The Climate Change Commission’s draft recommendations to government on our response to the climate crisis is extensive and helpful. But the quality of its work varies widely. Its best is on the climate crisis itself and how government must improve its climate policy development, co-ordination and delivery; and its worst is on what some of those policies should be.

The weakness stems from the Commission’s narrow view. It focuses mainly on near-term actions and policies which it believes are, or soon will be, practical, deliverable and affordable. To the limited extent it has a sense of the future, it looks largely similar to now but with lower emissions.

However, the future will be very different. Dramatic human-induced shifts in the climate and Earth systems will force on us make big changes in our values, priorities, technologies, and economic, financial and business systems. What we do and how we do it will be very different in 30 years’ time.

If we spend the next 15 years executing the Commission’s strategy of partially decarbonising existing systems with largely existing technologies, we’ll be blindsided by the radical changes that will happen anyway in the following 15 years.

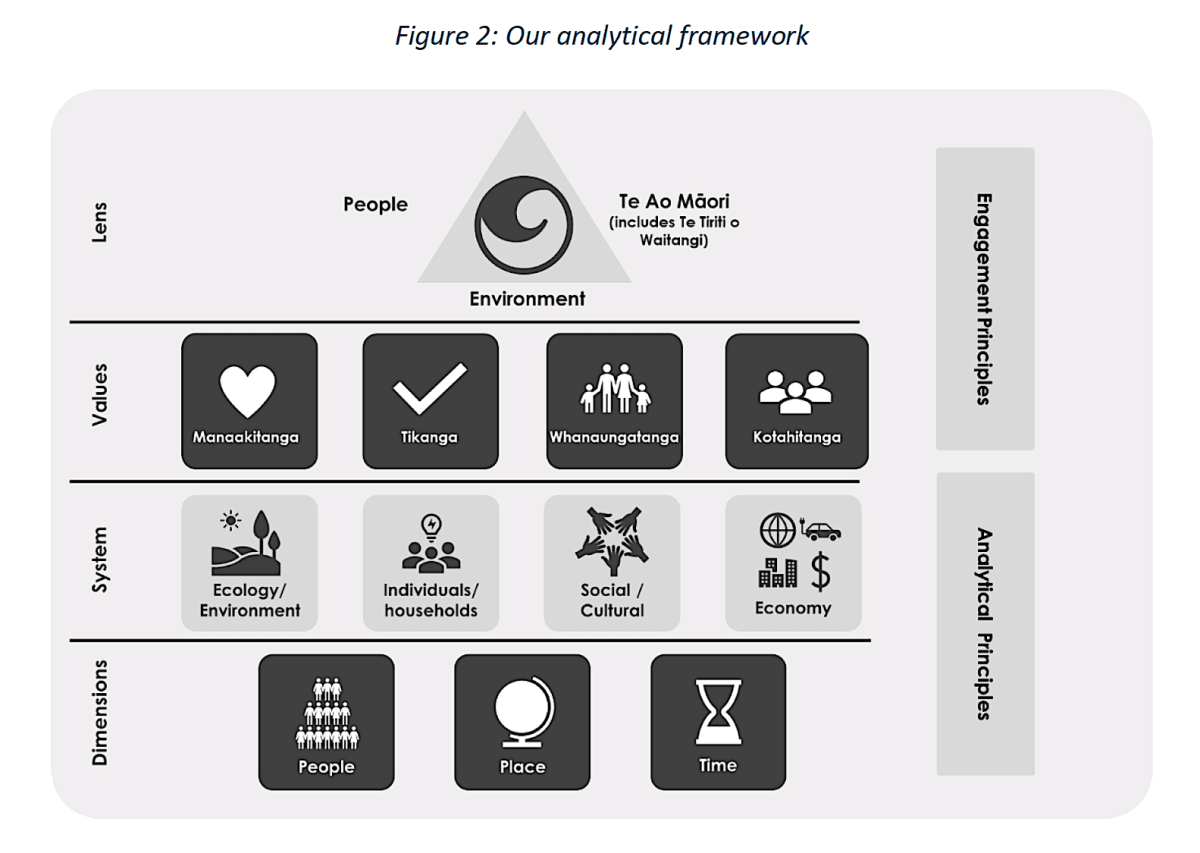

This chart below of the Commission’s analytical framework best explains the trap the Commission has set itself, and thus the country. It comes from the Commission’s 17-chapter, 650-page evidence report that underpins its 180-page draft advice to government on New Zealand’s budgets for carbon emissions over the next 15 years and the pathways it believes we should follow to reduce those emissions.

The three lenses in it are appropriate but they are barely explored; likewise the four human values and responses that flow from them.

The real problems start, though, with the four systems. The ecology / environment one makes no attempt to assess how dramatically we humans are degrading Earth systems and thus their ability to support all life on the planet, human and non-human; the economic one, as the Commission describes it, is remarkably conventional so its analysis provides few and vague answers; and the individuals / households and social / cultural systems are likewise superficially described and assumed to be largely unchanging.

