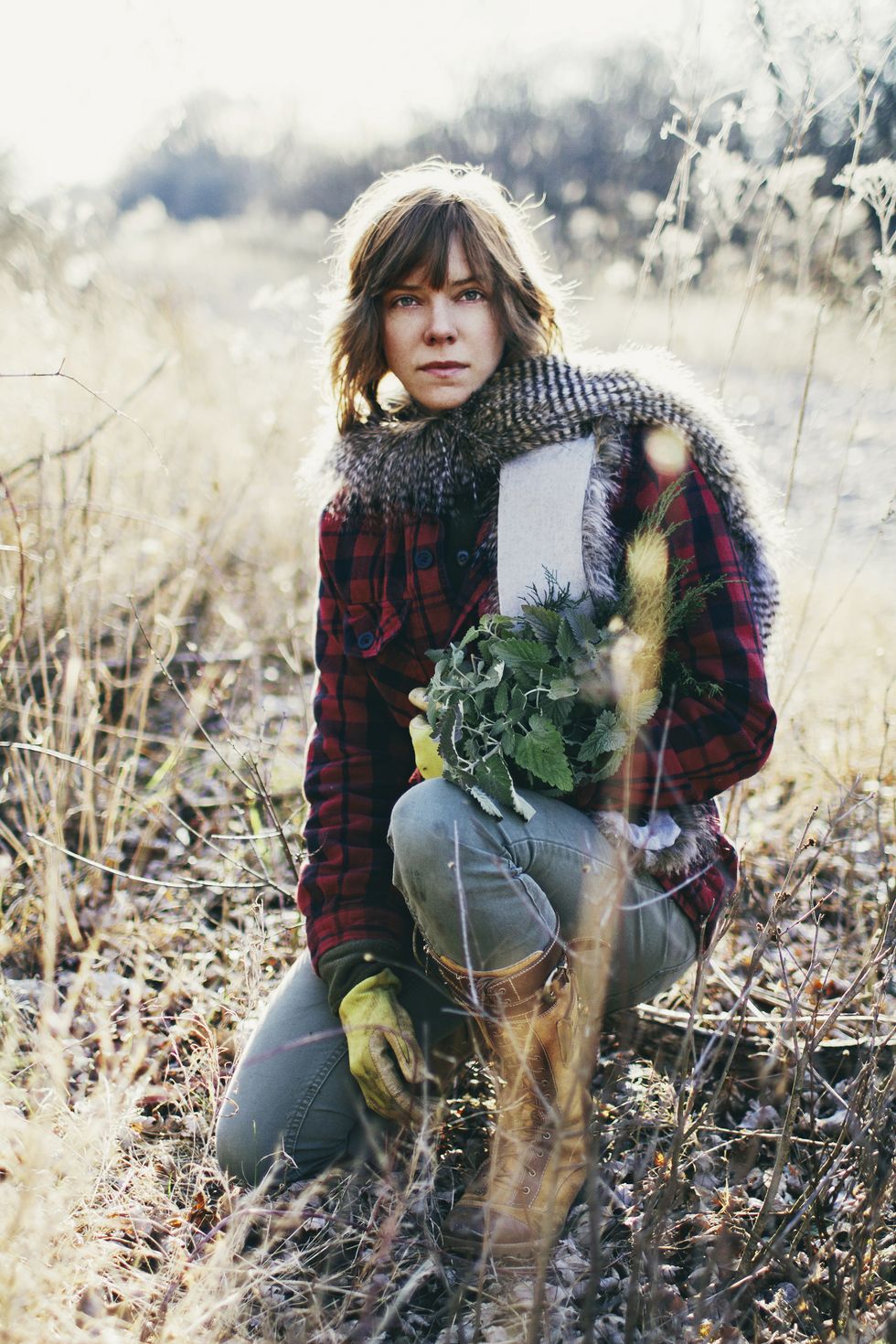

Chef Iliana Regan is young, gay, and female. She hunts for bullfrogs and accepts gifts of raccoon to inform the menus at her two restaurants in Chicago. From her childhood on the family farm in Indiana to her first kitchen job at age 15 to earning her first Michelin star for Elizabeth, where foraged ingredients get the spotlight, her life's work has been nothing if not remarkable—and remarkably different than what we've come to see in the culinary world. In this exclusive excerpt from her upcoming memoir, out in July, Regan recounts the dark, twisted day on which she knew for the first time she was a chef; she was five years old. Here is a passage from Chapter 2, titled "Chanterelles," from Burn the Place.

