There has been controversy over the lack of uniformity in the allocation of points to qualify for various procedures, district health board (DHB) targets for elective surgery which affected funding and prompted accusations of game playing, efficiency projects supposed to cut waste and speed things up, and upsets over patients still in agony directed back to their general practitioner because they were not deemed to meet the threshold for treatment.

Concerns about short staffing, both in terms of nursing and senior doctors, never seem to have been far away, and some hospital facilities are below par, including those in Dunedin.

Demand always exceeds supply, and that is before any consideration is given to the poorly measured unmet need where prospective patients never get within cooee of a waiting list.

It is a big call now for the taskforce, led by Auckland colorectal surgeon Andrew Connolly (whose other roles include chairing Southern District Health Board’s endoscopy user group) to come up with a national plan by September for what is being called ‘‘planned care’’ — appointments or procedures that are not urgent (although the long-suffering patient might feel otherwise) and can therefore be scheduled or planned.

The figures on the list are astounding. In March nearly 36,000 people had been waiting longer than four months to have their first appointment with a hospital specialist to assess their condition, more than twice as many as in the February before the pandemic measures struck.

The number of patients waiting longer than four months for treatment has more than trebled, from 8153 in February 2020 to 26,764.

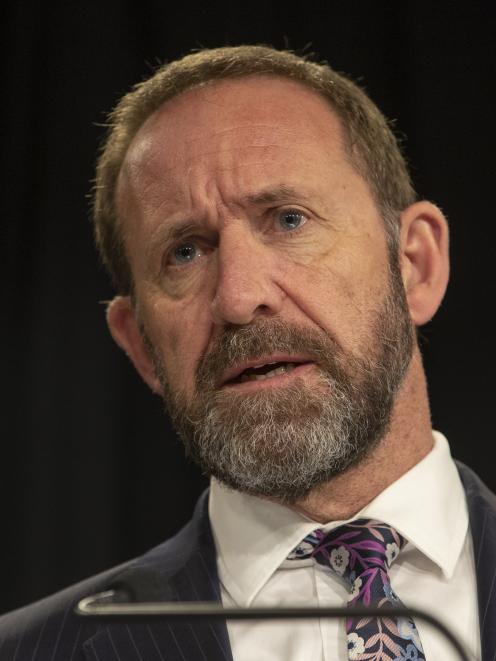

Health Minister Andrew Little boldly says this new, national approach to specialist appointments and planned-care operations will get rid of the postcode lottery that has seen people treated differently in different parts of the country once and for all.

It makes sense for Mr Little to be seen to be doing something about this issue now rather than leave it until the dismantling of the DHBs which, if all goes to plan, is mere months away.

But there will be considerable hurdles to overcome, not least ongoing short-staffing around the country.

Greater use of private hospitals to undertake some standard procedures, rather than calling on them in desperation as has happened in the past when public hospitals were snowed under, should allow for the development of long-term contracts with more sensible prices.

There will have to be good communication between public and private hospitals and clear understanding about responsibility for post-operative care.

The notion more people than usual will have to travel to other parts of the country for timely treatment may not always be welcomed by patients, for a variety of reasons, and we would hope it would not be presented as a take it or leave it choice. What funding might be provided to support patients who travel and their families will also have to be spelled out.

Many on existing waiting lists are likely to wait a while longer to see much action. While it is good to see emphasis on better access to effective alternatives to surgery, some may be dismayed at this if they have their hearts set on surgery and consider they have already exhausted other possible remedies.

However the taskforce’s plan pans out, this national approach is a sign of things to come under the health reforms. And, like any big health issue, it runs the risk of becoming more about politics than patient care.

Comments

Nothing here addresses the underlying problem; lack of staff and lack of resources. The waiting list is very misleading, as there are thousand who should be on the waiting list but get rejected by DHBs even though GPs know they need treatment. The Ministry of Health, district health boards, Medical Council of NZ and Ministry of Immigration need to work together. There are experienced staff out there who cannot get into the system because of lack of places.