Meanwhile, there is ground-breaking work to be found elsewhere. The UK Treasury, for example, has just released a 600-page report on the economic importance of nature. Human prosperity has come at a “devastating cost” to the ecosystems that supply us food, water, air and other natural resources, says its author, Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta, a Cambridge University economist.

Or, as UN Secretary-General António Guterres said in December: “Humanity is waging war on nature. This is suicidal. Nature always strikes back –and it is already doing so with growing force and fury. Biodiversity is collapsing. One million species are at risk of extinction. Ecosystems are disappearing before our eyes … Human activities are at the root of our descent toward chaos. But that means human action can help to solve it.”

If you have any doubt about the extensive damage we’re doing to our ecosystems in New Zealand, read the Environment Aotearoa 2019 report and A Safe Operating Space for New Zealand/Aotearoa. The latter is recently released analysis of New Zealand’s breach of most of the planetary boundaries. Both reports were published by our Ministry for the Environment.

Such global and local analysis has a fundamental principle at their heart: our response to the climate crisis we’ve caused goes far beyond simply reducing carbon emissions in the hope of forestalling the rise in global temperature. Where at all possible, every action we take must also contribute to helping nature – our life-support system – recover its diversity, vitality and resilience.

Back in 2006, the UK Treasury released a report on the economics of climate change it commissioned from Nicholas Stern, another distinguished British economist. His core message was that the urgent and essential economic investment we had to make to respond to the climate crisis was highly affordable and would deliver multiple benefits. Moreover, acting promptly would prevent some irreversible damage and reduce the costs of acting later. Despite fierce opposition from many quarters, his seminal work transformed economic understanding of the climate crisis.

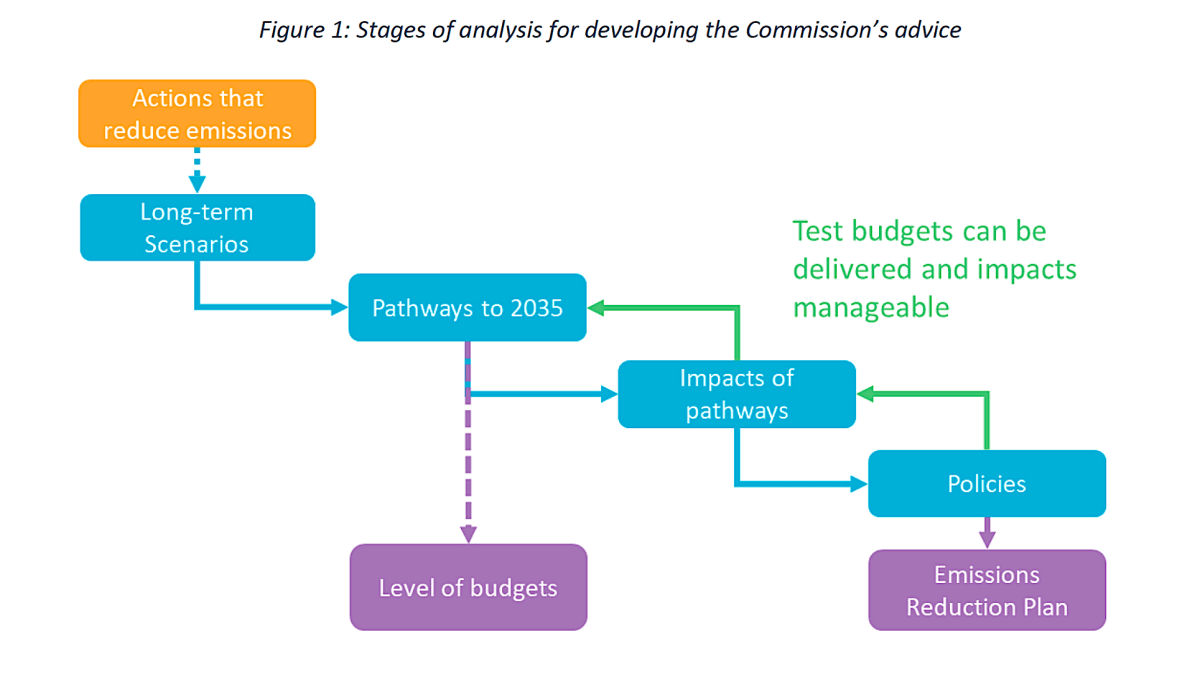

However, our Climate Commission pays insufficient attention to this economic revolution. Likewise it fails to deal with big shifts underway in technology, values and other core drivers. As a result, it has artificially limited its range of actions, which then compromises every stage in its analytical approach, which it describes in this chart:

