TL;DR: Once a year, every year, from now on, in our not-so-slow-cooking climate crisis, there will be a moment when the most important number in Aotearoa’s own personal, national and financial economies could implode. It is the day when the annual home insurance renewal letter arrives to advise there will be no renewal.

Reserve Bank (Te Pūtea Matua) analysis released this week showed 25% of Auckland’s homes could be affected by rising sea levels and/or a 1-in-100 year type of storm, with some vulnerable to a complete wipeout of their values. It also showed a ticking time bomb underneath those home values that could go off once a year, rather than whenever the home has to be remortgaged or sold. But luckily, for the economy, the bank regulator found our banks are strong enough to cope with any devaluation shock/s, although those owner-occupiers and landlords stuck with unsaleable properties face decades of repaying a loan they’ll never be able to clear with a sale, unless they can convince a Government or Council to buy them out at pre-flood land values.

Those home owners with loans, but without insurance, face a type of never-ending zombie climate apocalypse — locked in to repay the mortgage and unable to move without being wiped out financially, and facing the risk of being wiped out physically in a flood or storm surge. Unless they can flick on their timebomb to someone else without the information or belief that it can happen to them, or perhaps the confidence there will always be a taxpayer or ratepayer to buy them out because they are special. They can then try to argue they didn’t know and couldn’t imagine their home was at risk, and that the letter in the mail from the insurer was Act of God.

An economy with a climate landmine underneath

We’ve suspected it for years, but no one had ever compiled the overlays of the flood plain maps, the bank mortgage portfolio maps, along with estimates of the possible climate events and the resulting potential losses for homeowners, banks and insurers.

Now the Reserve Bank has done it for the first time, if only for Auckland. It has published its first 13-page 2022 Flood Risk Assessment for Residential Mortgages paper in its latest bulletin, which has started the process of lining up the climate forecasts, the bank loan book maps and the projected flood and sea level changes on those maps. Think of the exercise as a bit like combining the valuation maps in Homes.co.nz with the flood plain maps at NIWA and the five spreadsheets with addresses and mortgage balances from the biggest banks.

It is the map that shows who is sitting on climate landmines, and how much it might hurt when they are triggered by a flood or a re-valuation, or most likely, a letter in the mail.

The results are sobering, if only because they signal this is only the beginning of the process because the analysis does not include all the data on risks in all of our housing markets, which (I would argue) make up the engine rooms of our economy (with bits tacked on).

The key things to know from the report are:

