Explainer - The Budget is approaching. From the way politicians, journalists, pundits and businesspeople talk it's like a secret society having the party of the year, but surely it's just numbers and columns?

What actually is it? Is it really that important? Can I even do anything about it?

RNZ is here to clear it all up.

Photo: RNZ / Vinay Ranchhod

What is the Budget?

In simple terms, the government's Budget (with a capital B) is just like a household budget (lower case b) on a larger scale.

It's an assessment of how much money the government has - taking into account debt, and income from tax and other things - and sets out the things the government plans to spend that money on.

In a technical sense, it's also a Bill - a proposed law - which the government needs to get approved by Parliament each year.

This can involve the governing party having to negotiate with its coalition partners. This means it's also a bit of an advertisement for the ruling parties who get to show off their spending promises and ability to get them done.

By the same token however, it can backfire for those parties if the ideas are unsuccessful, unpopular, or poorly implemented.

That sounds … kinda boring, why should I care?

Yes, the Budget does involve a whole lot of numbers, but it has a huge effect on people.

It is what keeps the trains running, and hospital buildings working, allocates funding for schools to stop them getting mouldy, and is why the government would consider restricting pay for public servants, including doctors, nurses, police and teachers.

It builds and maintains roads, helps combat climate change and child poverty, funds medicines and mental health services, and is what helps people who are down on their luck.

It also matters because the public are in large part the ones paying for those services. All these requirements dictate how much money the government needs, and as a result it may decide to reduce or increase taxes.

That includes on income taxes paid through people working; the sale of goods and services (GST); and tax on financial transactions.

The government also gets some money from other sources, like duties on alcohol, cigarettes, and state-owned enterprises like power companies and Air New Zealand.

It reveals all this spending on Budget Day, which comes with various ceremonial bits and pieces, and a big speech from the finance minister to Parliament after the lockup.

The lockup? Is that a prison for governments that ran out of money?

Well, no.

The lockup is where journalists reporting on the Budget get locked into a big room for several hours with all the Budget documents a few hours before they're publicly released.

At 2pm on Budget Day the doors and wifi connections are opened, the embargo (a media agreement not to publish about it until a certain time) lifts, and the Budget becomes public knowledge, accompanied by the journalists' reports on it.

The finance minister also gives a wee presentation to the journalists during the lockup, giving his take on the Budget. But it is access to the full documents they are mostly working from.

Once the reporters have had a go, the commentators get stuck in - sometimes with criticism, occasionally with praise, usually a mix of the two depending on who it is.

The other political parties also get in on the action. Sometimes they just criticise the government's decisions, other times they propose ideas of their own.

Well what does happen when governments do run out of money?

In balancing the books, the government tries to reach a surplus (having more money than is being used) to avoid a deficit (having not enough money).

Sometimes they will also want to spend extra money, in the hopes that doing so will keep the economy strong. If the economy gets weak, there's less money for people, and less money for the government to spend.

Recent Budgets have also been focused on more than just keeping the economy going, with the government arguing that other things, like the standard of living, are important to keep track of too.

Usually, governments that don't have enough money to spend on all the projects they want will simply borrow it, and go into debt.

Government debt is important for the government to keep track of, as it affects how easily it can borrow more money in future.

Interest rates have been very low, making borrowing cheap and going into debt less risky, and New Zealand is very highly rated so it's not really something the country needs to worry about too much in the short term.

It is important to maintain that high rating by continuing to pay off debts, however, to continue to be able to borrow when needed.

How do they decide what to spend the money on? Do they just argue about it? Can they just change their minds?

Ahead of Budget Day, the government puts work into the preparation with various ministers making requests for their areas of responsibility.

All the decisions are informed by the needs of the various departments and things that need maintenance or more spending to bring up to the standard people expect, along with the government's policies, and the financial realities.

It then decides on the general direction of its spending and advertises this with a Budget Policy Statement (BPS).

That said, plenty of things can happen which can throw the government's plans into disarray (not least a global pandemic), and the finance minister and the Cabinet get the final sign-off on the plan before it goes before Parliament.

Is that the end of the process? Who follows the money?

