*This story was first published on November 2, 2021*

Canterbury’s oft-criticised water regulator, ECan, is being accused of hiding a damning report which makes allegations against a listed power company and a giant irrigator.

The regional council’s report centres on water stored at Lake Coleridge, operated by NZX-listed Trustpower, and released down the Rakaia River to irrigators – the biggest of which is Central Plains Water.

Report author Wilco Terink, a senior hydrological scientist and data analyst, who worked on the project since its inception in April 2018, resigned from the regional council earlier this year.

In recent weeks, ECan has given copies of what it calls “the draft report” to select parties in response to official information requests. What it has actually released is a sanitised version with many sections removed, including the executive summary, conclusions and recommendations.

The original report – a copy of which has been leaked to Newsroom – makes startling claims.

Dated May 2021, the report says there is evidence the Rakaia’s water conservation order is being breached and consent limits for water-takes are occasionally being exceeded.

The river is being “impeded and manipulated” beyond what was anticipated in the water conservation order – a legal instrument, setting strict management conditions for the Rakaia, described by environmentalists as being like a national park for rivers.

Breaches of the order (WCO) would likely be a national issue.

A spokesman for Environment Minister David Parker said: “ECan has not briefed Minister Parker about any potential breaches of the WCO but he has been made aware of the existence of the draft report. The Minister has not received any application to change the WCO and is not considering an amendment.”

“ECan has failed the people of New Zealand.” – Paul Hodgson

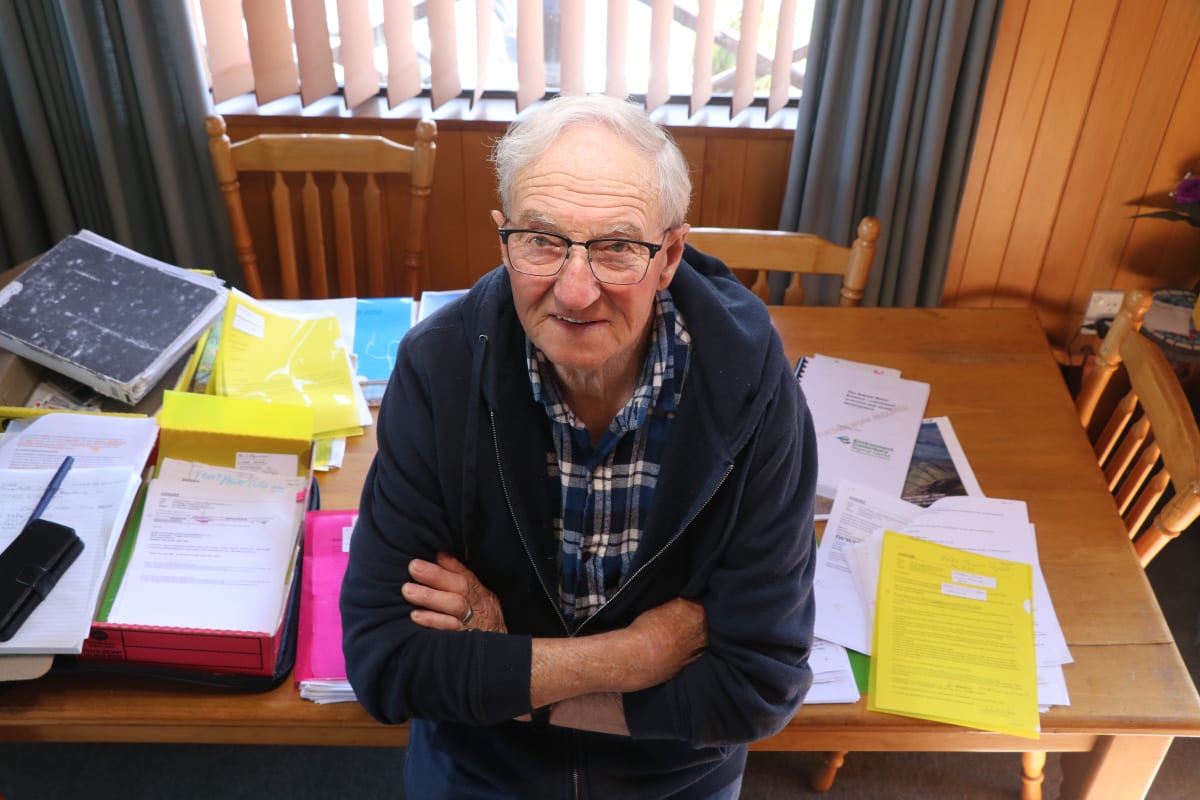

Bill Southward, of Rakaia Huts, is one of the river’s biggest advocates. His voluntary work, including personally paying for river gauging cross-sections, was recognised in 2013 when he received the Coastal Society’s inaugural national coastal champion award.