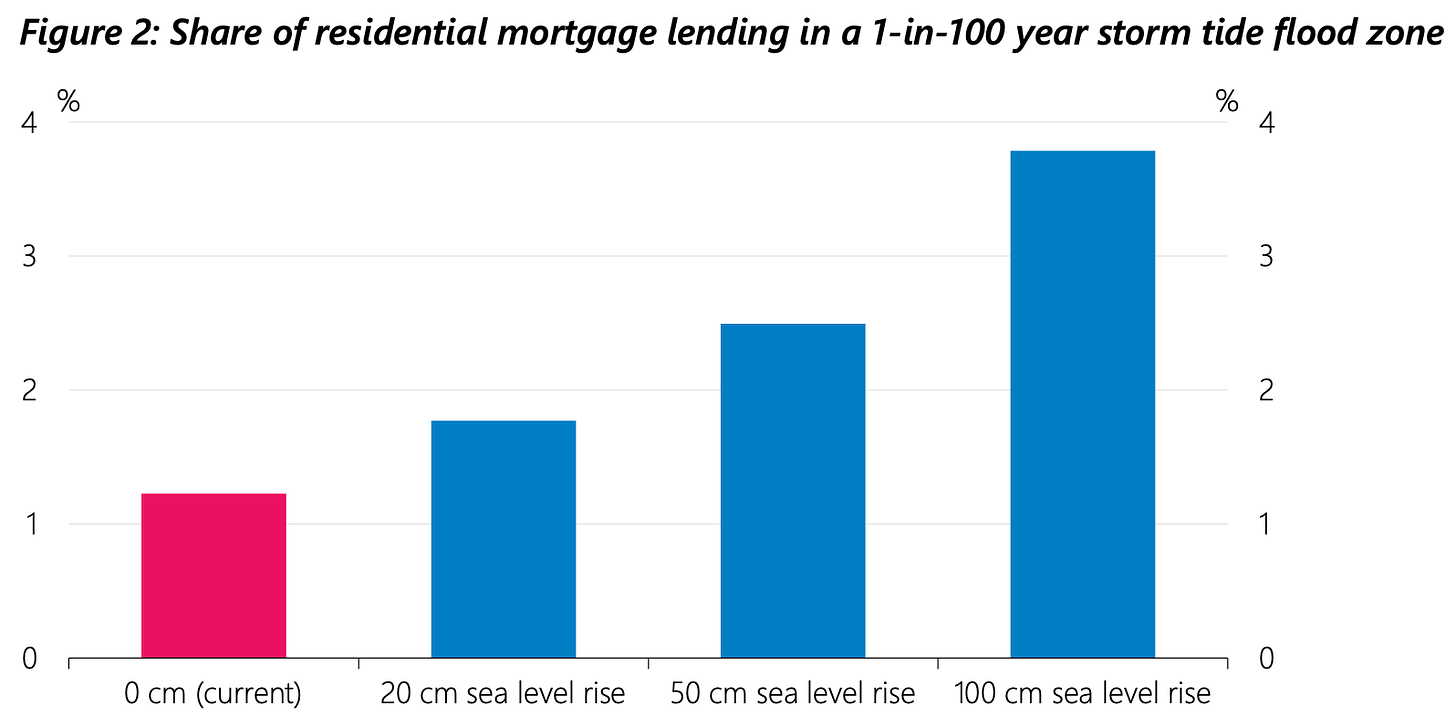

nearly 25% of mortgages in Auckland are deemed at risk in a 1-in-100 year flood event;

