The National Business Review reported a comment by New Zealand’s then National Party government minister of finance Bill English on August 15, 2014, that he had occasionally pointed out in speeches to business audiences that New Zealand has had post World War Two recessions roughly every 10 years: in 1957-58; 1967-68; the mid-1970s; the mid-1980s; 1997-98 and 2007-8. He would observe laconically: “You’d think we would see them coming.”

But of course bourgeois economists, commentators and journalists don’t generally see them coming. One problem, however, is that sometimes the Marxist critics of capitalism see them coming a little too often.

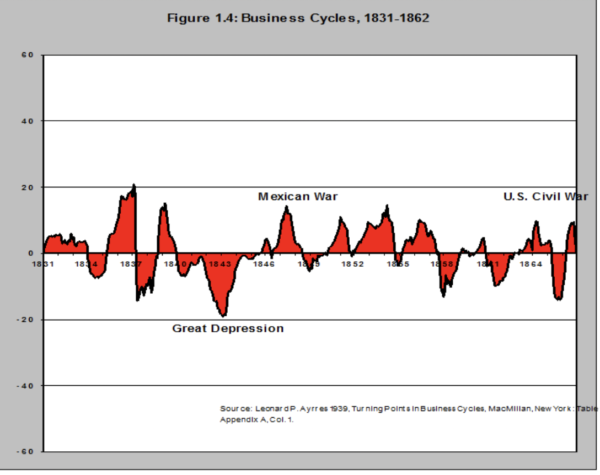

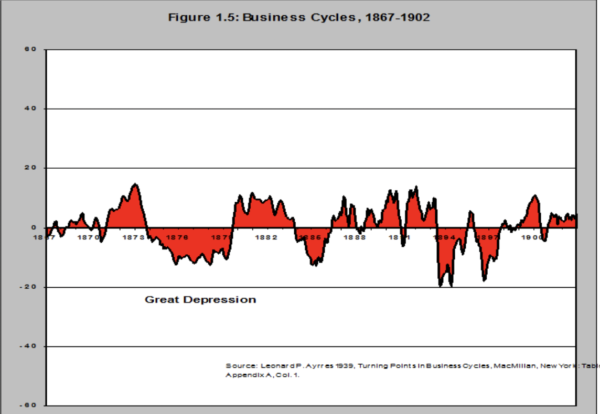

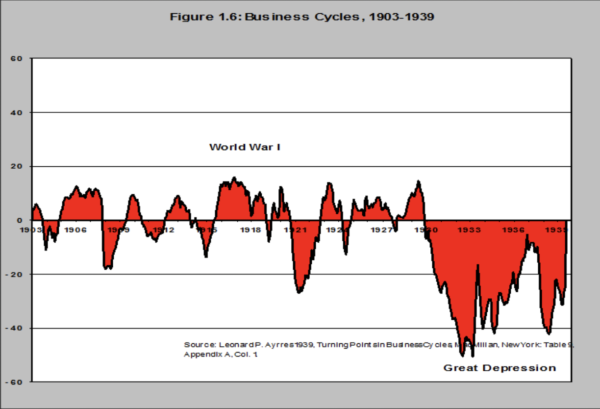

But it is a simple fact of life that capitalism has had economic crises on a periodic basis at least since 1825. Every 10 years or so, capitalism goes through a cycle of boom and bust. The following charts for the US economy illustrate this reality. They have been taken from an important paper by US Marxist economist Anwar Shaikh entitled: Profitability, Long Waves and the Recurrence of General Crises

Capitalism also goes through historical periods where the industrial cycles of boom and bust are more pronounced one way or another. That is, capitalism goes through periods of several decades such as the post-World War II “long boom” involving multiple cycles where the upturns are relatively stronger than the downturns.

Similarly there are other periods such as the decades following the crisis of 1873 where the upward phases of the cycle are relatively weak and the downward phases more pronounced.

