For years Māori journalism leaders warned a lack of training, investment and opportunities meant Māori people and perspectives were mostly missing in our media. But more effort and money than ever before is now being put in. On Waitangi Day, Mediawatch talks to some of those involved in a publicly-funded push to address this - and some of the problems.

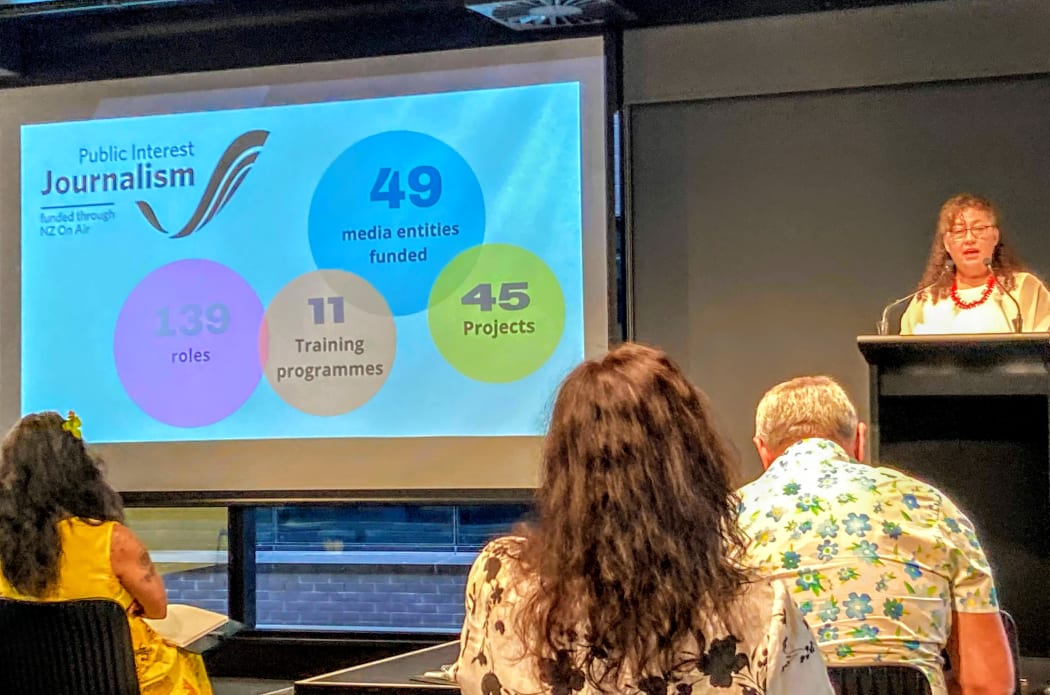

NZ on Air's head of journalism Raewyn Rasch outlines how the Public Interest Journalism Fund has been spent so far. Photo: photo / RNZ Mediawatch

“There are holes. There should be more Māori voices in mainstream media across the spectrum from regional newspapers to our bigger media outlets. We have a long way to go,” Leonie Hayden told Mediawatch after Waitangi Day back in 2016.

Back then she was the editor of Mana, the groundbreaking current affairs magazine founded more than 30 years earlier.

Now she’s leaving a hole herself, stepping down as editor of Atea, the Māori and indigenous content channel of digital media outlet The Spinoff.

Announcing her departure recently she said Māori journalism had “fallen between the cracks” with the government’s broadcasting funding agency NZ on Air - and Te Māngai Paho, which is focused on funding Māori broadcasting and te reo.

“But all of a sudden that’s not true,” she added.

“It’s a strange time to be dropping out of the media, just as it’s flooded with public money for Māori reporting roles - and there are too few experienced journalists to fill them.“

One reason for that is the government’s Public Interest Journalism Fund launched last year to inject $55 million over three years into “at risk journalism.”

It’s run by NZ on Air whose website says it allocates “a relatively modest proportion” of its budget to Māori content “because of the significant public funding available for Māori content provided through Māori Television and Te Māngai Pāho.”

But Māori media was central in its PIJF plan from the start.