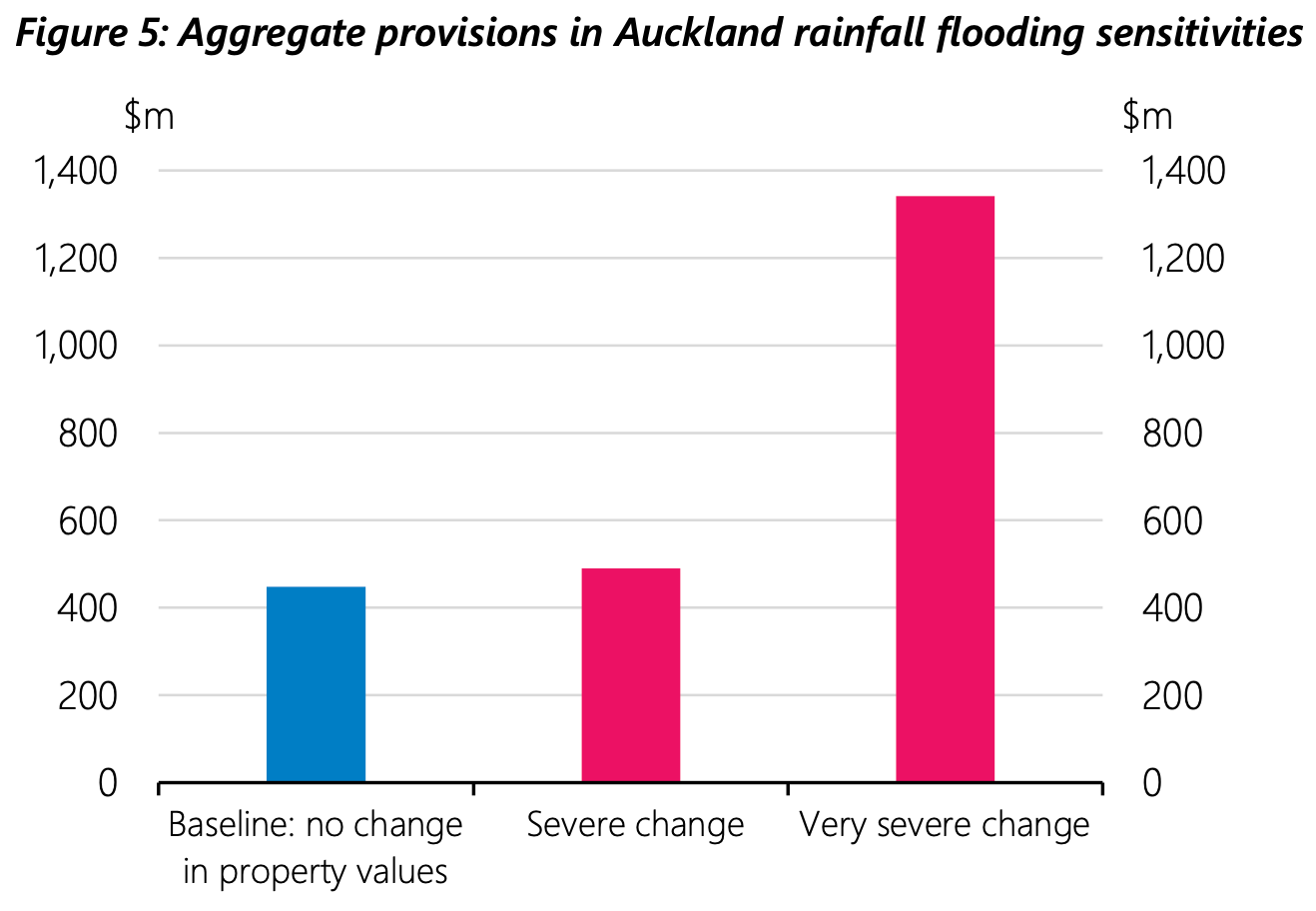

possible provisions for bank losses could rise as high as $1.3 billion in the most severe events, and that estimate is for only half of Aotearoa’s mortgages because it covers only mortgages in Auckland (which has half of the motu’s home loans); and,

the trigger moment for a loss of value in a home (or more accurately the land value under the home) is more likely to be the annual insurance rollover event, rather than a sale and/or re-mortgage event.

For me, this was the most chilling bit of the paper (bolding mine):

Insurers generally issue insurance cover on a 12-month term, meaning that annually they can re- evaluate a policy based on any new information or understanding gained regarding the risks associated with a property or area, or a change in the cost of re-insurance.

A change in the affordability or availability of insurance could trigger a fall in property values, as reduced insurance cover would shift greater risk onto homeowners and lenders. This could occur quickly given the annual insurance cycle.

Other factors that could see decreases in flood-affected property values include greater homeowner awareness and risk aversion when buying a property in a flood zone, lower rental income, a sudden increase in flood zone properties for sale in anticipation of future events, or a reduction in the quality and provision of key infrastructure in flood-affected areas. Reserve Bank Bulletin paper.

Beware the letter, rather than the flood

What this means is that the first a homeowner will know their family’s savings have been wiped out and they can never sell for a decent price is when they open the letter from the insurer telling them they have either made the premium unaffordable, or their home is uninsurable. The trigger is not the flood. It is the moment when an analyst or risk manager at your insurance company recalculates the damage costs for your property after a fresh set of NIWA forecasts and maps, or a fresh reinsurance deal. It will be like a neutron bomb where the only sign it has gone off is the letter from the insurer regretting to inform the customer that their home is either uninsurable, or the premiums are so expensive that it may as well be uninsurable.

Anyone wondering what that feels like or looks like should talk to the owner of a Wellington apartment deemed earthquake prone with the swipe of a mouse in the years after the Christchurch and Kaikoura earthquakes.