The 77-year-old believes ECan is covering up the report. “What they found out they didn’t like.”

Paul Hodgson, of Christchurch, is a committee member of the NZ Salmon Anglers Association. He’s fished the Rakaia for 50 years and has watched as it was diminished from a powerful river to one that’s wadeable all the way across. “Thirty years ago you couldn’t do that.”

For years, anglers have been telling ECan too much water is being taken from the Rakaia.

“The river that I knew is gone,” Hodgson says. “The birds aren’t there, the insects aren’t there, the weeds are there. There’s no joy in it. It’s gone.”

He adds: “ECan has failed the people of New Zealand.”

Peter Trolove, president of advocacy group Federation of Freshwater Anglers, posted a copy of the sanitised report on its website last week. He said since the WCO was amended the recreational and native fisheries had collapsed in the lower Rakaia River.

ECan’s emailed response to Newsroom’s questions came from surface water science manager Helen Shaw, who manages the Rakaia project. Terink’s report was reviewed internally and externally in October last year yet it hasn’t been published. Shaw says ECan has not sat on it for the last year.

“The report is not yet final and ready for release, and the project is not complete,” she said. “We released the draft report to selected parties in response to official information requests. When the report is complete and passes peer review, a final version will be uploaded to our website.”

In the past, ECan has shown itself to be a permissive regulator which has been reluctant to enforce consent conditions. Of course, the Rakaia isn’t the only river it manages.

Greenpeace Aotearoa’s senior agricultural campaigner Christine Rose says it always warned Central Plains would be bad for the environment, and Terink’s report “proves the point”.

“Increased water extraction is bad for the lake and bad for the river, and by facilitating intensive dairy, it’s bad for people’s drinking water, downstream freshwater quality and the climate.

“Just like synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, big irrigation schemes are the lifeblood of the highly polluting intensive dairy industry.”

Some of the most damning passages in Terink’s original report relate to the regulator itself.

It’s revealed that in 2014, ECan – through law firm Wynn Williams – advised Trustpower to seek an Environment Court declaration to ensure its new operating regime for Lake Coleridge was consistent with the water conservation order.

Trustpower, which operates a hydroelectric power scheme at the lake, went ahead and implemented the regime, known as warehouse stored water, without seeking a declaration.

(By deciding to “store” water below the lake’s operating range the “theoretical storage capacity” expanded more than three times, to more than 300 million cubic metres. Trustpower told ECan there would be no additional environmental effects and the lake would stay within its consented operating range. However, the Terink report says on 10 occasions in 2015 there was “illegal creation” of stored water.)

Snubbed by Trustpower, ECan didn’t act – even to check if the regime was consistent with the WCO. That was left to Terink. His report, written more than six years later, says this has “raised concerns regarding compliance”.

“It can be concluded that calculations behind this concept do not meet the conditions set out in the [WCO] amendment,” the report said. Another discovery was a “substantial” increase in diverted water into Lake Coleridge from the Wilberforce River, which potentially breached the consented limit. (Because of the configuration of Coleridge’s canals, diversions from the Harper and Wilberforce rivers are difficult to monitor, so remote sensing – imagery from satellites or planes – was used to check.)

Similarly, in 2015 Central Plains Water was allowed to adopt an “alternative strategy” for taking water, calling on so-called subservient water not being used by other consent holders. (Water-take consents are governed by an overly complex tangle of 25 so-called “flow bands”. Basically, the older your consent the more reliable your supply.)

Terink’s report said it was shown the company “exceeds its consented rates”. Again, this analysis was only completed years after the strategy was implemented.

It was a major concern ECan wasn’t able to monitor Central Plains’ consent effectively, the report said.

(The irrigation company wrote to ECan in 2015 thanking the council for confirmation its “proposed averaging approach” for taking subservient water was acceptable. However, the Rakaia report said ECan had no evidence it accepted such an approach.)

