It’s funded by a wealthy backer, and was launched as a response to the perceived failings of the mainstream media. It sounds a lot like The Platform mark two – but The Common Room has different goals, its co-founders tell Duncan Greive.

“Govt funded bs wakey wokey lighty dazzle whackeys”.“Another big government initiative, what a scam… how can anyone trust any of this?” “Another propaganda show. Nope, toilet time”.

These are just a sampling of the kind of comments that are now the default on any piece of journalism published to Facebook, ground zero for a specific variety of deep suspicion of the news media. Much of this animosity can be attributed to the Public Interest Journalism Fund, which provides targeted support for certain types of reporting and has been criticised as encouraging a too-cosy relationship between the government and the media which is meant to hold it to account.

The irony is that these comments sit underneath a recent video posted by The Common Room, a new startup media company which has neither sought or received a cent from the PIJF, but should in fact be understood in part as a critique of the mainstream media. The company is not concerned with the comments, describing them as “brilliant… we think we are on the right track”.

The Common Room says it is about “big ideas, unpacked”, and primarily produces a weekly video of around five minutes in length. The default format is to recruit someone with passion and either “professional expertise or lived experience” within a topic area to put together a script, which they read to camera. The result is then edited in the YouTube house style of the past few years – lots of cuts, bright colours and flashes of animation, and posted to social platforms and on its own website.

It is the topic selection which reveals the hand of those behind The Common Room. Though only operational for a short period of time, there is a distinct through-line visible in their videos to date. They cast a critical eye over media bias, the difference between equity and equality, what constitutes hate speech, the growth of bureaucracy, and identity politics.

A different kind of right wing media

All this is in keeping with the familiar grumbling of the right about media and left wing political aspirations – that the range of topics about which it is acceptable to have good faith discussions is becoming far too narrow. This is absolutely something that its funder and founders believe (more on them in a moment). But with The Common Room there is also an adroit sense of where the line is, and an attempt to resist pigeon-holing alongside other startups born from right wing disgruntlement over the past few years – the treaty denialism of Hobson’s Pledge, the anti-woke politics podcast the Working Group, or the anti-cancel culture furies of The Platform.

You see it in that phrase a founder used earlier, “lived experience”, a term which codes leftist and posits that those who have experienced a situation or form of discrimination are better able to discuss it. This has been accepted by many in the mainstream media in recent years, and represents a sea change from prior eras when older white male columnists and talkback hosts had a free licence to opine on racism and sexism. It seems telling that The Common Room is animated by a certain scepticism of political correctness while it also adopts the sort of language it favours.

Only, it’s not just the language. At time of writing it has released nine videos. And while five are fronted by opinionated white men, including some who have considerable experience in media, like former Seven Sharp presenter Tim Wilson, polarising history professor Paul Moon, and political commentator (and Spinoff columnist) Liam Hehir, there is also more than enough diversity of identity to deflect a dismissal on those grounds.

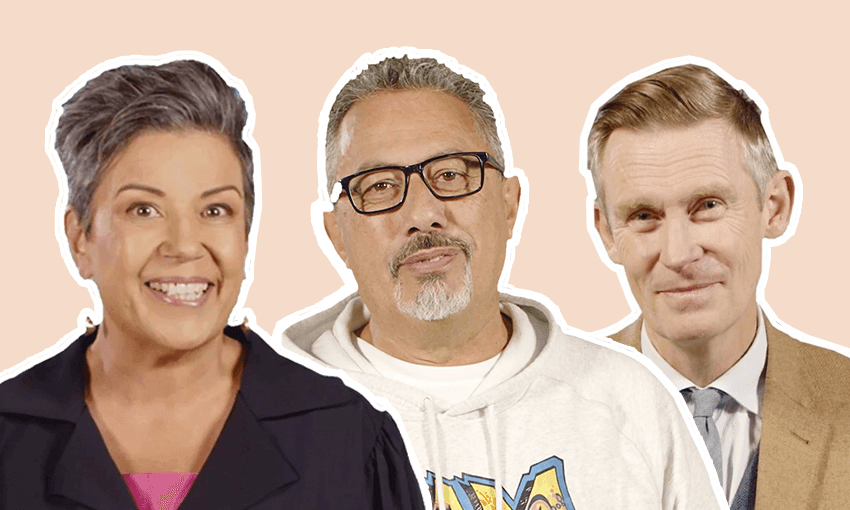

There’s Melissa Darby (Ngāti Ranginui), a senior lecturer at Waikato University who detects a shift in emphasis in government policy from equality to equity. There’s Mike King (Ngāpuhi) doing Mike King things, and Paula Bennett (Tainui) talking about how she became a right wing person. Most compelling is Ronji Tanielu, a community worker from Māngere, who offers a critique of centralisation, and an argument in favour of more resourcing of community providers to be funded to come up with their own solutions to challenges which face them.

Which is to say that while it does present a fairly coherent contemporary right wing ideology (free speech is important, small government is good, identity politics is too reductive etc), it does so using a cast of presenters who makes those seem like plausible concerns for all New Zealanders, not just the ageing Pākehā typically associated with them.

Who opened The Common Room?

The Common Room is the brainchild of Mike Ballantyne, a former advertising creative who went on to found the phenomenally successful travel platform Online Republic, which was sold to Webjet for a reported $85m in 2016. He met co-founder Lou Bridges at an event last year, and the pair found themselves swiftly in discussions about the media, the kind of debates which weren’t happening, and what could be done about it.