The caveats and other ways the numbers could be bigger

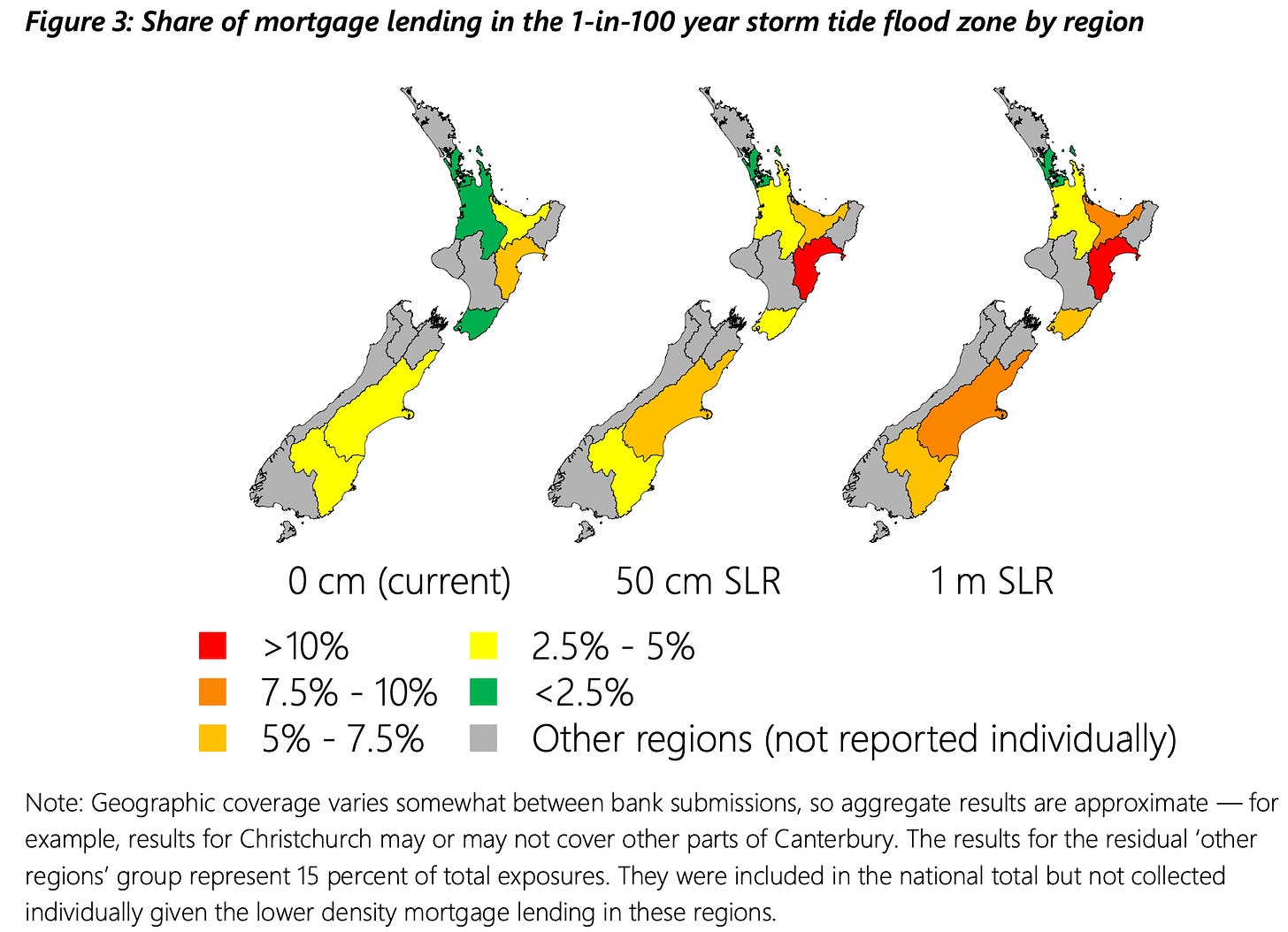

But this is just the beginning because the Reserve Bank made clear in its paper that it only analysed the detail of the mortgage books and flood maps in Auckland, which is actually less at risk in percentage terms than Christchurch and Wellington, and did not include the Hawkes Bay, which had the biggest risk of flood damage to homes.

The analysis was also done before Cyclones Hale and Gabrielle and did not include any coincidental and quite likely changes in economic conditions from climate events, including unemployment. The prices used were also in March 2022, before a 12% fall in prices nationally wiped out some of the buffer the banks could rely on before having to provision for losses. The Reserve Bank will re-do the numbers later this year in its 2023 Climate Stress Test of bank books, which may be made public in or around its November 2023 or May 2024 Financial Stability Reports.

Here’s the other caveats from the Reserve Bank, none of which would make the numbers smaller:

Since then, house prices have fallen and mortgage rates have risen, making customers more vulnerable to the shocks considered in this exercise if we were to re-run it today.

We will explore this in our 2023 Climate Stress Test and are using these sensitivities to guide our scenario design.

Additionally, we are aware that flood risk is only one channel of financial impact that may be borne from climate change at the coast. Coastal erosion, for example, is not in scope of this exercise but is a climate-related risk we will consider incorporating in future.

Nor were the effects of loss and damage of key infrastructural assets such as road and rail links, electricity and communications transmission hardware, and storm and wastewater drainage systems, which are often located within zones vulnerable to acute coastal inundation impacts.

