From Vienna to Wellington: A migrant’s story

ANALYSIS: Inge Woolf escaped the Holocaust to become a pillar of the capital’s community.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

ANALYSIS: Inge Woolf escaped the Holocaust to become a pillar of the capital’s community.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

If diversity and inclusion can claim superiority over their monocultural alternative, the evidence lies in the great European imperial capitals of the 19th and 20th centuries.

One of them, Vienna, was the most multicultural in Europe. It was the home of the dual monarchy of Austria and Hungary, where 50 million people of nine major nationalities and numerous minorities resided.

The definitive book on Vienna’s golden years.

As former Newsweek journalist, Andrew Nagorski, put in one of his books on central Europe: “The Habsburg rulers granted diverse subjects and regions limited yet impressive autonomy, allowing them to set many of their own rules while trading and travelling.”

Not surprisingly, this was a “recipe for political and economic success” that rested on a built-in willingness “to tolerate the ambiguities, contradictions, and tension inherent in such a relatively enlightened multinational, multicultural arrangement”.

By the end of the 19th century – the fin-de-siècle – Vienna’s golden years denoted it as the Continent’s intellectual capital, where the arts, sciences, and material progress thrived. Much of this was due to a minority whose persecution in other parts of Europe had led them to a welcoming Vienna.

By 1899, the Jewish population of Vienna had risen from 8000 in 1867 to 145,000, or about 10% of the total. They prized education and, at the beginning of the 20th century, they dominated the city’s finance (71%), law (65%), medicine (59%), and journalism (50%) sectors.

But World War I shattered this ferment of ideas and achievements. Europe’s longest-standing empire was broken up as nationalism took root among dozens of ethnicities. Food shortages and strikes reduced living standards to a bare minimum, leading to a period of socialist rule over the rump that remained of Austria, with a population of less than seven million.

The 1920s still produced much intellectual activity, led by advances in psychoanalysis, philosophy, economics, and the arts. But austerity also brought a backlash against the Jewish ‘elite’, with a rise in anti-Semitism and National Socialism.

In 1934, Vienna had a population of 1.9 million and 9% of them were Jews. Inge Ponger was born that year to parents who weren’t part of the elite but owned a motorcycle shop.

When Inge reached four, Vienna was occupied by Hitler’s Nazi Germany in the Anschluss; her parents’ business was looted and forcibly sold. They moved to Prague, capital of the then Czechoslovakia and homeland of her maternal grandfather, David Stiassny.

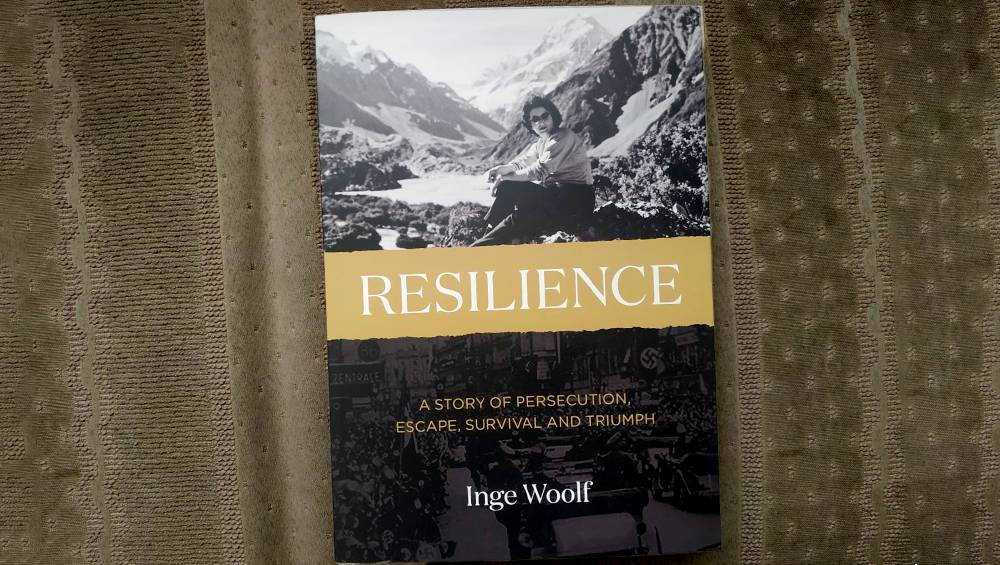

Inge Woolf.