Bridges is a “former rag trader”, who worked in different aspects of the garment industry for decades. She describes herself as having been completely uninterested in politics growing up, before marrying someone for whom it was perfectly normal to discuss political and social issues around the dinner table. She and Ballantyne both identify as centre-right, and Bridges remains involved with the National Party through its most conflicted electorate, Epsom – a stronghold Act first won in 2005, but has since endorsed their rival in (although Seymour might well win it even if it were contested nowadays).

At The Common Room, Ballantyne is the one who funds it and works on the product, while Bridges says her “superpower is really getting stuff done”; she wrangles the talent. From a standing start in February, they hustled to debut their first video on August 9.

That debut video features the academic historian and prolific author Paul Moon arguing that our current laws are adequate to deal with hate speech, and do not need strengthening. He says “the proposed hate speech laws will impinge on your rights to express your ideas with friends, at school, at university and in the workplace.” The tone is open, accessible, very much not aimed at the hyper-media literate – more at those who might get served the video by search or algorithm.

Moon himself is not a stranger to controversies over speech, having authored a book which attracted controversy due to its focus on Māori and cannibalism. There was an understandable furore at the spectre of a Pākehā academic wading into such a sensitive and charged area. He defended it in an op-ed in the NZ Herald which opened by comparing the response to Nazi book burning.

Moon’s video is perhaps the most explicitly political. Liam Hehir’s is more typical – he addresses media bias in a very even-handed way, suggesting a structural explanation for a slight leftward lean which does not seem particularly controversial. I asked Hehir what attracted him to The Common Room.

“There were a couple of things I liked about their pitch,” he wrote in an email. “First, they wanted to do things properly, with good production values using a format that is proven overseas but new to New Zealand. Secondly, they were after contributors to explain their views for a general audience. Finally, they agreed that this kind of venture can only succeed if it takes a civil and agreeable tone.”

Based on their first videos, they have largely stayed within those lines. The tone is even, the arguments based on fairly standard centre-right philosophy. That’s deliberate, says Ballantyne. “There’s a lot of polarisation. And I’m not pointing the finger at anyone, it’s just kind of the way it is. We were genuinely interested in sparking fair and honest conversation with New Zealanders, whether that’s around the dinner table, or the barbecue, or even in the public square.”

There are certain issues which are flashpoints, that are of consuming interest to different communities on social media, but Bridges and Ballantyne are wary of getting too close to the culture wars. Trans rights, abortion and vaccine mandates are all off limits. “While we’re establishing, we just want to go after a lot of issues around the economy,” says Bridges. She sounds very much like Christopher Luxon’s National Party, which is keen to not talk about those hot button issues that might excite a segment of the base but alienate more moderate audiences.

What is the long game here?

Ballantyne has something in common with Wayne Wright Jr, the rich lister who is ploughing millions into Sean Plunket’s online radio station The Platform. Both are interested in media but are not from media, both felt that important discussions were not being had, both are independently wealthy enough to be able to run media businesses in a way that isn’t just not-for-profit, but seems to have no plausible path to material income, at least initially.

In some respects Ballantyne could scan as a scarier prospect, in that he and Bridges are functionally the editors of The Common Room, while Wright appears to truly be leaving all that to Plunket. Yet temperamentally both Bridges and Ballantyne do appear to be as moderate as they say. Ballantyne mentions a forthcoming video featuring a prominent economist who sounds a lot like like Shamubeel Eaqub (they won’t reveal their identity), that poses the question: “why would you cut tax when the health system is in such disarray, or education needs serious investment?”

Along with an ideological sense of where the content should sit, Ballantyne is also bringing some of the mentality with which he ran Online Republic, and is happy to fund The Common Room until he sees proof that it is worthy of outside investment. “I want to prove that there’s something there before I go and talk to other people about it… my wife and I are committed to funding in the first instance, to get it to a point where we can say people are engaging with this content.”

That is not front of mind for them, though. This is explicitly about debate, and filling what they feel is a hole in our public discourse. This is what has Hehir engaged with the project. “Even if you can’t change minds there’s social value in different perspectives feeling heard,” he says, and it’s true that when communities don’t believe their views are expressed in mainstream contexts, frustrations are likely to grow.

Historically there was little that could be done with that feeling, but both The Platform and The Common Room express the dawning of a new media age, in which the costs of creation and distribution have sunk so low that high net worth individuals can easily create their own channels and disseminate views they see as being missing from the larger conversation.

The difference with The Common Room is that its founders do appear genuinely motivated to build something which, contrary to international trends, is a determinedly normie centre-right platform. Of course, The Platform said that too, yet within months has become infested with anti-vaxxers and conspiracism. This has led to huge five figure views on Platform videos featuring its most troublesome guests, while the more restrained work from The Common Room is more likely to attract viewers in the low hundreds. It’s early days, but media operators tend to eventually realise that the algorithm loves extremes.

The broader media environment is flush with suspicion and opportunity for further trust decay – particularly should the government complete its planned merger of RNZ and TVNZ, with the extra funding that goes with it. For now, both Ballantyne and Bridges say they are determined to avoid pouring petrol on the current fires, and view The Common Room as a legacy project, the kind that will be spoken about at their funerals.

That’s where it starts, but as Bridges says, “who knows what we’ll be talking about in two years time?”

Follow Duncan Greive’s NZ media podcast The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.