So what could these second round effects look like? The Reserve Bank gave a helpful comparison:

In this respect, the infrastructural damage caused by Cyclone Gabrielle may offer a window on the wider community and economic impacts of acute events which financial institutions may learn important lessons from.

So what did the analysis include?

The Reserve Bank asked the banks to use the current (ie not updated with Hale or Gabrielle data) 1-in-100 year storm tide level at each sea level when defining a flood zone, which doesn’t itself adjust the scale of the 1-in-100 year event for a changing climate. Banks also used different versions of maps, suggesting better ones may well generate bigger numbers.

This means we are not capturing a change in the size or nature of the storm surge due to change in climate. However, the hypothetical changes in insurability and prices of properties in the flood zone are severe enough to be consistent with increased frequency of the storm tide event.

Banks used flood maps matched to location data to identify ‘at-risk’ properties in their residential mortgage portfolios. We asked that a property be classified as ‘at-risk’ if any part of it sits within the flood zone. However, in an attempt to support the ongoing capacity building of the banks, we did not specify use of a particular flood map for coastal zones or the type of spatial data set; this leads to some variation in the data and approach between participants.

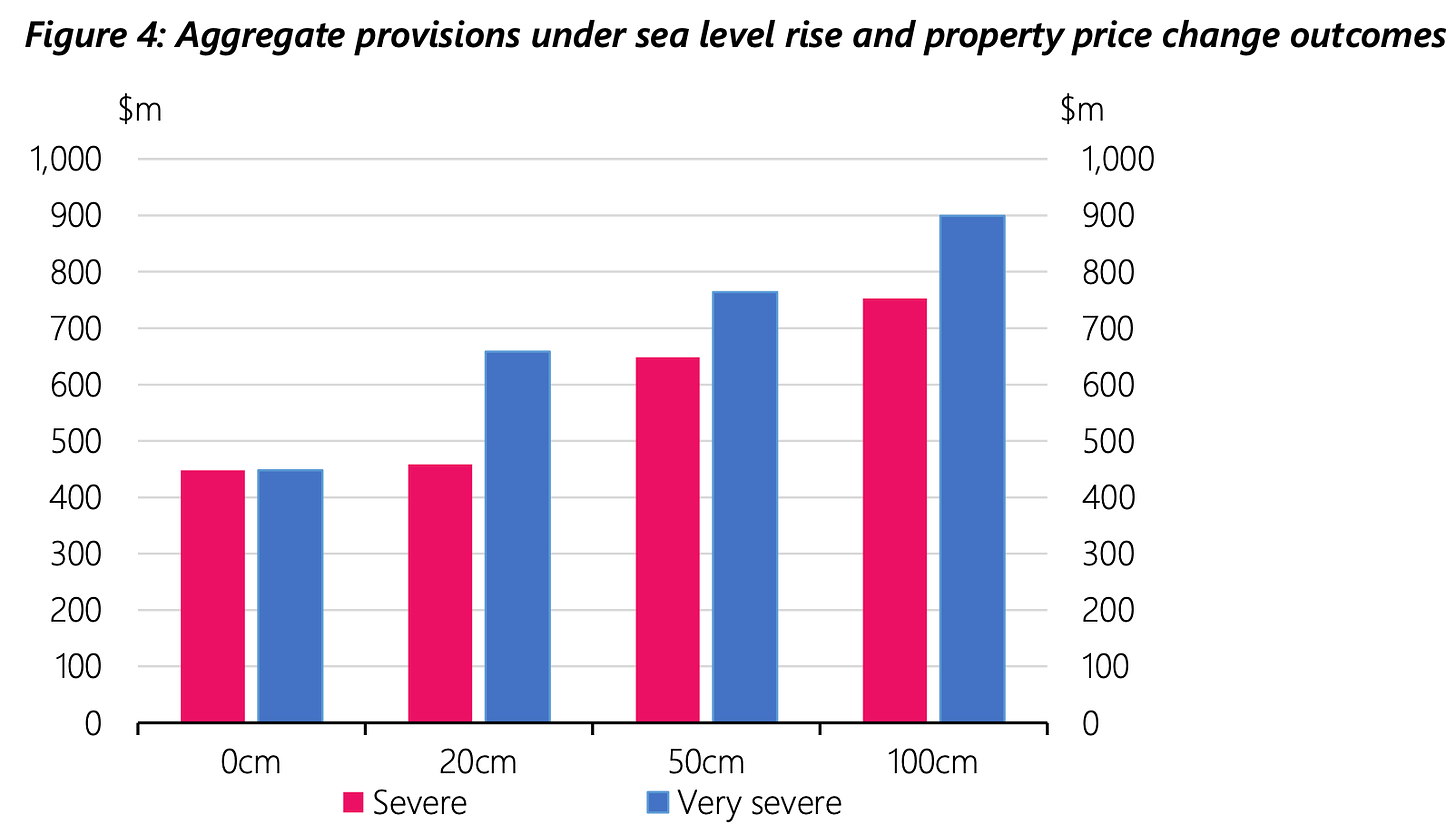

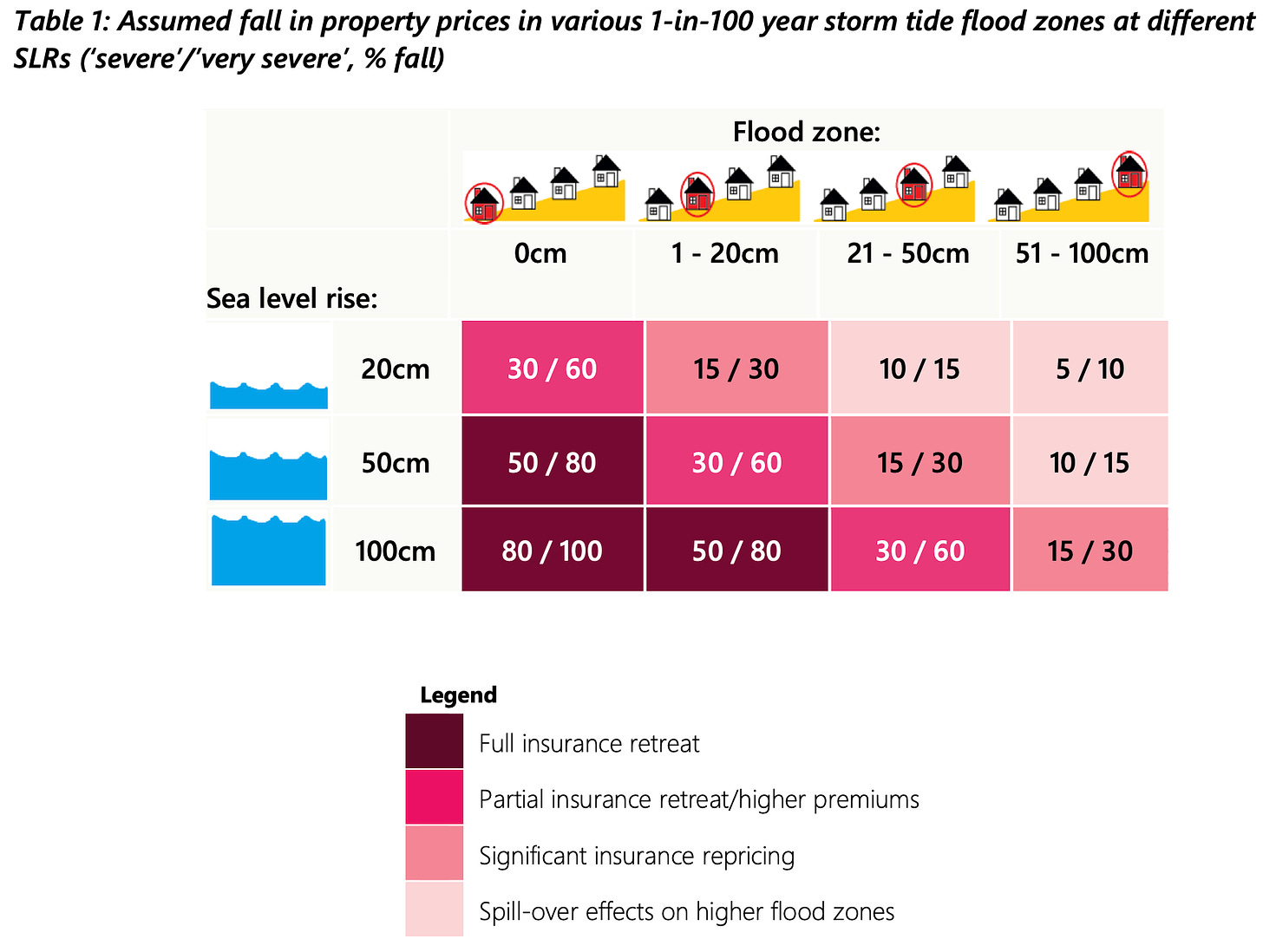

