Welcome to My Net Worth, our regular column on the lives and motivations of our country’s top business, legal and political people in their own words.

Phil Goff’s path to some of the highest roles in New Zealand politics began when he joined the Labour Party in his mid-teens. After being kicked out of home while still at Papatoetoe High, he flatted with a future prime minister and immersed himself in political action and the anti-Vietnam War movement, all the while studying politics at the University of Auckland; he graduated with a master’s degree with first-class honours. In 1981, he was elected MP for Roskill, and three years later, aged only 31, became one of the youngest-ever ministers of the Crown. In total, he served in the Cabinet for 15 years, holding demanding portfolios including Employment, Education, Justice, and Foreign Affairs and Trade. He was also leader of the opposition for a term. In 2016, he stood for the Auckland mayoralty against 18 other candidates and won with 47% of the vote. He has yet to say whether he will stand next year for a third term, having been tipped to become the next ambassador to the United States. He and wife Mary have two sons and a daughter and own a farm near Clevedon.

I had a pretty normal upbringing. We were a working-class family, with a three-quarter-acre section in [Auckland’s] Three Kings with a horse and some sheep. It all seems like a different world now. In some ways, it was a poorer environment because it was very monocultural and there was not much concept of environmentalism in those days, but it was a stable post-war upbringing.

My dad, Bruce, was a tradesman and there was an expectation that I'd be one, too. Then I was interested in animals, so I thought maybe I'd go farming, and then I got ambitious and thought maybe I'd be a vet.

I wasn’t shy, but not overwhelmingly confident either. I declined to become a prefect at school; I thought it was too much part of the establishment. I was quite politically active at school and joined the Labour Party when I was 15.

I learned about work ethic early on and learned to be resilient and independent. That came from being kicked out of home at 16 and having to put myself through the last year of school and university by working in the freezing works and doing cleaning jobs at night. I went flatting with my brother, Warren, whose flatmate was a guy called Mike Moore [prime minister in 1990] – he was an early mentor and inspiration.

I wouldn't have described myself as hugely ambitious. I kind of fell into politics rather than going in with an ambition. I was interested in the issues rather than the career. I remember people saying to me when I went to Auckland University, “What are you doing at university?” and I’d say, “Politics”, and they would say, “Well, how are you going to get a job with that?”

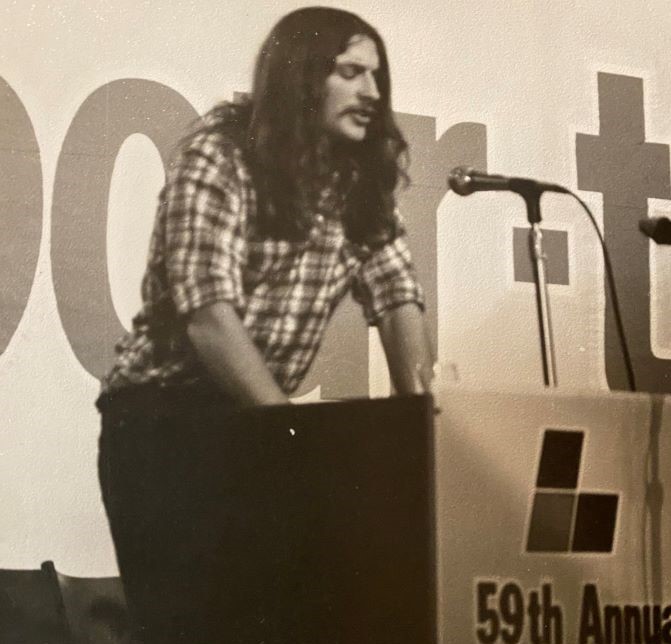

Phil Goff addressing Labour's Annual Conference in 1975.

Phil Goff addressing Labour's Annual Conference in 1975.

I think the biggest success in life is if you can develop a relationship that’s sustainable and lasting, a loving relationship, as that's pretty important as a bedrock of your life. I’ve been with my wife, Mary, since she was 15 and I was 18.

I’m proud of things where I feel that I did make a difference. That satisfaction compensates for the unsociable life that you have, with long hours and the degree of abuse that you always suffer in public office. You can say, “Look, I did the things that I thought were right. Some things I didn't achieve, some things I did, and what I did achieve, I think, were worthwhile and made a difference.

I suppose the biggest failure was when I had three years in what's commonly regarded as the worst job in politics – leader of the opposition – without getting the benefit of the reward of becoming prime minister at the end of it.

Failure is a funny thing. If you didn't have failures, you wouldn't develop humility, and humility is a good thing. You can let a job go to your head and think that you're important when, really, it's the job that's important. Failure helps you keep your feet on the ground.

1990 was not a great year for the Labour Party, with the divisions and then the country running into recession. I kind of saw it coming. I stopped being Minister of Education on the Friday and on the Monday I started work teaching at AUT, which was quite a big transition. In some ways it was good to have a break. But I found myself yelling at the radio in the morning and realised that I wasn't going to stay out of politics. I didn't want to be sideline critic, I didn't want to be a spectator, I wanted to be a gladiator.

I ride a motorbike. I've been doing that for 53 years. It makes me feel like a teenager again. It has quite a positive psychological effect.

To quote my father, “Every day you’re vertical is a good day.” I'm not ready to retire. But I'd like to get a bit more work/life balance. I said to my kids, “I didn't have enough time with you. But, you know, I'll have a lot more time with my grandkids.”

As told to Jacqui Loates-Haver.

This interview has been edited for clarity.