ECan has effectively been flying blind. It doesn’t know how, at any given moment, how much water is entering Lake Coleridge, or the lake’s level, or how much water is flowing from the lake, the Rakaia report says.

The council is shut out of real-time water meter data, and the metering data is poor. Checking consent compliance is “very difficult if not impossible”.

A major impetus for studying the Rakaia was complaints, made over many years, from river users, like fishers, jetboaters and kayakers, about low flows and water levels, despite the supposed protection of the conservation order.

Since the order was amended, the Rakaia report notes “irrigators have reported that flows have become more unreliable”.

Rakaia water report highlights by David Williams

Newsroom put to ECan the Rakaia report contains embarrassing information about the regulator which it might want to keep from public view; and not publishing it could be seen as a cover-up.

Surface water science manager Shaw says the report has been changed several times, “which is common”. Several sections were removed from the report’s fourth version – including any mention of ECan advising Trustpower to seek an Environment Court declaration. Those details aren’t relevant to a report focused on model development, she says.

During the report’s review, it was recommended ECan focus on the model build, she says – “the Rakaia water balance report is not a compliance report”.

However, that defies its stated purpose.

Newsroom has obtained a copy of the project plan from April 2018, which said the model would help understand the river’s natural behaviour. What it would also do is help evaluate whether “consent holders are complying with their consents”, and “the Rakaia River is properly managed according to the WCO and consent conditions”.

The ECan manager who approved the plan was Helen Shaw.

(One of the listed consequences of not pursuing the project was reputational – “ECan needs to be able to share data and findings with our community”.)

Shaw says when the model is “verified and updated” it can be used to “better test compliance” with consent conditions and the water conservation order.

Updating Terink’s report makes sense, given the analysed data spans only from 2003 to 2017. Shaw maintains ECan will take enforcement action if breaches are found.

“There is a statute of limitations that only allows us to take action within 12 months of when we should have reasonably become aware an offence took place. Data analysed in the current draft report is now several years old; we cannot take enforcement action in response to old data. We are looking to update the model with more recent data.”

Shaw says the regional council has met large consent holders like Trustpower and irrigation companies regularly, as part of ongoing compliance monitoring, “to ensure they understand their obligations and abide by consent conditions and other restrictions”.

Questions sent to Trustpower and Central Plains Water included: how can compliance with consents and the water conservation order be verified when there aren’t flow recorders on all takes or diversions?

Trustpower’s general manager of generation Stephen Fraser said, in full: “Trustpower has received a copy of the draft report from Environment Canterbury, which requires further work to ensure accurate and complete data modelling. We are working with Environment Canterbury to provide the information and data needed to inform a complete report. All of our consented water takes are measured, and we are confident that our operations are compliant with our resource consent conditions.”

Central Plains confirmed it had received a copy of ECan’s “draft” report.

“It is substantial and on completion, will provide a valuable resource,” chief executive Mark Pizey said in an emailed statement. “However, there is further work to be completed on this draft to ensure the data modelling is accurate. CPWL will work in conjunction with Environment Canterbury to ensure accurate data is used in the further modelling to support the final report.”

News of Trustpower’s controversial plan to provide Lake Coleridge water to irrigators came to light in 2009 .

The company revealed details two years later, saying it wanted to “bank” water in Lake Coleridge and “compliant” water shouldn’t be subject to the water conservation order’s flow-sharing regime. Fish & Game called that “gobbledygook”.

In 2013, the order was amended by the Government – on ECan’s recommendation – allowing Trustpower to release the lake’s water for use by irrigators. At the time, Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Minister Gerry Brownlee praised ECan for its balance, saying it was a good example of taking into account both environmental and farming community needs.

However, the suppressed Rakaia report casts doubt on ECan’s management. The council has little access to real-time monitoring data, and appears reluctant to publicise the findings of potential breaches.

Terink’s original 276-page report shows the Rakaia is a complex river. Modelling it is also complex, factoring in rain, snow melt, evaporation and losses from the river to groundwater.

The report concludes the river’s flow at the mouth is periodically “well below” the monthly minimum.

ECan’s Shaw says because the Rakaia is braided, flows at the mouth can’t be continuously monitored.

“Our intention is to use the model, along with measured water use data from consent holders, to estimate the flows at the mouth at any point in time. This will mean that we are able to assess whether the objectives of the WCO are being met at the mouth of the river, as well as at the gorge, where flow is monitored.”

