The new TVNZ1 documentary about the Mervyn Thompson Affair – when an Auckland University lecturer was tied to a tree by six feminists and beaten – treats a thorny subject with necessary ambivalence, writes Linda Burgess.

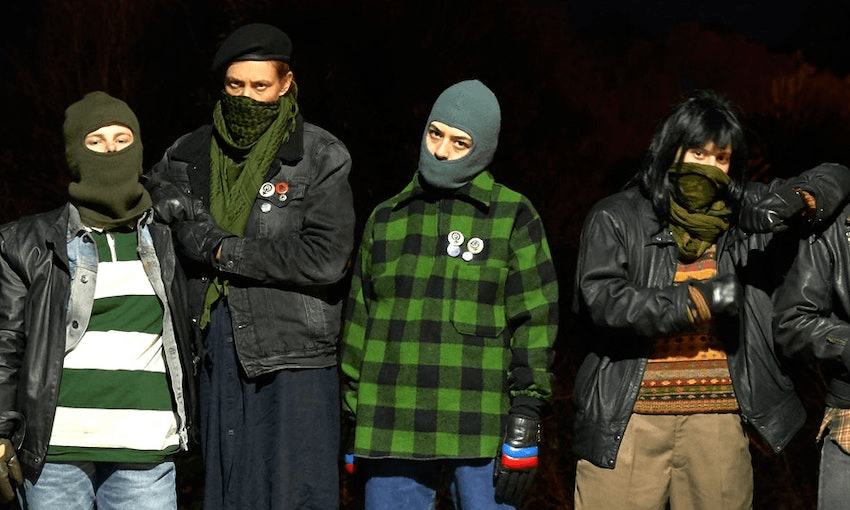

I don’t much like docudramas, or, as in this case, documentaries with re-enactments. I don’t see why you need to have some parts played by actors who look vaguely like the real person. Switching between the real and the acted is irritating and somehow implies that words aren’t enough to tell a story. Putting that personal prejudice to one side, I will say Six Angry Women did exactly what good television should do: it left you thinking. Though with forthright women like the writer Renée, who knew Thompson well, liked him, and is a longtime feminist, and the director’s mother Paula Jones, who’d studied with Thompson, available to give their considered opinions, this could have done without the re-enactments.

Mervyn Thompson was an amiable, well-liked drama lecturer at Auckland University; a socialist, an esteemed playwright. No one was more surprised than he was that one night in 1984 he was kidnapped, tied to a tree, beaten, threatened with castration, had the word ‘rapist’ written on his car and partially burnt into his flesh. As far as he – and subsequently his supporters – were concerned, he’d never raped a woman in his life.

The six feminists who attacked him, who, interestingly, have never been tried or formally identified for the vigilante attack, thought differently. The sister of one them had allegedly been raped by Thompson, and the other five had just had enough of his brand of sexual entitlement.

Six Angry Women – a nicely irony-tinged reference to the courtroom drama Twelve Angry Men – asks you to think, rather than telling you what to think. As what happened to Thompson was polarising to say the least, the docudrama is wise to take a balanced approach. You were reminded how in the 1980s most women who had been raped knew that it wasn’t worth seeking justice through the courts. As if what had happened to them wasn’t bad enough, they’d have to defend their own actions, the clothing they were wearing, their sexual history, what they were like after a couple of glasses of wine. That somehow they were complicit in their own rape. At that stage, it was estimated that only 6% of sexual attacks were reported. Cautiously optimistic, I checked current statistics. They just expressed it slightly differently: 94% of sexual attacks aren’t reported. I don’t know why I’m surprised when male world leaders openly and fearlessly treat women with disdain.

One of the many good things to have come out of the #MeToo movement is that some men have had to redefine what they previously thought of as just things heating up a bit, and him perhaps going too far, and anyway, an apology, a bunch of flowers, should do the trick. There have been centuries of male entitlement, with men using their power to do what they liked with women. The phrase “casting couch” wasn’t coined because just one ambitious actress was expected to pay for a part in a film or play with her body.

Thompson certainly didn’t see himself as a rapist perhaps in much the same way as people who casually and insistently define people in terms of their race don’t consider themselves racist. Surely rape is something that happens when a violent masked man hides in an alleyway and forces himself on a demurely dressed female stranger walking innocently past? How could it define the action of an otherwise lovely kind funny talented man who admitted having an eye for a pretty girl? Ruefully described himself as having a thing about sex? Oh God it’s a minefield. I’ve just read a Guardian interview with Judi Dench who said – when asked by her interviewer if she’d “misjudged him” – that she’d only ever known Harvey Weinstein as completely charming… perfectly polite and funny and friendly. Perhaps, she goes on to say, she was lucky… and she feels acutely for the people who weren’t so lucky – who experienced the other side of him. And there we have it.

Six Angry Women implicitly agrees with this approach, interviewing, along with a very considered policeman who’d dealt with the case at the time, a variety of women. There were those who were horrified by the accusation, those who agreed it was possible but were appalled by the attack, and those who thought he got what was coming to him. Feminists were on both sides: some interviewees relished the memory; others still feel unease. Some admitted to knowing the identities of the six women, others said even though there were rumours at the time, they really didn’t have a clue.

Because Thompson was never formally accused of rape, because the women were never identified, it means the issue at the heart of the programme is ambivalence. It’s cleverly done. It made you feel good about feminism, and how things are improving, albeit terribly slowly. It made you think about Thompson’s behaviour, and how he subsequently described what happened to him in terms very like those used by rape victims. In the end, his guilt or innocence wasn’t the issue. Mostly, it makes you wonder whether vigilantism is justified when it’s probable that legal justice is likely to be unforthcoming. The dignified fair voice of Renée thinks it isn’t. I’m with Renée.

Six Angry Women airs tonight on TVNZ1 at 8:30pm.

Read The Spinoff’s extensive coverage of the Mervyn Thompson case:

An extract from Thompson’s own bitter, furious memoir

An essay by Stephanie Johnson, Thompson’s colleague and friend, revisiting the moment

A modern take on the incident, and its wider implications, by former MP Holly Walker.

An essay by the playwright Renee, whose work allegedly inspired the attack

A look back by Talia Marshall, who grew up inside the lesbian feminist movement of the 1980s