugees held in those places still.

Nazari remembers vividly looking back off the deck of the Tampa at the stricken Palapa, the fragile wooden fishing vessel that had foundered in waters 140km north of Christmas Island, watching it break up and vanish under the roiling sea just minutes after all aboard had been rescued.

“There’s no denying the sheer raw emotion of being saved, especially given the night before. Of climbing the stairs, catching your breath at the top and then looking down to see the Palapa fall to pieces. That doesn’t need explaining to a child: a child can understand that.”

Nazari had fled Afghanistan with his mother, father and four siblings, including an infant, escaping their village of Sungjoy in the foothills of the Hindu Kush, ahead of an advancing Taliban and the wave of terror that swept before them.

The journey was wearying for a seven-year-old, his fatigue punctuated by moments of panic, and confusion about what they were fleeing and where they were going.

Over months, the family made its way via Pakistan to Indonesia, where they boarded the barely seaworthy Palapa. After four days at sea, battered by storms, the Palapa’s engine died a final death, and the vessel was adrift.

The Tampa changed everything

The fully laden Tampa was heading for Singapore when it received a distress signal to rescue the passengers on board the Palapa. Captain Arne Rinnan, under the direction of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, set a course for where the stranded Palapa had been spotted, guided by Australian planes.

Rinnan reached the Palapa on the morning of 26 August, a Sunday. Minutes before the Palapa disappeared into the ocean, his crew rescued everyone on board, including 43 children and three pregnant women. The law of the sea mandated he bring the rescued passengers ashore at the nearest port – Christmas Island. But Rinnan was instead instructed to take them to the Indonesian port of Merak.

A delegation of asylum seekers entered the ship’s bridge, urging the captain to take them to Christmas Island. Some threatened to jump off the ship.

Rinnnan reported that he did not feel threatened and was not at risk of losing control of his ship. Conscious too that the Tampa did not have enough lifejackets or rations for his new passengers, he turned the ship in a broad arc towards Christmas Island.

However, the Australian government refused the Tampa permission to land any of the asylum seekers on Australian soil.

The prime minister, John Howard, said: “I believe it is in Australia’s national interest that we draw a line on what is increasingly becoming an uncontrollable number of illegal arrivals in this country.”

Rinnan was threatened with prosecution. He turned the ship away from Christmas Island again. Again, he was petitioned by those on board. Their health was getting worse, and several had slipped into unconsciousness. Rinnan told Australian officials: “The medical situation on board is critical. If it is not addressed immediately people will die shortly.”

For a third time, the Tampa turned towards Australian waters.

Rinnan crossed Australia’s maritime boundary shortly before noon on 29 August. The Australian government advised him he was in “flagrant breach of Australian law”, and, when the Tampa anchored off Christmas Island’s Flying Fish Cove, sent aboard 45 SAS troops, who seized control of the ship.

Peter Tinley, second-in-command of the SAS that day, would later report he had been briefed for a potentially hostile and dangerous situation. Instead, he said, he found “400-plus ordinary refugees, very hungry, some who needed some medical attention, very scared and uncertain about what was happening [and] a particularly concerned sea captain who just wanted to offload his human cargo and discharge his duty according to international law”.

A handwritten letter was thrust into the hands of the Norwegian ambassador, who had also come on board: a formal request for asylum in Australia.

“You know well about the long time war and its tragic human consequences and you know about the genocide and massacres going on in our country,” it read. “We have no way but to run out of our dear homeland and to seek a peaceful asylum.”

In Canberra that evening, Howard introduced the border protection bill to parliament, giving the government sweeping powers to refuse entry to people seeking asylum by sea. The Act would be made retrospective to 9am that day, two-and-a-half hours before the Tampa entered Australian waters.

It would be the first in a suite of dramatic legislative and policy changes that transformed Australia’s asylum regime. Australia would legally excise Christmas and other islands from its territory for the purposes of migration; the defence force and border authorities would be given new rules of engagement to intercept and force boats back to Indonesia; and a “Pacific solution” was negotiated with Papua New Guinea and Nauru, allowing Australia to build detention centres on their islands.

