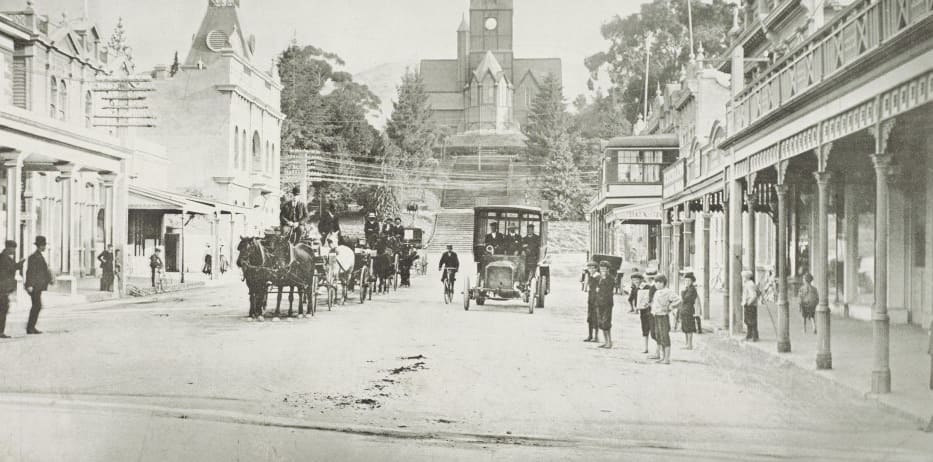

Comment: Back in the day, when the first motor vehicles arrived and scared the horses, people wondered why you would want one of those expensive, noisy, smelly things. As there were no fuel stations or garages back then, they also worried where you’d get the fuel from, and how you’d get it fixed. After all, the horse was quiet, ate the grass in the paddock behind the house, and the owner knew how to fix it.

Climate change requires us to make another step change to our transport systems. And yes, this is daunting, just as it was last time, when we shifted from horses to fossil fuelled vehicles.

Now, we must step away from our fossil fuel burning, carbon-emitting vehicles and adopt a new range of ‘future’ fuelled transport options that are close to carbon-zero (nothing is ever perfectly zero) or are at least carbon-neutral (recycle their carbon). Which future fuel is best will depend on the particular situation being considered.

After walking or cycling (active transport), the best carbon-zero emission transport option is an electric motor driven by direct electrification i.e. plugging it into the renewable electricity supply. This is already commonly used in trams, trains and trolley buses with overhead lines or an electrified rail.

When direct electrification is not possible, a range of future fuels, which store the renewable electricity for use later, can be considered, including batteries and green hydrogen (carbon-zero), or bio-fuels and syn-fuels (carbon-neutral). Common to all of them is that they require renewable electricity to charge or form them, and the energy stored by them is less than the electricity used to charge or form them.

For light vehicles on short trips, the best future fuel is that supplied to electric motors by batteries (which are charged by renewable electricity and carbon-zero) such as EV cars for driving around town, and light short-haul planes.

But for heavier transport on longer trips – heavy trucks, coaches, trains, medium haul planes – the best future fuel is green hydrogen, made from water by electrolysers driven by renewable electricity (carbon-zero). When burnt in a fuel cell it produces only water and electricity to drive the electric motor – there are no carbon emissions.

Both batteries and green hydrogen require the roll out of a network of recharging and refuelling stations – a step change like that made when we moved from horse to fossil fuels. To address climate change, this step change must be made, as both are carbon-zero future fuels.

Finally, there are some situations where the carbon-zero future fuel options – either the best option of direct electrification, or the next best options of battery/hydrogen – will not work. For example, in very long distance (long haul planes) or particularly heavy transport situations (freight ships), a liquid fuel may be still be required, such as a bio-fuel or syn-fuel.

Biofuels are made from biological materials such as wood, whilst synthetic fuels can be made from captured carbon dioxide. It is important to note that both require green hydrogen in their production.

These are ‘drop in’ future fuels, meaning they can be used in existing combustion engines, with some small tweaks, and distributed and stored in the same ways as present fossil fuels. This is clearly a huge advantage. However, when burnt, these emit carbon, so the best they can be is close to carbon-neutral fuels and that requires careful book-keeping, as the carbon must be recycled back from the atmosphere when those future fuels are made.

Ammonia is the key precursor to nitrogen-based fertilisers and is another potential syn-fuel – one that contains no carbon. Again, green hydrogen is required for its production. It is important to note that hydrogen is also a key enabling industrial chemical, as well as being a fuel.

We know we cannot keep using fossil fuels, as they are killing the planet. Hence we must be brave and rapidly make the step change to these future fuels, thereby dramatically cutting back on the 60 percent of New Zealand’s total primary energy supply being provided by fossil fuels.

To do so requires us to about triple our renewable electricity generation. New Zealand has the wind, sun and water to do this. Where possible, this green electricity should be used as it’s made, but we will also need to store some of it in each of these types of future fuels.

Which future fuel will be best will depend on the particular system being decarbonised, but we are extremely fortunate to have the natural resources to lead the world in making this critical step change towards a more sustainable future.