Analysis: Imagine a typical primary school classroom. The teacher, at the front of the room, takes a long drag from a cigarette and then begins their lesson, sending a plume of smoke across most of the room.

How many of the kids can see it? How many can smell it when they breathe in?

And what would happen if there was a fan in the room, or a couple of open windows creating cross-flow to help aerate the room?

These are the issues that teachers, health experts, parents and government officials are grappling with in anticipation of community spread of Covid-19, even though school-age children may not be able to be vaccinated until next year. Those conversations have only become more urgent with the announcement that schools in Auckland and the Waikato will reopen on Wednesday.

They also flag the importance of air quality beyond the school environment – ventilation and filtration in a wide range of venues could help dampen transmission of the virus and allow other, more onerous restrictions to be lifted.

“If we’re going to be living with community transmission of Covid, we really need to start thinking about what the air is like in the indoor environments where we are. Schools are the first group that are going back in, other than your essential workers, and I guess the next step is going to be businesses,” says University of Otago public health expert Julie Bennett.

Bennett has spent much of her career researching the links between indoor air quality, housing and health. She says that Covid-19 has only bolstered the significance of rethinking our approach to air quality, but that we can expect to see other benefits as well, including a lower winter disease burden and increased productivity in schools and workplaces.

“Having good ventilation in classrooms is great, because if you don’t have high levels of carbon dioxide, the children aren’t going to get as sleepy and they’re going to be able to learn better,” she says.

“Improving the indoor environment has a lot more benefit. Covid is one aspect, but there are a whole lot of other aspects that are positive on health.”

And Otago’s Amanda Kvalsvig, who was the lead author of a new, pathogen-neutral pandemic plan for New Zealand, says she is desperately hoping that the Government will take air quality seriously in the future.

“It’s enduring. If you get it right, it will stay right for years. This is our transition out of the pandemic and this should be our legacy.”

Ask Kvalsvig and Bennett what their ideal world looks like and they describe a total rethink of air quality in buildings. That means much greater awareness around the ventilation in a given room and a potential overhaul of ventilation and filtration in offices, schools, homes and venues where a lot of people gather in close quarters.

The winter disease burden could be eliminated. RSV could be stopped in its tracks. Children could learn better with clearer air. Workers could think better. And with fewer people ill, less work and less learning would be lost to sick days.

Fixing New Zealand’s air quality issues could give an immense boost not just to the nation’s health, but to its productivity as well. But that would require a commitment from the Government for transformation – something it hasn’t been keen on thus far. Kvalsvig’s hope is that maybe, just maybe, the threat of Covid-19 will be enough to kickstart these changes and the obvious co-benefits will ensure that the Government sees them through to the end.

Covid-19 is airborne

Kvalsvig is loath to recall the heated scientific and political debates over whether SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the Covid-19 disease, can infect people by air. Over much of 2020 – and, in New Zealand, well into 2021 – governments shied away from the evidence of airborne transmission, focusing instead on short-distance droplets and the risk of infection by surfaces.

While not as public domestically, the debate still took place here as well. Take the so-called bin lid transmission in a Christchurch MIQ facility. Health officials said someone may have been infected by touching a bin lid shortly after an infectious case had done so. This would have been the first confirmed case of fomite transmission – where someone is infected with a surface as an intermediary – anywhere in the world.

It took subsequent work by independent researchers to determine that the transmission was in fact due to aerosols – tiny viral particles that can float for several minutes and travel long distances on air currents. Just 50 seconds after the infectious case was tested, their neighbours opened their door to be tested. The virus was likely sucked into the room and infected them there, due to poor ventilation and the net-positive pressure between the room and the hallway.

In New Zealand, as elsewhere, the early airborne debate revolved around the efficacy of masks. If the virus only spread through surfaces and through short-range droplets, then social distancing alone should be sufficient to reduce spread. But masks turned out to be highly effective, indicating that they were either blocking longer-range, smaller droplets, or reducing the spread of infectious aerosols (in reality, they probably do a bit of both).