NZ On Air pledged to work with Māori journalism to - in its words - “ensure parity of need and interests.” Guidelines issued early on declared the fund “must actively promote the principles of ... Te Tiriti o Waitangi" and invited proposals “made by Māori about Māori perspectives, issues ... prioritising the needs of Māori.”

Forty percent of the first funding round last July went to projects benefiting Māori journalism.

Some were small scale. Rotorua Weekender and a Salient student magazine were funded to print weekly bilingual sections.

Some projects were much more ambitious.

Photo: supplied

The Te Rito scheme to train 25 new journalists and cadets - costing up to $2.4m - is now up and running, backed by four major media companies with seven others as partners.

Radio Waatea - the biggest and most established station in the iwi radio network - got funding for new staff and $430,000 to turn its interview-based news show Paakiwaha into a daily current affairs show.

Several major media outlets have also secured six-figure sums from the PIJF for ‘partnership editors’ to ”change how the media engage with Māori and diverse audiences.“

Bottlenecks emerge

Graham Pryor, Radio Waatea general manager. Photo: supplied

But - as Leonie Hayden noted in The Spinoff - all this new commissioning, training and funding has created an immediate problem: a shortage of journalists for all these projects.

This was aired at a recent NZ On Air summit and a subsequent hui of Māori journalists association Kawea te Rongo.

“We've been successful in the Fund with seven new people starting ... but it's definitely been a challenge hiring Māori staff for the programmes we're setting up and new news roles,” he told Mediawatch.

“It's a good thing for Māori journalists coming back into the industry or coming to the industry new and starting to train - but now that there's more investment being made into the sector, Māori journalists are not there in the numbers that are required,” he said.

“Māori media has been significantly underfunded for a long, long time - and when you run out of resources, one of the first things that gets cut is training. And that's happened across the mainstream media as well,” he said.

Pryor’s Radio Waatea is also funded by Te Mangai Paho to supply news to the 21 iwi radio stations in the network Te Whakaruruhau.

TMP has funded Māori news for a long time - and its current co-funds Māori projects with NZ on Air as well.

So does the PIJF double up on TMP’s own work when it also funds Māori projects?

“I think that it's in addition to (what we do). We can't prioritize that amount of funding for one specific genre of content because we are still underfunded, we haven't had a funding increase for a number of years,“ said TMP’s head of content Blake Ihimarea, who’s been consulted on the applications for the PIFJ’s funding.

“But we're able to offer this opportunity and advocate for the Māori media sector and provide another opportunity for the working journalists and for agencies in organizations who are interested in producing content,” she told Mediawatch.

Even more public money is in the pipeline already.

Last year the government announced another $42m for Māori media content in the next four years.

“It will grow the capability of the Māori media sector and iwi radio to ensure that the sector has the appropriate skills . . and opportunities for Māori in a critical growth industry,” Peeni Henare said at the time.

Kelvin Davis put some numbers on it. He said this funding could create 102 hours of content and up to 940 news and current affairs stories.

Alongside broadcaster Stacey Morrison, RNZ’s former Māori issue correspondent Mihingarangi Forbes, has been training workers and contributors at iwi radio stations around the country in journalism in a special programme called Kōmiromiro - funded through the PIJF.

So why is it only now training programmes are beginning from scratch?

Stacey Morrison and Mihingarangi Forbes at NZ on Air's recent summit. Photo: photo / RNZ Mediawatch

“RNZ has a long, long, long history. For 50 or 60 years (it has) been able to build staff and capacity. When you consider Māori Television started in 2004, that's not so long ago,” she told Mediawatch.

“It has the same expectations as other channels to produce the news and get the unique stories - and be a champion for Māori broadcasting, but you just don't have the same resource or the same capacity. It's just too much of a stretch, in my opinion,” she said.

“I'm probably one of the last to have a cadetship at TVNZ and that followed a good ten years of really intense good training over there. At the time Māori and Pacific programmes took up a whole wing of TVNZ and there would have been about 100 people working there. We haven't really had anything like that since then,” said Forbes, the current host of TV current affairs show the Hui and Māori politics show Party People (also funded with $236,000 via the PIJF).