My grandfather’s farm, 100 acres of corn fields, oaks, birch trees, ponds, abandoned cabins, sand, wild berries, and mushrooms, was nothing short of another universe full of magic. My dad’s father, George, was handsome and sweet. We drove up the side drive, past the house, and stopped just before the large barn and gate, which led back to the woods. The path to the woods was lined with wild blueberries and dewberries and sometimes if I was there on Sundays after the Lone Ranger episodes, I’d walk the trail and pick them into a small basket. Then I retreated back to the porch with the basket on my lap and ate every single one.

George greeted us at the car. He opened the door, mostly excited to see me. He was taller than my dad. He was in his early 60s and back then I wouldn’t have known but he was better looking than most screen actors of his time. On Sundays he wore overalls and a white T-shirt. He was often on his tractor in the cornfield and today he offered to let me drive it. “They say there might be a storm today,” he told us.

My dad looked up at the sky. I looked too. Aside from some big clouds and an occasional burst of wind, it seemed like any other day that we’d come out to visit.

“Yeah, I think they might be right,” my father sort of grunted. “We’ll get moving.”

Rick removed the cooler from the back seat. He lined the empty beer bottles along the fence just before the hedgerow met the cornfield. They took the guns from the trunk. Two rifles and one pearl-handled handgun. My dad checked the safety of the handgun and presented it to me, handle iridescent and glowing. My body slumped as my arm fell beneath its weight. But I wanted to be strong—little boys are strong, so I’d have to be. I straightened back up. In 1984 it wasn’t odd that a five-year-old was holding a gun, especially in Medaryville, Indiana, but it might make someone look twice, with a slight head tilt.

My dad showed me to make a triangle with my hands outstretched before me and close one eye after the other while looking through it. The eye that saw through without causing my hands to move was my shooting eye. He removed the safety and put the gun back in my hands. He wrapped his hands around mine and knelt behind me. He told me to begin to squeeze the trigger and breathe steadily. With his index finger over mine, he pulled it back. He told me to aim at the bottle with the good eye and when the trigger comes all the way in, to breathe out. The crack of the bullet echoed as far as I could imagine. The bottle shattered. That day I proved to myself I could do anything any boy or dad could do.

“Your boy’s a good shot.”

Maybe I could be a little boy, I thought. Though soon, I’d also be reminded what of it was like to be a pretty little girl.

My dad gave me a mesh sack for collecting chanterelles. We walked along the sandy path lined with late summer berries about to drop. There was one ripe dewberry and I picked it. “How’d you know that was still good?” my dad asked. I smiled and shrugged chewing it, smashing every last seed between my teeth.

My dad kept his eyes lowered toward the ground. He scanned the landscape for what he said are mushrooms that look like orange flutes. He explained their underside were ridges rather than spores or gills. He told me I’d be good at finding the mushrooms because I was closer to the ground and my eyes were better than his.

My dad wore thick glasses, larger than his face, the broken middle—cliché, but it was true—held together by medical tape. He was clumsy and unusually nervous. He played out situations that could happen even if they had never happened before, like me getting lost right now, or falling and breaking my leg. Or a hunter that we didn’t see accidentally mistaking me for a deer and blowing me to pieces. All sorts of things that could happen, but the likelihood of their happening slim.

I’ll eventually inherit this trait.

My dad said the chanterelles would smell like the earth but also sweet like apricots and spicy like peppercorns. I said these things quietly. Back to him and to myself. Earth. Apricot. I liked apricots. Peppercorns.

The leaves were wet, and the ground was uneven. A couple times I stumbled, but I quickly became oriented. I wanted to find the chanterelles so bad. My dad reminded me to stay close. I could see him out of the corner of my eye. Rick was a little ways ahead of us and his black and red plaid jacket shone between the trees. The wind picked up and what leaves weren’t glued to one another from the previous day’s rain blew up into the shapes of cylinders then flew off between the trees.