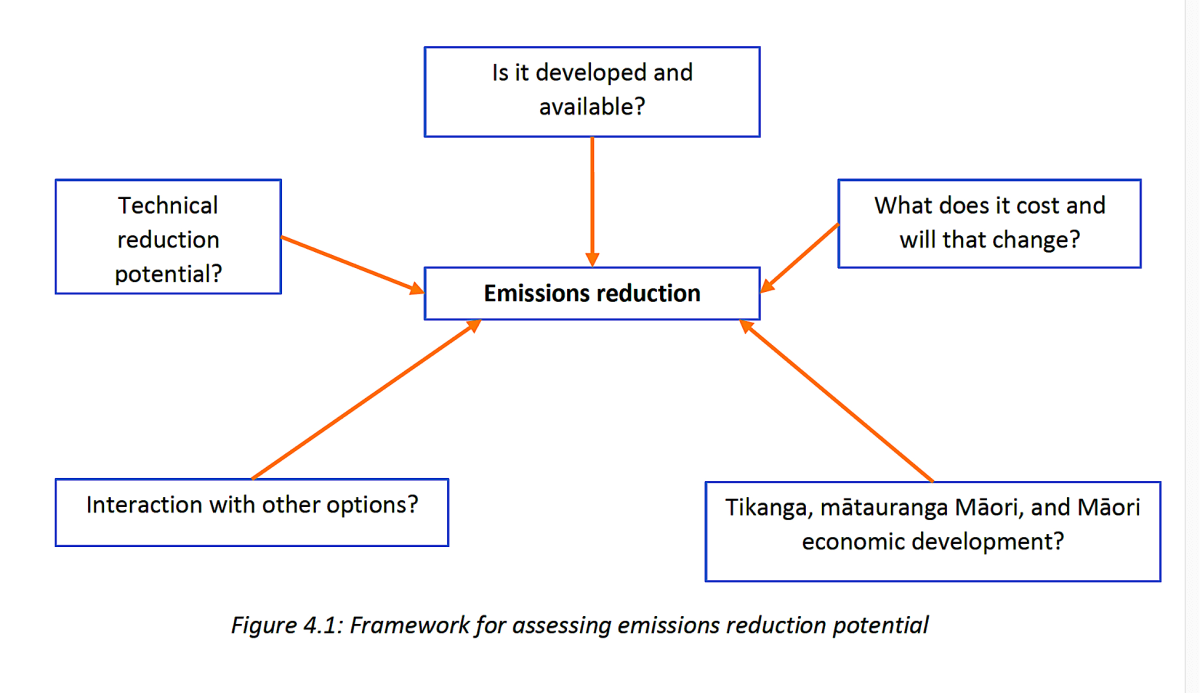

In the final stage of its analysis, it applied the decision matrix it charts below to come up with its draft recommendations for our carbon budgets and emission reduction pathways and policies.

Note the emphasis on whether a potential method of reduction is developed and available. It takes this weakness to an extreme in the case of agriculture. Its entire suite of recommendations for the next 15 years are all current technology and practices being used by some farmers. Thus the goal is only to make them common across the sector to make a modest reduction in their emissions; not to play our unique role in fast-forwarding the food revolution.

Tinkering with existing systems is absolutely not the future of farming and food here or around the world over the next 15 years. I most recently described the farming and food future humanity needs in this Newsroom column last May. And I’ve developed the themes much further in a chapter on New Zealand agriculture which I’ve contributed to Climate Aotearoa: What’s happening and what we can do about it. This is a collection of essays edited by Helen Clark, which Allen & Unwin is publishing in late-April.

Yet, despite all these short-comings the Climate Commission’s draft report does layout many compelling and coherent recommendations of what we must get underway in the near term. But in advocating such an approach, the report reads as though it was written for one person in particular and a handful of her colleagues: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and ministers with climate responsibilities, particularly James Shaw, Grant Robertson, Megan Woods, Damien O’Connor, Michael Wood and David Parker.

Indeed, their response was encouraging. But they still have show they can get the Government’s act together on climate over the rest of this year. If they can, then they might start to lay the ground work for the greater ambitions and bigger changes required urgently thereafter.

But to help them lift their game, the Commission has to up its performance with its final recommendations to the Government in May. Many knowledgeable, committed people around the country can help by making submissions to the Commission by its deadline of March 14, details here.

This is my view on each of the 17 chapters in the Commission’s evidence report, highlighting where the Commissioners and their staff particularly need far more input, new thinking, rigour and ambition:

– Excellent: Chapter 1 on the science of climate change; 7 on where we are currently heading; and 10 on our UN commitment.

– Good: Chapter 3 on how to measure progress; 6 on Maori perspectives; 16 on our approach to policy; and 17 on the direction of policy for Aotearoa.

– Adequate: Chapter 4 on emissions reduction opportunities and challenges across sectors is OK only on heat, industry and power; and Chapter 5 on removing carbon from the atmosphere.

– Disappointing: Sections of Chapter 4 on transport, particularly on active transport; Chapter 8 on what our future looks like; 9 on which path we should take; and 13 on households and communities.

– Bad: Sections of Chapter 4 on buildings and urban form; and grievously so on agriculture; 2 on what other countries are doing; 11 on what could this transition to a low emissions economy and society mean for New Zealanders (astonishingly, just 1½ pages plus two individual references); 12 on how we earn our living (this is the economic analysis); 14 on environment and ecology; and 15 on the link between mitigation and adaptation (astonishingly, only 2½ pages plus two pages of references).

So, let’s give the Climate Commission all the support it deserves to turn a good draft report into an outstanding final report – one which will inspire us all to rise to the towering challenges of the climate crisis and to make the most of the transformational opportunities those give us.