Partnership and te Tiriti principles

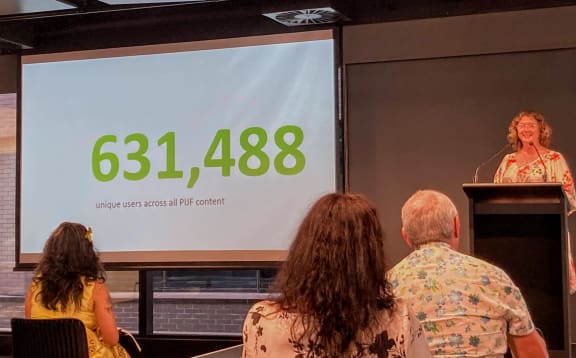

Cat Goodwin - NZ on Air's audience and media strategist - says more than 600,000 people have read, heard or watched output of the PIJF. Photo: photo / RNZ Mediawatch

Mihingarangi Forbes is also the co-founder of media company Aotearoa Media Collective which promotes the concept of Partnership Editors - paid for by the PIJF - as a means of incorporating te Tiriti o Waitangi principles.

“Many media organisations do not understand Te Tiriti and the conversations they are curating run the risk of being biased, racist and not delivering to the Te Tiriti partner - Māori or tangata whenua,” Rasch told Mediawatch last July.

“Partnership editors’ will sit at the executive level like any other executive and help shape the news agenda for whichever news organisation they’re part of. That hasn’t been there so far and that’s a deficit,” she said.

(TVNZ appointed an executive-level Kaihautu in 2003 who served until 2007)

But some commentators reckon that’s inconsistent with the essential independence of news and media - and others argue media companies ought to pay for their own editors.

Will a partnership editor edit or censor news stories if they don’t think principles of te Tiriti have been incorporated properly?

“I'm worried about people thinking ... there was anyone sitting at a computer saying: ‘You can't say that’. Or: ‘Say that this way.’ I doubt if that would ever happen. And I hope it doesn't,” Forbes told Mediawatch.

“A partnership editor can be whatever you need it to be. Some organisations like TVNZ have already got a Māori plan in place so they will need will be completely different from somebody who's just beginning the journey and it will make the place a better place to work ... for all reporters,” she said.

But partnership editors will surely exercise editorial powers where they think reporting or media practice is wrong - or worse - racist?

”We're already doing that - and the only reason that we're allowed to be in those newsrooms is because we're journalists. And that's the problem, because there’s only a few of us, and we can't do everything ... bringing mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) to a newsroom,” she said.

So if you are media editor or executive - do you really want a partnership editor at your side telling you whether you’re abiding by treaty principles and incorporating matauranga Māori - or not?

NZ Geographic editor Rebekah White and Kowhai Media publisher James Frankham. Photo: photo / RNZ Mediawatch

Kowhai Media’s James Frankham - formerly publisher of Mana Magazine - does.

His company has already identified its Kaiwhakatika Hourua - Nick Low, previously a contributor to Kowahi’s main publication New Zealand Geographic.

“He will help us to give Māori stories the prominence that they deserve ... and to tell them in a way that we haven't been able to tell them before,” Frankham told Mediawatch.

“We hope will be transformative, not just for the way that we do journalism but also for the way in which we run the media company, You need to understand your own roles and responsibilities and you might as well make those changes and get on the forefront of this,” he said.

“I would say that journalistic freedom isn't very free if you only have access to half the story, because you don't have the relationships or the understanding to be able to access the other half of society,” Rebekah White, the editor of New Zealand Geographic told Mediawatch.

The PIJF is the biggest single boost to media funding for decades, but like other Labour-led government interventions in media in recent times it is not a long term strategy or commitment. Opposition political parties have condemned it.

“It has to serve the public interest to do this work - not just something media organisations can take advantage of as a handout. What else should the government be promoting? Things that benefit the public and benefit taxpayers and allow us a better vision of who we are as a society and where we're going,” said James Frankham.

Photo: supplied