The analysis found that 2.5% of the total dollar value of residential mortgage lending was exposed to the coastal flood zone with 50 centimetres of sea level rise. It rose to 3.8 percent in a more severe outcome with 1 metre of sea level rise. The banks’ data showed that with 50 centimetres of sea level rise, Christchurch contributed 22% of the national exposures, followed by Wellington with 14%. The data for Hawkes Bay found 15% of lending was exposed to a 50 centimetre sea level rise and 20% to a 1 metre rise.

The analysis found, understandably, that those homes closest to the sea were more likely to see their total value wiped out if seal levels rise by one metre.

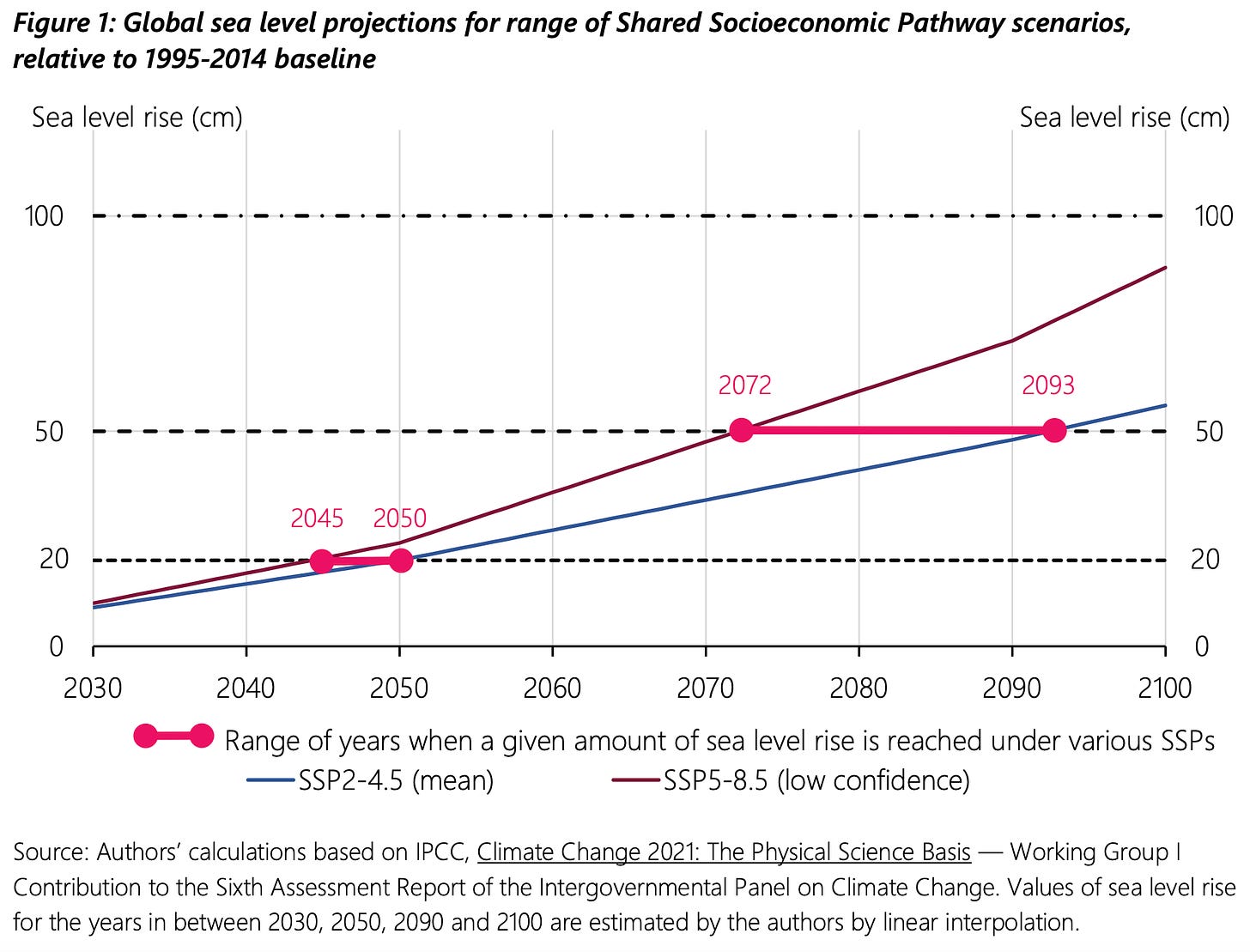

The Reserve Bank used the estimates from the IPCC of potential sea level rises with various levels of warming.