The Ministry of Health was slow to adopt the evidence on masks and slow to stop chasing fomite red herrings. But by August, it had finally come on board. In an August 17 press release, it said an investigation of another case of within-MIQ transmission was found to be due to doors across the hallway from one another being opened for three to five overlapping seconds on a handful of occasions.

And when it came time to step down restrictions in Auckland, the Government began to separate outdoor and indoor activities, saying the former were far less risky because of the vastly better air quality.

“There’s only a slow recognition that Delta has airborne transmission and that ventilation has become a really key component of how we’re going to combat this,” says developmental paediatrician Jin Russell.

The cigarette metaphor is a useful tool for understanding aerosol transmission. You’re far less likely to inhale someone’s second-hand smoke outdoors than you are indoors. In essence, if you’re worried about airborne transmission, the key is to make sure you’re not breathing in the same air that someone else is breathing out.

“It’s now accepted that SARS-CoV-2 can hang in the air and attach to other particles. It can do this and linger in the air for long periods of time,” Bennett says.

“When it’s in an indoor environment, these particles can become more concentrated and they aren’t able to escape. That’s when ventilation becomes more important, because you want to change the air from inside the building and replace it with air from outside the building.”

Filtration can also help – that removes infectious particles from the air, making rebreathing not so dangerous anymore. But ventilation will be one of our main tools in fighting the virus in the next phase of the pandemic.

Why ventilation?

Clearly, ventilation is effective at stopping Covid-19. But when we have so many other tools available to us, from vaccination to masks to contact tracing and a variety of tests, why should ventilation be prioritised?

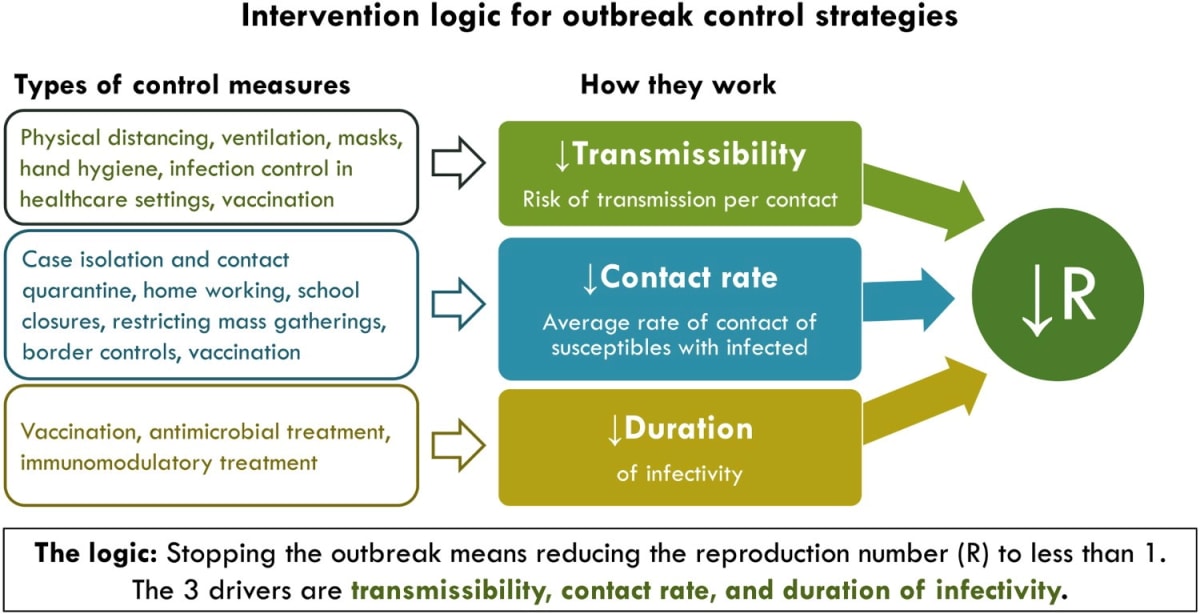

Here, Kvalsvig points to her new pandemic plan for New Zealand, which examines the intervention logic for each available tool.