Up to 70 cubic metres per second can be abstracted from the Rakaia in what’s called “one-for-one” sharing. If the river is running 40 cumecs above the minimum flow, for example, 20 cumecs could be taken and the equivalent amount would be left for the river.

In the hearings for Trustpower’s proposed variation to the water conservation order, it was said flows in and out of Lake Coleridge would have to be carefully monitored and recorded. ECan told independent commissioners “a rigorous monitoring and web-based management regime based on virtual gorge flows can be developed with Trustpower”.

Trustpower does monitor the lake. But Terink’s original Rakaia report recommended the council install its own flow recorders at Lake Coleridge so the water regulator has direct access to the data.

ECan councillor John Sunckell owns a 600-cow dairy farm at Leeston, 40km south-west of Christchurch. He tells Newsroom he has read the Rakaia report’s executive summary – which is redacted from the sanitised version – but councillors are yet to discuss it formally because it’s still a draft.

Asked about low flows in the Rakaia, Sunckell says: “I’m not really aware of any great conversation that’s happening out in the wider community, particularly in the agricultural space.”

The councillor says ECan takes compliance with water consents seriously. The Rakaia report, once out, will give the council “something to look at and reassess”, he says.

Sunckell says his farm has three groundwater wells under one consent, and another consent for a well on a support block. All wells have data recorders which send information by telemetry, to ensure daily and annual volume limits are complied with.

An external firm provides an audited annual report, and every five years the equipment is physically checked.

“There’s no way of circumventing the system,” he says. “No, we don’t have ECan coming on farm, but everything’s electronic – we can’t bloody hide from it.”

Surface water science manager Shaw says: “Consent holders supplying information on their consent compliance for checking by compliance officers is common, cost-efficient to ratepayers, and effective.”

A finalised – and heavily modified, presumably – copy of Terink’s report may not be made public by ECan for some time.

The “draft model report”, as Shaw calls it, was released to stakeholders and some selected groups to “verify that it is producing sensible/realistic results”.

“Once we have confidence in the model (informed by feedback), we will need to incorporate more recent data. This is not a fast process, but is part of our long term budget.

“We estimate that it will take another six-to-12 months to collate feedback from all parties, and update the model.”

That is at least four years since the project started.

“They give out these consents, they’ve got to check that it’s actually happening.” – Bill Southward

For years there have been warnings – including from the regional council – about the environmental damage caused by intensive farming in Canterbury.

In 2002, a report by an ECan groundwater scientist warned the effects of land surface activities on groundwater nitrate concentrations was being clearly demonstrated by data. “They indicate that without proper management the intensification of agricultural land uses in Canterbury could pose a significant threat to groundwater quality.”

That turned out to be prescient.

The regional council’s latest annual groundwater survey found nitrate-nitrogen concentrations were likely or very likely increasing in 47 percent of monitored wells.

In the preceding decades, Canterbury, an irrigation powerhouse, experienced a 200 percent increase in irrigated land, and an almost 10-fold increase in dairy cattle, to 1.3 million, and a significant increase in the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers.

Last year’s Our Freshwater report, by Ministry for the Environment and StatsNZ, noted rivers in parts of Canterbury had worsening trends for nitrate-nitrogen, E.coli, and turbidity.

Changes to the intensity of farming in Canterbury coincided with a tumultuous time for ECan, as the Government sacked the regional councillors and replaced them with appointed commissioners. At the same time, former prime minister John Key’s administration pumped millions of dollars into pro-irrigation policies.

Southward, the river advocate who lives at Rakaia Huts, has been pressing ECan for information about TrustPower’s Lake Coleridge project for years.

He shows Newsroom emails from 2017 asking for flow data to ensure the water conservation order is being complied with. “They give out these consents, they’ve got to check that it’s actually happening,” he says.

He was delighted when ECan decided to study the Rakaia. Now he’s left tired and disillusioned.

“It’s just worn me out, and other people I know they feel just the same way. I’ve devoted my life to it – I’ve got 12 banana boxes full of stuff.”

But he can’t just walk away when there are so many unanswered questions. Where have the smelt gone? Why are the birds dying? And now, why hasn’t ECan published the Rakaia report?

“The media’s the only way they’ll do anything,” Southward says. “You’ve got to shame them.”

* This story has been corrected. Previously it said Environment Minister David Parker was concerned about the leaked ECan report but that was the result of a miscommunication with his office.