The Reserve Bank asked the banks to calculate loan loss provisions for mortgages affected in the flood zone, taking into account customers’ ability to service the loan and changes to the underlying value of the property.

Loan servicing is the key and explains why the potential bank losses are much, much lower than the potential loss in property values. The banks will be able to enforce its contract specifying the owner must pay the mortgage, regardless of the value of the property, as long as they have a job. Owners can be wiped out financially in wealth terms, but as long as they have regular income, the bank will be fine.

The impact on capital is small due to the low number of properties exposed to coastal flooding risk. The aggregate CET1 (common equity tier one) ratio declined by only 16 basis points (0.16%) for the most severe assumptions.

The results do not assume any increase in the unemployment rate that would occur during an economic downturn. If there was a period of elevated unemployment coinciding with these property price falls, the risks would compound and we would expect the effects of the assumed price declines for at-risk properties on banks’ provisions and capital to be significantly greater.

This exercise shows that if sea level rise were to be the only impact of climate change facing them, our largest five banks, given current balance sheets, would be resilient to rising sea levels and hypothetical severe falls in affected property prices. Given that even at our most extreme sea level less than 4 percent of mortgage lending is exposed to the 1-in-100 year storm tide, we would expect this level of resilience.

Even in the most severe scenarios, bank capital levels fell just 41 basis points.

Even rising sea levels plus big floods won’t damage banks too much

The Reserve Bank also asked the banks late last year to assess their sensitivity to a major rainfall event in Auckland. Some of the economists there should perhaps become weather forecasters.

As with the coastal sensitivity results, the Auckland rainfall sensitivity shows that flood risk driven changes in property values would affect the capital profile of the largest banks in Aotearoa New Zealand, but not to a degree that threatens their solvency or business model. However, these provisioning expenses would reduce bank profits, and potentially dividends. Moreover, if flood risk went unmitigated this would, however, put entities in a position where they are more vulnerable to other shocks such as an economic downturn.

But wait, there’s more

The Reserve Bank’s main conclusion was that simply modelling the affects of the storms and rising sea levels on their own would not be enough.

We are also aware that as flood risk increases, the financial system is likely to face simultaneously a broader range of climate-related risks: domestic transition risks from factors such as more stringent emissions pricing; transition costs transmitted internationally, for example shifts in market preferences or diminished market access through mechanisms such as border taxes; and the longer term effects of the increasingly severe chronic and acute physical impacts of climate change on the reserves of adaptive capacity in the wider economy and the financial system. Our forthcoming Climate Stress Test will be designed to improve our understanding of the combination of climate-related risks to banks’ balance sheets.

So this won’t be the last of it, as note 13 in small print at the bottom of the last page spelled out with the most clarity and foresight:

This will be a stress test against a multi-decade scenario involving physical and transition risks across various parts of banks’ businesses; for example, flood risk will affect commercial property and agricultural borrowers as well as residential property. The stress test scenario will include acute flood events, unlike the sensitivities presented here.

Get ready for the letter that triggers the landmine

These climate stress tests will be annual or semi-annual events of interest to climate finance geeks like me, ratings agency analysts, bank investors and regulators. Of themselves, they won’t matter much to home owners or the economy at large. They are worth watching, but not with a sense of dread or urgency.

That should be reserved for the mail box. And the letter with the cellophane window showing a friendly insurance company logo.

Meanwhile, the drums will beat louder for some sort of subsidised flood insurance or managed retreat where the taxpayer at large steps in to help land owners retreat, largely by paying them much more than their land is worth, or takes on the risk of repairs and replacement for bigger and more regular floods.

That again raises questions about the winners and losers. Renters will end up paying through their income and GST taxes to ensure owners of land endangered by climate change that we all know about and understand now can be rescued from ‘acts of god.’

Ka kite ano

Bernard

The climate landmine under our economy (a housing market with bits tacked on)