There are roughly three types of measures to control an outbreak – ones that reduce the risk of transmission for each contact between people, ones that reduce how often infected people contact vulnerable people and ones that reduce the length of infectiousness. The latter are key, as through vaccinations and proactive treatments we can stop outbreaks without relying on measures which affect the wider population.

But they aren’t always available – vaccines took a year to develop – and they aren’t always perfect. Modelling from Te Pūnaha Matatini, released in September, found that even with high vaccination rates of 90 or 95 percent, additional measures would be needed to stop Covid-19 from spreading out of control.

In this scenario, the first type of measure is the most important. If we want to live some semblance of a normal life in 2022 and beyond, we don’t want to adopt measures that reduce contact between people. Things like lockdowns, closing schools and capacity limits aren’t sustainable in the long term – the experience in Auckland has shown that.

Instead, tools like masks and ventilation allow us to come together, but in slightly different ways.

“The intervention logic for ventilation as a Covid control measure is very powerful because it gets so close to how transmission actually happens. At its very most basic level, you’ve got somebody who’s infectious and breathes out, somebody who’s susceptible breathes in, and that’s how they become infected,” Kvalsvig says.

“What ventilation is doing is getting in the way of that process. It’s much more directly preventing transmission than a lot of the other control measures we use. And that’s good news because you also avoid a lot of the adverse effects of those control measures.

“That’s the everyday life that we want. We want to be able to be connected and be in contact but not transmit. That’s what we should be going for, the gold standard of pandemic control.”

Then there’s the other benefit from ventilation – it’s much more passive than relying on everyone to wear a mask, in the right way, at the right time.

“What I’ve seen in the public debate is a lot of focus on masking and getting individuals to comply with masking. Masking is actually very difficult,” Russell says.

“You need a lot of individuals complying, you need masks that are tightly fitted, you need triple layer masks to actually reach the level that’s helpful. But when we improve ventilation, that doesn’t involve every individual complying but it will lower the risk of transmission for all of the children in the classrooms.”

The first step to cleaner air

How do we actually do that?

Air quality is a complex, technical issue and it’s also highly dependent on individual buildings and rooms.

“For any building, ideally you’d want to be able to assess that individual building, because buildings are so different. And then to remedy what the problems might be,” Kvalsvig says.

The focus for officials in the immediate future will be schools, where students in Auckland who can’t be vaccinated will soon be returning.

“There have been studies which show that ventilation in New Zealand classrooms doesn’t meet the expected standards for up to half the day,” Russell says. “There’s a general sense that we don’t have a great track record on ventilation in classrooms.”

Most schools in New Zealand rely on natural ventilation – opening the windows.

“You’re looking for cross ventilation. We’re lucky in that way that a lot of the classrooms in New Zealand rely on natural ventilation. Often classrooms have windows on both sides, up high, so you can get a good proper flow,” Bennett says.

For those classrooms where natural ventilation isn’t possible or doesn’t do enough, Russell says we should look to limit the number of people in the room and the time spent in it.

A range of low-cost tools are also available to assist with ventilation in this first stage of the transition to taking air quality more seriously. Carbon dioxide monitors, which are being distributed to schools, serve as a proxy for rebreathing. The higher the CO2 levels, the more exhaled air is in the room.

“It’s more of an indicator, it can give an idea of when people need to take action. If the levels are getting too high, the windows might need to be opened or the class might need to move outside to let the air exchange happen,” Bennett says.

The state of Victoria, in Australia, has also purchased a large number of portable air purifiers with “high efficiency particulate air” (HEPA) filters for use in classrooms. Rather than ventilate the room, these devices filter most viral particles out of the same air, making it safe to rebreathe.

Even those schools which do have natural ventilation resources will still struggle when next year’s winter rolls around and opening the windows is no longer an option. At that stage, Covid-19 is likely to be in the community nationwide, though hopefully in low numbers. The vaccine rollout for five-11s may well have started, but at least some will still be unvaccinated. Air purifiers might be a crucial tool to keep schools open in the winter of 2022.

In New Zealand, education and health officials have provided guidance on natural ventilation and are working with NIWA air quality experts to monitor CO2 levels in classrooms. But Covid-19 Response Minister Chris Hipkins says he doesn’t think there’s a case for placing an air purifier in every room, at least while summer weather means opening the windows is a cheap and accessible alternative.