Understanding these cyclical fluctuations is also closely connected to another element of Marxist theory that is important to explaining what is happening – historical materialism – which is simply a way of viewing and understanding history.

Societies, ever since we humans began generating a consistent surplus, have been divided into classes where each class is defined by its relationship to the means and mode of production. The legal, political, social and cultural elements of society arise from this economic foundation.

The relations and modes of production, which determine how the economic system is produced and reproduced, have gone through various stages as technology and the forces of production have advanced. The main stages have been slavery, feudalism, capitalism and the beginning efforts to construct socialism.

Economic systems do not pass away until they have exhausted their progressive functions in terms of increasing society’s productive capacity, which in turn enables population growth and cultural development. When the growth of the productive forces reaches a certain limit within the framework of the existing society, the question is posed: Can the fetters of the existing social relations be thrown off and a new society established?

Marx’s answers

Marx devoted his life to answering this question in relationship to capitalism. This was the question from his point of view. Decades of research, decades of writing, decades of reflection – in between throwing himself into labour struggles and the odd revolution when they were happening. But he always returned to this basic task.

The key questions for Marx were understanding why capitalism operates the way it does and whether capitalism is a historically limited system – whether it will reach a limit and need to be superseded. Marx’s answers are to be found in his writings, especially his great work known as Capital.

Our inability, so far, to supersede capitalism on a world scale means that periodic crises return again and again, each one causing great hardship while also giving a powerful impetus to the centralisation of capital and the growth of monopoly domination.

The system’s dependence on relentless expansion over time and its inherent drive to maximise profit rather than meet human needs means that we now face the incompatibility of this system with our coexistence with Mother Earth.

That has become an element of crisis theory in the broader sense – demonstrating the increasing incompatibility between a livable environment and the way the system is organised through private property and ownership.

The crises, therefore, tend to get bigger, more prolonged and more socially destabilising. I think we have entered with the 2007-08 world recession, the weak recovery following and now the post Covid boom and bust in rapid succession, a new opening of a prolonged period of crises like that.

But there is no final crisis in this system – other than a descent into nuclear war, or barbarism arising from the sort of ecological winter or runaway ecological collapse that capitalism appears to be preparing for us. Short of such a disastrous outcome, the system will continue to carry on with its booms and busts until it is overthrown and replaced.

That can only be carried out by a conscious social and political force, by a class that is not bound to the system by material interest. That is why the working class is the only class that can overthrow this system. It is the only class not bound by property and profit to its perpetuation. It is the only class with the numbers and social power, if organised, if conscious enough, to effect this outcome and bring about real majority rule.

Marx’s challenge

The problem faced by Marx was that the challenge he took on in his writing of Capital was so daunting that all we got during his lifetime was the first part of a planned six-part work.

Marx published a volume 1 which was part of his planned first volume in several editions. Engels, using Marx’s notebooks, produced what we know of as volumes 2 and 3 after Marx’s death. Then there was the Theories of Surplus Value – a part of a rough draft of a history of economic thought. All of that was originally going to be the first volume of the planned six-part project.

There were to be additional volumes on wage labour, the state, and competition. The entire work was to culminate in the volume on the world market. It was there logically that crises were to be dealt with in a systematic way. Marx does not deal with crises except in scattered references, mostly in volume 3 of Capital and in his correspondence.

Marx’s method was to begin at the most abstract level before moving progressively to the more concrete. In Capital he begins with the abstract categories of the commodity and value and moves through to the formation of prices and the role of money and the market.

He goes on to explain the origin of profit in surplus value and ties this all in with the origin of capitalism in what he called “primitive accumulation”. Systematic treatment of things like exchange rates, world trade and so on were to come later.

There was an added problem with what we know as volume 2, published after Marx’s death. Volume 2 is actually more a volume about how capitalism works rather than how it doesn’t. Marx explains how capitalism must be a system of expanded reproduction and he presents formulas to prove that is how it must exist and in a sense how it can exist.