The Tampa also changed the way Australia understood and spoke about the movement of people. Migration became an issue of “border protection” and “threats to national security”. Those arriving by boat were no longer “asylum seekers” but “illegals”. Ministers would publicly allege asylum seekers “could be murderers, could be terrorists”, and that “whole villages” were coming to Australia in uncontrollable “floods”. “Stopping the boats” would later be conducted in secret as “if we were at war”. The immigration and customs departments became the Australian Border Force.

The Tampa was the ship that changed everything, but the crisis did not exist in a vacuum.

It came at a time of escalating numbers of boat arrivals to Australia’s north-west – from 200 in 1998 to 5,516 in 2001 (though boat arrivals only ever represented about 1.5% of Australia’s total migration intake).

It was quickly followed by the “children overboard” scandal – where government ministers falsely stated children were thrown into the sea in order that they would be rescued and could claim asylum – and the tragic sinking of the SIEV X in which 353 people, mainly women and children, drowned.

Tampa also profoundly influenced a fiercely fought federal election that would return the Howard government with an increased majority.

And it came just more than a fortnight before the terrorist attacks of 11 September, the global cataclysm that would transform the next decades and profoundly change the way migration was perceived across the world.

‘We will decide who comes to this country’

Philip Ruddock was immigration minister when the Tampa arrived in Australian waters. He says he remembers a morning of urgent phone calls and a meeting with Howard before a cabinet meeting.

He says it was initially understood in Canberra that the Tampa would sail for Merak, before reports that Rinnan was “under duress … that he and his crew felt very much at risk” and he would head for Christmas Island.

“He was told he couldn’t bring the vessel into Australian waters, that he should turn around.

“The government determined that the ship was not to be admitted. The military was dispatched, really very much as a result of that, the expectation that the Australian government should succumb to whatever demands were being put on it. Our view was that that would lead to expectations that all you had to do was to arrive and you would get whatever you wanted.”

Ruddock said all the decisions that followed – “all of which were appropriate” – including offshore processing, excising islands from the migration zone and the introduction of temporary protection, were guided by that initial rationale to “maintain integrity” in migration processes.

Or, as Howard famously put it in a campaign speech later reprinted on thousands of election pamphlets: “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.”

Ruddock says now: “I don’t regard it as a matter of border protection. Rather it was a matter of maintaining integrity in helping those who need help most. I have a longstanding, passionate view about the need for Australia to be a humane country helping refugees who are most vulnerable.

“Today we have more than 80 million people displaced around the world, 30 million of those have been found to be refugees. To those who criticise our policies I ask: can we take them all? I assert if you can’t take them all, who do you take? Do you take those who have got money and who are free enough to travel, or do you take those who are the most vulnerable? Who are the people we ought to be resettling?”

Ruddock says he has dedicated much of his public life to helping refugees, most recently visiting displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh.

“I believe we should work to try to secure an outcome where people can return home safely and securely. I think we need to be putting a lot more effort into resolving situations of displacement than often we do as a world community.”

Ruddock says Australia should be proud of its long-running resettlement program – per capita one of the world’s most generous.

“I think the lessons of Tampa were that border integrity was appropriate, that it was successful, it stopped unauthorised arrivals,” he says.

‘A moment of moral reckoning’

Justice Tony North was the duty judge on the federal court when the Victorian Council for Civil Liberties filed an urgent challenge to the detention of those on board Tampa.

The judge remembers a dramatic, dynamic situation, the direction of the case repeatedly shifted by new declarations from the prime minister, new legislation being passed, and new developments from the deck of the ship.

“I was determined for the reputation of the federal court that the matter be determined very quickly,” North says. “There were people at sea, troops going on board, it was a minute-by-minute proposition. At one stage we were contemplating taking evidence from sea.”

In a judgment delivered just hours before the 9/11 attacks, North found the 433 people on the Tampa were unlawfully held there by Australia, which had “committed to retaining … complete control over the bodies and destinies of the rescuees”.

“The [government] directed where the MV Tampa was allowed to go and not to go. They procured the closing of the harbour so that the rescuees would be isolated. They did not allow communication with the rescuees. They did not consult with them about the arrangements being made for their physical relocation or future plans.”

At a distance of two decades, North’s position remains.

“I thought that if the law didn’t provide for the state to answer for holding those rescuees offshore in a confined space with nowhere else to go, that sounded contrary to legal principle.”

North says he sees parallels with the 1939 case of the MS St Louis, carrying 900 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. The ship was refused entry in Cuba, the US and Canada, before it was forced to return to Europe. Up to a quarter of its passengers would die in Nazi death camps.