The air quality overhaul

As useful as air purifiers, HEPA filters and carbon dioxide monitors may be, they’re really just ad hoc starting points in experts’ ideal journey to treating air quality as a crucial public health measure.

That quest envisions a much more total overhaul of building regulations – and of the infrastructure of existing buildings. It goes beyond schools, targeting all of the places people spend long hours in close contact with one another.

“Schools are a good example of where we need some pragmatic starting points. But at some point that must transition into long-term solutions, because the pragmatic things don’t work as well as the enduring ones,” Kvalsvig says.

“It’s got to be evidence-informed. And then the next thing is the resourcing, because that’s the biggest barrier. That’s why there’s been such a lot of pushback about this idea of ventilation, because it then puts the responsibility on government to resource what needs to happen.”

Bennett is ready to rattle off a wish list when asked to dream big.

“It really needs a comprehensive approach. Long term, we need to be changing building codes, we need to be considering indoor air quality standards in any kind of buildings, we need building upgrades. That is going to be a big investment,” she says.

“We’ve seen in the MIQ facilities that hotel rooms aren’t necessarily suitable for having people who are infectious in them. They’re not designed for the ventilation and things. It goes for all buildings that we need to be really considering what kind of systems we’re going to be putting in these buildings and how are we going to keep them warm. That might take us to a different way of building and a higher set of standards to get the outcomes that we’re after.”

Bennett says this is an endeavour that will take decades, but it will be worthwhile.

“I would hope that thought is going into, what can we do in the future to ensure that if we have another pandemic, that we’ve thought about these things and we’re preparing for these things and our buildings are going to help us through these things.”

Kvalsvig isn’t optimistic these changes will come through. “It’s who’s going to take ownership of this problem is the first step, and it’s always the difficult step. What I’m worried about is that it’s going to devolve onto individuals,” she says.

“You could take a CO2 monitor into your workplace and say, ‘This is not good enough’. But then all the burden is on you, the less powerful person, to persuade the more powerful people to do something about it.

“I hope I’m wrong, but my prediction is we’re going to start seeing schools fundraising for CO2 monitors and HEPA filters to improve the quality of their classroom air. Schools in high-income areas will be able to do that very effectively and schools in low-income areas won’t be able to.”

‘Enduring legacy of the pandemic’

If Government and employers do step up, the benefits could be enormous.

This approach won’t just help tackle Covid-19. It could have a huge impact on other public health challenges and even on student performance and worker productivity.

Researchers have repeatedly found that improving indoor air quality in offices increases the cognitive functioning of employees, reduces headaches and improves worker health. People are less likely to get sick, meaning they’re less likely to need time off or to show up to work unwell. The cost of the latter phenomenon was estimated by one Australian insurance company as costing the country AUD$34 billion, or 2.7 percent of GDP. Sick days only add further to that cost.

Students taking exams in rooms with lower air quality were found by one UK researcher to have lower exam scores, compared to their peers. The installation of air filters in Los Angeles classrooms in 2016 was found to boost student performance as well, to a degree similar to the increase expected from reducing class sizes.

Then there are the health benefits.