When I stopped to tuck my lace into my shoe, as I was still inept at tying them myself, I knelt close to the ground and there it was, beautiful, orange, bright. A chanterelle. I knew it. My heart began to race as I looked further out over the multicolored landscape and saw many more in succession, like soldiers marching straight towards me, dressed in orange uniforms, determined to battle. It was amazing. I gently cut them near their base with my pocket knife. For a kid, I had good hand and eye coordination. I collected them fast and kept going, further and further. I had already forgotten everything about staying close. I could faintly hear my dad and Rick talking somewhere, or maybe it was just the wind and leaves.

Then there were two boots, right in my path. They were big, connected to legs, again big, in camouflage pants. After I stood up and tilted my head back to see who was standing less than two inches from me, I immediately turned to run back to my dad, but Uncle Georgie had already picked me up by my waist. He held me up, the back of my head to his face. I could smell his sour breath, all alcohol and old cigarettes. I silently began to cry. I didn’t see my dad or Rick anywhere. I was too scared to yell or scream or even take a breath.

“I’ll take you to your papa,” he said. I didn’t call my dad my papa.

Uncle Georgie was a Vietnam War vet. He made everyone uneasy. He was quick to snap from jolly to mad. When he came over to our house, I hid. He came over with his guns and would just shoot. The air. The barn. Toward the house. My mom would yell at my dad to make him leave. My dad, avoiding confrontation at all cost, not necessarily for our safety but because he was so empathetic when it came to his brother, would just look at my mom with pleading eyes: don’t make me do this . . .

He said he was going to take me to my dad, but he wasn’t. He walked toward one of the dilapidated cabins in the middle of nowhere. There were 100 acres. It was full of mystery and danger, like you could still see shadows of Native Americans and their horses; sometimes I thought I did, but no one else said they saw them. Someone like me could disappear there in the blink of an eye. Here he was, with his big arms wrapped around me. I may never be found again. He opened the door to the cabin, ducking beneath its threshold we entered. Through the water-bowl of tears between my eyelashes, there was Rick in his bright red and black jacket. I gasped for air. He was sitting on an old mattress near a potbelly stove, lighting a fire in it.

“Oh hey, George,” Rick said. My uncle set me on the ground. Rick was rolling a cigarette, but he put it down to reach out to me and bring me closer to him. He put his arms around me, but not in a scary way. He stood up and threw a crumpled piece of paper into the stove. He held his cigarette over it as if he were making s’mores, then took a long drag. He was the kind of guy you never saw blow the smoke out. He just kept it in his lungs somehow. Rick took my hand and led me out of the cabin. He brushed his shoulder hard into my uncle’s chest on the way.

“I think your dad found some mushrooms,” he said.

I didn’t respond.

“I know George is scary, but you don’t have to be afraid anymore. I’m here,” Rick said. Nobody would ever know Rick was a hero. I never told anyone what happened that morning. I never asked Rick why he was there, or if he knew Georgie was out there, or if he saw Georgie grab me. I was too young to think about that. Rick died a couple years later. And Uncle Georgie died not long after that.

I learned to avoid my dad’s brother. For some reason, my dad could never see him as being harmful as he really was—or maybe he just loved him so much that he couldn’t—but that man made me fear for my life. He would grab me at family functions or like this day in the woods and whisper in my ear how pretty I was: what a pretty little girl.

That was the reminder. That was the difference. I knew what it felt like to be a little girl rather than the little boy my dad said I was.

Where’d you go? Thought I lost you for a second.” My dad looked a little panicked when we came up on him. Beads of sweat formed beneath his hairline.

“Nope, right behind you,” Rick assured.

My dad proudly held his mesh sack before us. Through the netting I could see and smell the mushrooms. It was like the afternoon sun right there in his hands. Suddenly a slice of wind jetted through the trees and sent Rick’s hat flying. My dad stepped out into a clearing with a profound gaze toward the sky. The wind shifted from warm to cold then back to warm.

We began to run and as the wind grew stronger, I lurched forward beneath the weight of his large hand over mine and struggled to stay with them. I felt like we were being pushed, being chased by a thousand ghosts, or they were running with us, brushing against me, trying to push me forward, over, out of the way. I imagined all the ghosts of Native Americans on their horses slicing through us. Rick stumbled, running as fast he could, myself still dragging behind my father until he stopped and quickly buttoned the mushrooms inside my coat, then hoisted me onto his back. I wrapped my arms around his neck and he held my legs as tight as possible. It was frightening and thrilling all at once. Here is where being afraid became fun. I’d recognize this feeling for many years to come.