There was a certain consternation and debate inside the socialist movement when volume 2 was published. The revolutionary ideas of Marx and Engels were already under attack within German Social Democracy, the German workers’ party at the time, which was led by followers of Marx and Engels. Volume 2 was used by critics of these revolutionary ideas to “prove” that capitalism worked and could last indefinitely – in support of the views of the reformist wing of German Social Democracy led by Eduard Bernstein.

Because the cause of crises wasn’t fully spelt out in Marx and Engels’ work, revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg started to look for explanations for why crises happen that didn’t quite fit in with the logic of what Marx and Engels had written. She looked at the exhaustion of the world market. Others, like Henryk Grossman, looked at things like the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, which was viewed as a long-term historical tendency by Marx.

This logic of Marx’s method can today be deduced not only from their major economic works but also from their journalism and correspondence in which they wrote about and analysed actual crises until Marx’s death in 1883 and Engels’ in 1895.

Capitalism has also changed significantly since Marx and Engels wrote. These changes need to be incorporated into our understanding of crises today. The system has evolved from industrial capitalism based on free competition to monopoly capitalism.

We have been through the Great Depression of the 1930s. We have had the experience of the “Keynesian revolution”. We have had the Monetarist counter-revolution inspited by US economist Milton Freidman and the debates in economic theory around that.

We have also had an end of the international gold standard, a very important event. We had the stagflation of the 1970s, and the neoliberal turn in the 1980s.

Most recently, we have had the global “Great Recession” of 2007-2009, followed by an unprecedentedly weak recovery, anaemic at best for most of the world. Monetarism appeared to be abandoned briefly in favour of Keynesianism again in order to confront the Covid crisis only to be reimposed to crush the inflation unleashed in its wake.

Today we are facing a renewed global recession that threatens a return of a great depression. This is because the weak recovery after 2008 still required an enormous explosion of debt. This was followed by the inflationary money printing to cope with the Covid-19 crisis that will require interest rates we haven’t seen in decades to bring under control. That, in turn, will provoke a cascade of debt and broader financial crises across the globe.

Wee farmer billy aye. Been to Dipton? Dipton’s a lovely, tiny little town in West Southland with fantastic views of mountains and over some of the most beautiful and productive farmlands in the southern hemisphere. ( Farms are where people grow things to eat and stuff to wear for money. FYI. )

It’s also traitor country. Aye, Wee Billy?

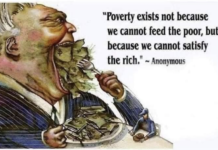

“Communist memes aren’t funny”

Full Marxs for that one

I agree it must be the working class.

What I’m not seeing yet, is how a Marxist analysis helps us in the current, critical circumstances of this sorry world and where the poorest are at the frontlines of all the problems, and already struggling to survive. And on seem to be tasked on top of all of this, by the urgent need to solve global crises.

It may have been Winston Churchill who said Democracy is a very bad form of government but the others are so much worse. That’s how I feel about capitalism and the other alternatives. If we don’t have capitalism as our economic system where hard work, imagination, innovation and energetic commitment, can be rewarded by increased wealth and social standing, what do you replace it with that doesn’t drag us all down to the common denominator at the bottom. Capitalism sucks but I haven’t observed anything better out there.

Totally agree. Capitalism is best, but uncontrolled capitalism is the problem.

Capitalism can be self controlled by ethics, moral values, religion, and/or rules, regulations, laws by an ethical & visionary govt that cares about the long term development of the country.

However, govts and religion are blinded by money, power and poor knowledge. Example, Grant being minister of Finance, the guy who has not studied a single paper in Finance.

Uncontrolled capitalism is here to stay, and will continue to destroy families, society and the country.

benny give a practical real world instance where capitalism ‘self regulates’ a historical one do if you can’t find a contemporary one.