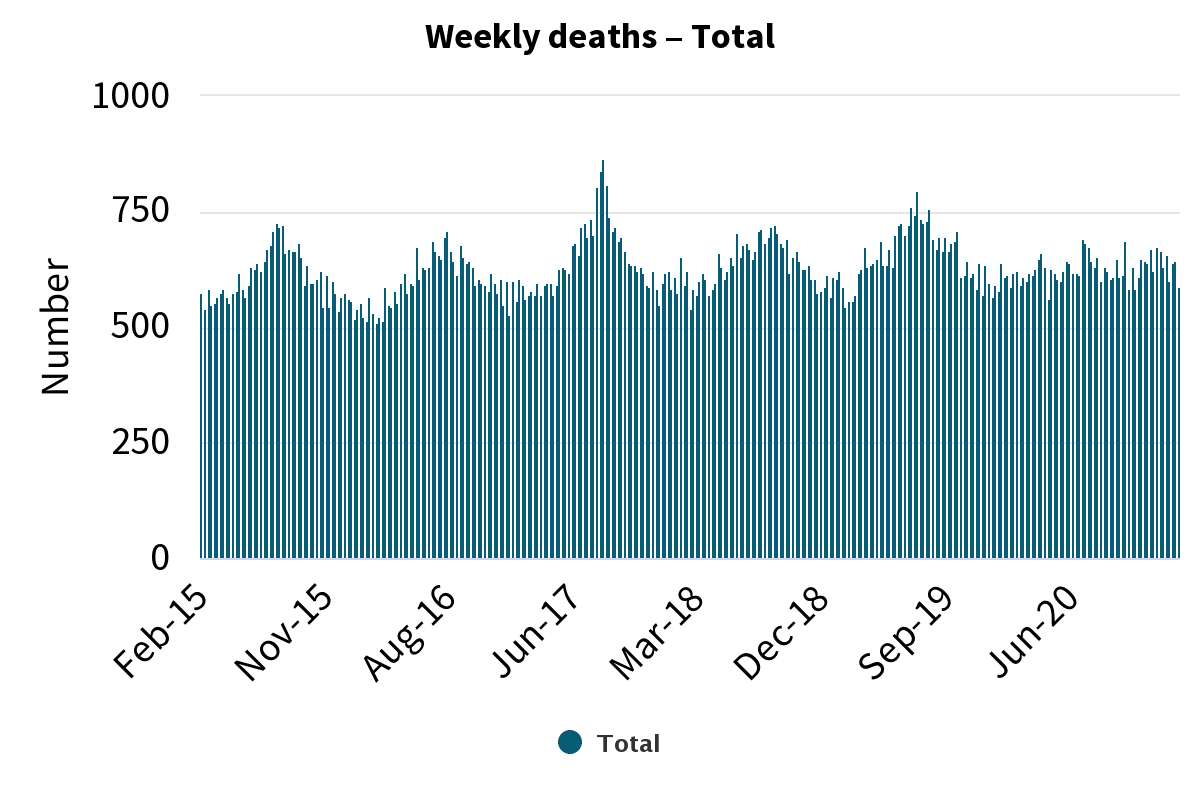

Every winter, deaths in New Zealand spike by about a third. But New Zealand’s Covid-19 measures eliminated that winter disease burden in 2020 and severely reduced it in 2021.

Obviously, we don’t want to lock the country down every autumn. Ventilation is therefore an opportunity to build in an enduring disease control measure that doesn’t significantly disrupt people’s lives.

“This is a great public health measure because it doesn’t just protect against this virus, but a whole raft of other infections,” Kvalsvig says.

“We could lose that winter respiratory burden. It does include deaths, but a huge iceberg below that of illness, some of which is quite serious. A good example of that is RSV. I would like to see 2020 be the watershed year when all of that changes.

“So we don’t have hospitals full every winter, we don’t have people off school and work. We seem to expect a whole lot of illness each winter. And now we know it’s preventable. We can’t un-know that.”

Bennett agrees, saying ventilation could have a huge impact on the winter burden.

“All infectious diseases that are spread through the air, it’s going to be improved through better ventilation. It’s a shame that a pandemic has had to highlight this issue. It’s an issue that I’ve been passionate about for a long time and I’ve found it very difficult to get anyone to listen to me about indoor air quality.”