In her memoir Resilience, published by the Wellington-based Holocaust Centre, Inge still remembers her family’s ‘conversion’ to Christianity to ease their eventual passage to freedom in England. This followed an aborted flight from Berlin that was turned back from Croydon Airport due to fog. It landed at Amsterdam and the Pongers eventually made it to London on March 29, 1939.

It is often overlooked that prejudice against Jewish migrants was high in Britain and its Empire, including New Zealand. From 1936-38, New Zealand admitted 727 Jewish refugees from 1731 applicants. Among those admitted in the 1930s was Inge’s uncle Teddy (Theodore) Stiassny.

Meanwhile, the Ponger family eked out a basic existence in London, with father Eugene (Evjen) joining the Czech émigré army because his ‘alien’ status prevented him from getting a job or being a British soldier. The mother, Grete (née Stiassny), made children’s clothes to sell at the East End’s Petticoat Lane.

Eugene’s wartime service nearly proved disastrous when it was decided he should be repatriated to Czechoslovakia, then under control of the Red Army. But he was finally released back to England in September 1946, thus avoiding a life under communism.

A son, Johnny, was born in 1949 and Eugene re-established the family’s Judaic connections. However, he was only able to get menial jobs before his death in 1955 of a medical condition aged just 50.

It was then that Grete and her children considered emigrating to New Zealand with the support of her brothers Teddy, Paul, and Karl, who all lived in Auckland. (Businessman Michael Stiassny is a son of Teddy.)

Grete went back to making children’s clothes, launching a successful business, while Inge got a job in retail, based on her experience working at a department store in Bond Street. Soon after, she moved to Wellington after landing a position at the DIC.

Simon Woolf.

This began the second and major part of Inge’s life. She married Ronald Woolf in 1959 and together they built the capital’s best-known photography business. In 1961, they acquired the Spencer Digby Studio in Lambton Quay, later renaming it Photography by Woolf. A gallery, Art Photo Décor, was opened.

It became one of the largest photographic studios in Australasia with a staff of more than 20 at its peak. I recall, as a young journalist in the late 1960s and early 1970s, how the Woolfs were held in high regard by the media. One of my jobs as a subeditor was to Iay out the wedding pages in Monday morning’s The Dominion. The Woolfs supplied many of the photos, as they did for other publications.

The Woolf archive, now at Te Papa Museum, was noted for its historic photos and portraits of the rich and famous. Official photographs included Queen Elizabeth II (still on the $20 note) and Prince Philip during the royal tour of 1987, as well as Pope John Paul II during his visit. Woolf’s portraits had distinctive lighting and a presence that were compared with those of the Canadian Yousuf Karsh.

That year was also significant for the family with the marriage of daughter Deborah to David Hart. Tragedy followed on November 20 when Ron Woolf, then aged 57, and property developer Dion Savage died when a helicopter piloted by Peter Button hit power lines. It had been diverted by a police request for help in finding an escaped prisoner. The fatal crash was national news but had one compensation.

Son Simon was supposed to be onboard but had another assignment. Earlier that day, Dame Susan Devoy had been at the studio for a New Zealand Sports Foundation portrait. She writes the foreword for Resilience. Simon still carries on the business and is also well-known as a Wellington Regional councillor and former three-term city councillor.

Simon, Inge and Deborah Woolf in Slovakia at a Holocaust memorial. Photo: Simon Woolf (2010).

Meanwhile, Inge Woolf found herself on the front page of The Dominion Post’s weekend edition in August 2004 after the desecration of Jewish graves and destruction of a prayer house at Wellington’s Makara Cemetery.

The vandalism included Ron’s gravestone and spurred Inge into a crusade to counter the same anti-Semitism she encountered in her Viennese childhood. Many who survived World War II left much unspoken when they returned to their families.

Initially, that was also the case with the Holocaust, although Resilience is one of many memoirs that have emerged in recent decades. Inge’s work in establishing the Wellington Holocaust Research and Education Centre evolved into the national Holocaust Centre, which will receive all receipts from her book.

Inge Woolf was honoured in 1992 for her work with Arthritis New Zealand (Deborah was afflicted from a young age) and finished the manuscript in 2020 but died a year later, aged 86, before the book could be produced.

It was completed by Deborah, a qualified lawyer, business consultant, director, and chair of the review into electoral law. The book also contains supplementary information on the Holocaust: a timeline of events, an historical essay by Giacomo Lichtner, and research by Anne Beaglehole on New Zealand’s record on Jewish migration (not good).

Resilience: A story of persecution, escape, survival and triumph, by Inge Woolf (Holocaust Centre of New Zealand). Released on April 11. Information: www.holocaustcentre.org.nz.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.