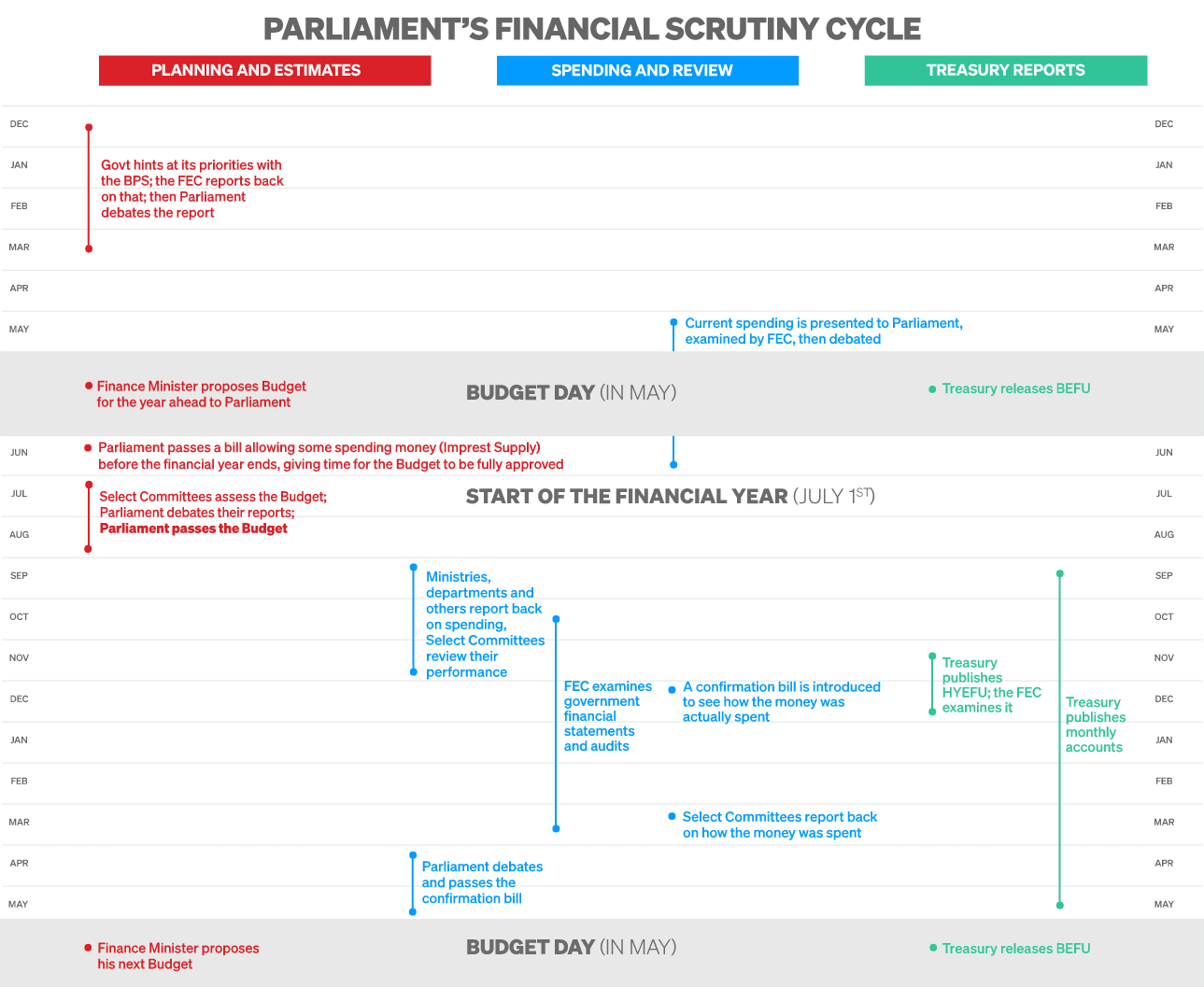

Budgets and debates about them in Parliament continue long after Budget Day, in a never-ending cycle that takes each Budget two and a half years to complete.

Chart: RNZ/Vinay Ranchhod

The general process includes the "Budget Day" in May, but it will continue to be criticised, examined and scrutinised by Select Committees, the Finance and Expenditure Committee (the FEC, a Select Committee), the Treasury, the Auditor-General, and Parliament itself.

The actual Budget bill gets finally passed in July, and in fact, Parliament only finishes debating the Budget from two years previous shortly before Budget Day.

Treasury is also required to report on the country's actual financial position as this process continues - once on Budget Day in May with the Budget Economic and Fiscal Update (BEFU); once again in December with an assessment which updates forecasts (but not policies) called the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU); and a one-off Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Update (PREFU) every three years, so all the campaigning parties know what finances the government is playing with.

It also publishes monthly updates on the government's finances.

Sounds like it's all taken care of then... Do I need to do anything?

Thankfully, yes, most of this work gets taken care of for us, but it's worth keeping track of the Budget announcements to see whether you agree with what the government is doing with your hard-earned cash.

And if you don't like it? Vote, petition, lobby, or otherwise engage in the political process.