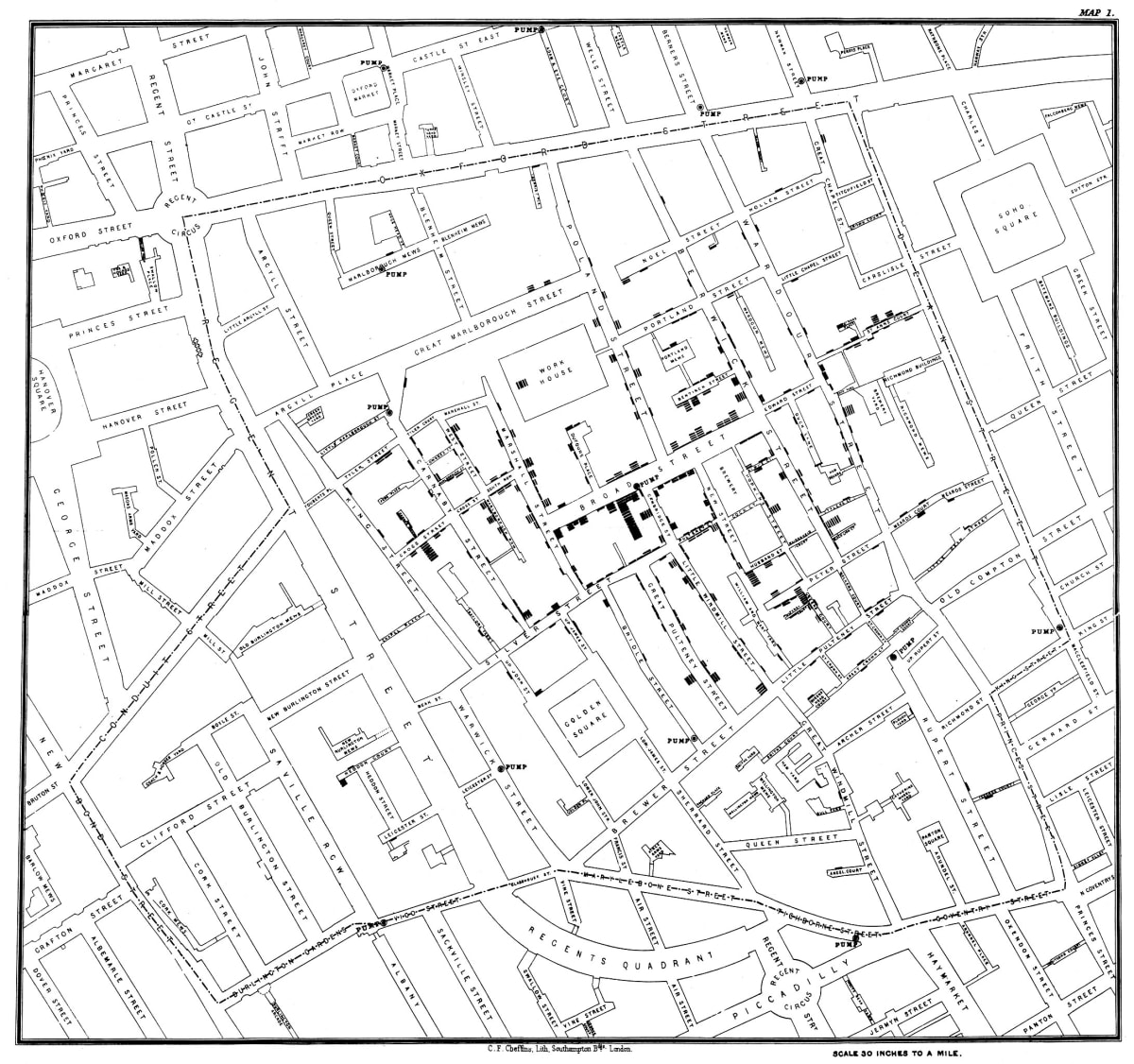

Kvalsvig thinks back to one of the founding events in the study of epidemiology, as a blueprint for the significance that improving air quality could achieve.

In 1854, physician John Snow found that an outbreak of cholera in Soho – part of a broader epidemic which killed 10,000 Londoners in two years – was clustered around a single public well. The water which fed into the well came from the city’s sewage systems, leading to contamination and illness.

Snow pushed the local officials to disable the pump, which they ultimately did. The outbreak in Soho waned.

Eventually, new sewage systems separated out human waste from drinking water. London never saw another cholera outbreak after the new system came online.

“I’ve been thinking about [ventilation] very much in a similar way,” Kvalsvig says.

“In London, they really fixed waterborne transmission by fixing their wastewater systems. They just fixed it. It’s incredible to think about cholera outbreaks in London being commonplace, happening all the time.

“What we need is that transformation, but for air. This should be the enduring legacy of the pandemic.”