We ran along the same path that always felt so peaceful when it was bathed in warmth on berry-picking Sundays. Now it was dangerous as the sand began to blow up around us. Rick was like a football player charging through it as it cut around him in every which way. My father ran in his wake and I closed my eyes. When we got to the next clearing, the wind took my father to the ground. Rick slid beneath the car.

A large gray tunnel from the sky touched the ground at the end of my grandfather’s horizon. The corn bent forward as if bowing in prayer. My father reached for me behind him, but I had already been picked up in a cyclone of sand. I was horizontal, rising up through the air, much the way I imagined how the aliens would take me, or how I imagined Jesus ascending to heaven in Easter Mass.

I don’t remember all of this exactly. My memories are in large part from my father’s telling of this story. But I was picked up ten feet high, spinning in the sand. He ran after me, and about twenty feet away, I fell into a pile of hay at the base of an oak tree. There he checked my head and felt my bones, and as the wind blew, he stretched out over me, pressing all his weight to hold me to the ground. He held on to the base of the tree. After about five minutes the wind let up. The sky opened, and it began to rain. We hurried to the car and headed in the opposite direction from where the storm was traveling. We bounced over the gravel roads out to route 421 and headed back north. The car rocked along with the wind, but we felt safer, and Rick cracked a window and lit a cigarette. I rested my head against the cooler and clutched onto the bag of chanterelles inside my jean jacket. I ran my hand over the handle of the small pistol my father had taught me to use.

My mother rushed to the car as we pulled up the driveway. She opened the car door before we even came to a full stop and swooped me into her arms. She knew something had happened, but she didn’t know what. It was rare for my dad to be the calm one, but he assured her we were all fine. He avoided telling her about the sand tornado and I avoided saying anything at all. Rick leaned against the car and opened another beer.

My dad gave Rick a look that said, time to go, man.

Inside my mother changed me from my wet clothes while I repeated what I had learned about the mushrooms: “they would smell and look like apricot and be spicy like peppercorns.” She listened. It was moments like these that made her stay with my father but also hate him just a little bit more.

In the kitchen, I dumped the chanterelles onto the table. So many tiny flutes, I thought. Most of them were still good, with only a few mangled by the storm. I picked pine needles from their stems and used a brush to remove the loamy soil from their ridges.

My dad trimmed the stems. He placed a large sauté pan on the stove and moved a little footstool in front of it. On the left side of the stove he laid out butter, salt, pepper, old red wine, and thyme. The mushrooms were all neatly lined on a tray three layers deep. He asked me to stand on the stool and gave me a spoon. He told me to take half the stick of butter and add it to the pan. Once it was melted and a little bubbling we added in the chanterelles. He poured the salt into the bowl and with a few fingers’ pinched, he held it above the pan and I did the same. We let the salt drop like rain. He told me to use the handle to move the pan over the flame and gently slide the mushrooms around in the pan. He told me to put the spoon under the mushrooms, lifting and turning them so they’d get lightly browned on all sides. He cracked the pepper over it and added in the thyme while I kept moving the pan back and forth and stirring the mushrooms. He put the bottle of red wine to my nose and told me to smell it. It was sour and pinched my insides. When we added a splash to the pan the sweetness of the mushrooms wafted up and around us. I imagined I was a multitude of Russian nesting dolls all made of mushrooms. We added another pat of butter and cut the flame. I stirred the butter gently until it was creamy. He put his finger in the sauce and tasted it. I did the same. He told me to add a couple more pinches of salt and I did.

We spooned the mushrooms into three bowls and he spread our sunroom table full of his larder. Pickled pigs feet, farmers cheese, beets and horseradish, peppers and tomatoes. He opened a can of smoked oysters and sardines and placed the cans directly onto the table with forks resting alongside. My mom warmed bread she had baked that morning.

We sat down and ate a little of everything, combining the flavors and textures. The farmers cheese with the mushrooms. Swiping an oyster at the end of my fork through the creamy buttery mushrooms. The tough meat of the pigs feet with the gentle crunch of the sardine bones. The spicy beets and horseradish clearing my nose to welcome each bite of chanterelle.

This was the day I slighted fate and became a chef.