North’s judgment was overturned 2-1 by the full bench of the federal court after the government appealed.

The court ruled – in the words of Justice Robert French, later chief justice of the high court – that the government could stop those on board the Tampa from entering Australia. “The power to determine who may come into Australia is so central to [Australia’s] sovereignty that it is not to be supposed that the government of the nation would lack the power … to prevent people not part of the Australia community from entering,” the judgment said.

As North points out, of four judges who heard the Tampa case, two decided in favour of the government’s action, two against. The result, he says, could easily have gone the other way.

“But if you stand back a little bit and take a helicopter view, what stands out now is that court case, as dramatic and significant as it was, has become something of a footnote, because we live under a system where parliament is sovereign. At the end of the day, parliament decided what it wanted to do, the government wanted to pursue its policies, and, in a failure of moral commitment, the Labor party fell in behind them.

“I saw that as a moment of real moral reckoning … You had a decision of the court that allowed the government to say ‘we will take the humane approach’. And that opportunity was missed.”

Stopping the boats

Tony Kevin, a former Australian ambassador and the author of Reluctant Rescuers, has spent decades charting irregular migration to Australia and the government’s response to it.

The government’s actions in the Tampa crisis were an outrage that damaged Australia’s international reputation, he argues.

“We took a commander of a major merchant vessel of Norway and we treated him like a criminal, we commandeered his boat by force, and we forced people he’d rescued to other countries, all in full view of the whole world. It was a huge insult to every law of the sea, to the safety of life at sea.”

But the debate over how Australia would deal with boat arrivals rolled on for years afterwards.

In 2013, more than a decade after Tampa, Tony Abbott came to power promising to “stop the boats”. Under Labor governments, offshore processing had been ended in 2008 and restarted in 2012. But the number of boat arrivals had increased to more than 20,000 in 2013, driven by regional and global unrest: Tamils fleeing the end of the Sri Lankan civil war, Rohingya fleeing state-sanctioned persecution in Myanmar, Iraqis escaping conflict.

Abbott’s plan, Operation Sovereign Borders, was “at the limit of the law and possibly beyond”, run with absolute secrecy “and deniability of on-water operations to protect the government from embarrassment”, Kevin says.

Boats were pushed back, towed back or their crews even bribed to return to Indonesia. If asylum boats were unseaworthy, Australia put asylum seekers in lifeboats and sent them back with just enough fuel to reach Indonesia. Australian ships illegally crossed into Indonesian waters to do it.

“The primary objectives were simple: no on-water deaths, and no forced acceptance of asylum seekers into Australian custody. Operational commanders were given to understand that Canberra would turn blind eyes to whatever had to be done to achieve these objectives – in Tony Abbott’s recent words, ‘whatever it takes’, and ‘by hook or by crook’, sum up what the government now expects of its OSB agencies.”

Critics of the policy argue pushbacks are an unambiguous breach of international law, potentially dangerous and fail to assess whether Australia is legally obliged to protect those intercepted.

Supporters, such as Kevin, argue boat interdictions have saved lives, prevented drownings at sea and ruined the people-smuggling trade which profited from the desperation of those seeking sanctuary.

He says government orders to aggressively intercept boats were welcomed by the navy and customs personnel who previously “had had to fish the bodies out of the water which they knew could have been saved and to confront the helpless grief and reproaches of the rescued”.

For years before, Kevin argues, it had been known that boats were coming, but that Australia had been a “reluctant rescuer … an entrenched doctrine that was actually murderous”.

But Kevin says corollary policies, in particular indefinite offshore detention, were an “unconscionable and resolute cruelty”.

A second chance

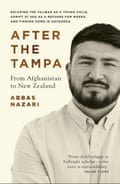

For Abbas Nazari, the Tampa was a brutality that brought a new life.

As those rescued waited on deck – Nazari remembers his skin blistering as he sat for hour after hour in the sun – New Zealand’s prime minister, Helen Clark, rang Howard. New Zealand would take up to 150 of the refugees, primarily women, children and family groups.

Nazari was among that group. After being taken on board an Australian naval ship to Nauru, he was flown to New Zealand, settling in “paradise” … a state-owned house in suburban Christchurch.

Nazari’s life since has been one of remarkable achievement. His family found its feet, then thrived in their new country: they were citizens within four years. In high school, Nazari placed third in a nationwide spelling bee (tripping up on “silhouetted”), then won scholarships to the University of Canterbury and a Fulbright scholarship to study at Georgetown University in the US.

“There are so many points where our lives could have turned out so differently,” Nazari says. “If the Tampa hadn’t been there to come to the rescue, if New Zealand hadn’t been so generous, if we’d sunk, if we had chosen to stay in our village: would I be alive or not? There are so many ‘what ifs’ in our story.”

Nazari has never been to Australia.

His New Zealand passport allows him unfettered access, but he has only ever transited through an airport on Australian soil.

But his presence, as a child, on the Tampa has given him a small part in a critical moment in Australian history.

For him, the legacy of the Tampa is acutely personal – a brutal experience “that I would never recommend anyone go through”, but one that has offered him, his family and his community “an incredible perspective on life”.

“You know, you go through this near-death experience, this harrowing journey, you come out the other side beaten and bruised but alive, and then you have the chance to make something of yourself.”

He is acutely aware that many were not so lucky. The majority of those on the Tampa were sent to Nauru, where they were held for years, before ultimately most were also resettled in New Zealand.

A few dozen came to Australia. Others, despondent at waiting and despairing at the uncertainty, acceded to being returned to Afghanistan.

On the 10th anniversary of the Tampa crisis, this reporter spent several weeks criss-crossing Afghanistan seeking out those who had been on board the ship and were returned to their homeland. They proved difficult to find, living subterranean lives in the shadows, practised at being inconspicuous.

But they were anxious to talk. They told stories of oppression, of marginalisation, of a caustic, constant fear.

Up to 20 Tampa asylum seekers had been killed on return to Afghanistan; others died trying to flee again.

One story in particular was told over and over again. Mohammad Hussain Mirzaee, a Tampa returnee and a former anti-Taliban fighter, was caught by insurgents in 2008 and dragged to his home village. In front of his family, he was beaten and thrown down a well. His tormentors threw a hand grenade down after him.

The hardening of hearts

With the Taliban again in control in Kabul, and ideologically unrepentant, the situation in Afghanistan now is as bad as it was in 2001.

As that conflict unleashes a huge new wave of refugees, the policy debates of Tampa echo around the world. Italy turns asylum seeker boats back to Libya “to block migration”; the UK contemplates offshore processing on distant islands, expressly citing the “Australian model”.

It’s a good time to ask whether the policies that flowed from Tampa have made the world’s most vulnerable safer, or simply forced the problem elsewhere.

Even excluding disruption caused by the pandemic, Australia now accepts fewer refugees for resettlement than it did under the government of Malcolm Fraser, when Australia’s population was much smaller, as was the global need.

Proponents would argue that the hardline policies have stopped unauthorised boat arrivals in Australia, prevented people drowning, and restored sovereignty and integrity to migration. Critics point to the widespread abuses of offshore detention, including deaths, and argue that the problem has merely been pushed over the horizon.

More than 14,000 refugees and asylum seekers are still stranded in Indonesia, caught there when Operation Sovereign Borders shut down the movement of boats from Indonesia to Australia. About 230 are still enmeshed in Australia’s offshore processing regime: most have been there more than eight years. Hundreds remain in detention in Australia.

Displacement is one of the defining characteristics of the 21st century. There are more people forced from their homes now than at almost any time in human history: more than 80m. The vast majority of the world’s refugees – 85% – are hosted by developing countries.

Nazari argues that attitudes towards irregular migration have hardened around the world. He says he is not an advocate for “open borders”, that he recognises the need for systems, for processes and for control. But he argues that for many around the world there is no queue, no chance for orderly migration.

Debates over migration have been corroded by political opportunism, migration used to “denigrate and dehumanise and divide people” by parties willing to “throw that immigrant dog whistle out there because it gets votes, it invigorates people”.

“In policy circles, it’s almost like a tap. You can just turn it on and off. And it’s just numbers. But then when you look at it holistically, you start seeing the complex reasons why people move. Some people are forced to flee. There is no system for those people. Some people have lived in refugee camps for decades, some have had to flee because of our action, particularly with regards to climate change. So when you start to have that conversation, then it becomes incredibly complex.

“The very easy, very simple solutions: they just don’t work.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion