Depending on whom you ask, lobbyists are crucial to the smooth functioning of democracy, little better than a necessary evil, or back-slapping members of a mercenary old boys’ club. In order to shed light on what’s often perceived as something done in the shadows, we asked someone who has been lobbied, someone who works as a lobbyist, and someone who uses a lobbyist how the system has worked for them.

The Lobbied

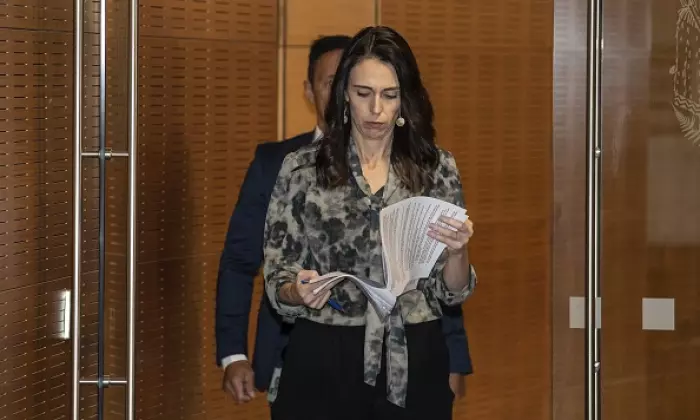

Tau Henare, former cabinet minister and now a panellist on Radio New Zealand’s Party People.

“I had a policy to accept everyone who came through the door,” says Tau Henare, describing a scenario that would seem to undermine the lobbyists’ reason to exist. “I didn’t pick and choose who had access. I had big tobacco, small tobacco, big oil, little oil. They never owned you, and you never expected anything from them. Maybe at Christmas there was a box of beer from Lion Breweries.”

You didn’t need to be a wily Machiavellian operator to get to Henare, a veteran of 15 years in parliament, representing New Zealand First, Mauri Pacific and the National Party. “I opened the door to people and we had a discussion. Nobody was donating anything to my campaign and that’s the way I liked it. From the big people down to the little person, anyone who wanted to have a yarn could.”

He says it worked also because the rules were clear. “You can’t do the game of politics behind a dark curtain. Before we got down to business, I’d say: ‘I can’t promise anything.’ In my first week as an MP, I was offered thousands of dollars by a taxi driver who wanted some immigration favours and I just laughed. I never heard from him again.”

Former cabinet minister Tau Henare. Photo: Getty.

Former cabinet minister Tau Henare. Photo: Getty.

Lobbyists never had to wait long to find out if they were wasting their time: “I would say, ‘Tell me what you want and I will tell you if I agree or can deliver.’ I see that as part of the run-of-the-mill job description of an MP.”

A well-prepared lobbyist can have an impact, he says. “Once, someone who was pro-nuke wanted to see me. I believed it was all wrong, but after we sat down and he gave me the run-through, I was ready to sign up.”

Henare believes that there were, and still are, lobbyists with access to senior figures in government whom even MPs in their own party have trouble reaching.

“If I needed something, there were a couple of people I would go to high up in cabinet, and they would tell me if I could do something, but I was never part of the crowd who runs the show. There were fewer than 10 people running the agenda.”

Meanwhile, people from both sides of an argument could get a hearing from him. “One day, I met with Philip Morris [tobacco company] in the morning and ASH [Action on Smoking and Health] in the afternoon. I had an ashtray on my desk in those days.” What came of that? “Nothing, really, because I couldn’t deliver what either of them wanted.”

Not for him the career path that sees lobbying as a good retirement option for politicians. He cites a former colleague who, “because he was an ex-MP, he could get access, and he used to wander around the place like he was part of the furniture”.

He says some influencers have more sway than others. Sometimes, only the names change: “You had the Christian brigade 30 years ago who had an in with politicians. Nowadays, Destiny Church has an in with some of the MPs.”

The Lobbyist

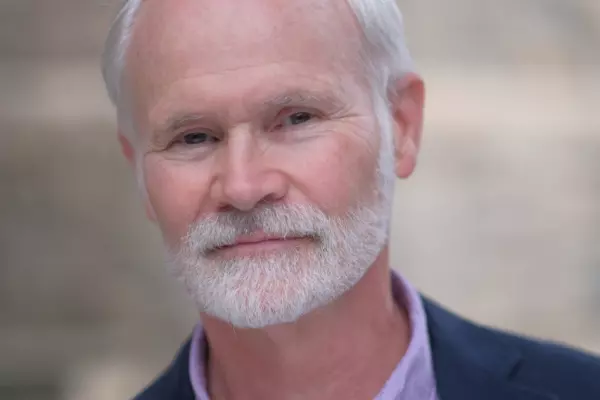

Mark Unsworth, co-founder, Saunders Unsworth, government relations consultants.

Former parliamentary private secretary Mark Unsworth’s company meets Henare’s requirement of transparency. It lists those it represents or has represented – all 168 clients – on its website.

Unsworth defines his craft as “someone who assists a client to get a point across to someone in a position of power and influence and gets paid for it”. He is quick to dispel the image of the lobbyist as the person whispering in an MP’s ear. “It’s all a bit of a day-to-day grind, with a lot of lobbying with government experts and officials and select committees."

Often, it’s not who you know, it’s what you know: “Any lobbying firm gets used by clients for day-to-day gossip and rumours. They want to know what’s going on around parliament and our job is to be ahead of the public information. It can help a business run smoother if they know things in advance.”

But who you know also comes in handy: “There is an element of value billing – if you have built up a relationship over years with someone to the point they have trust and faith in you and you can get hold of them in a short space of time and get a response, there is value in that.”

Unsworth really does know everybody. “I sit down with everyone face to face when they are new. [Press] gallery journalists don’t care about backbenchers, but I try to find out what they are like as people and write a couple of pars on each one. For 20-something years I have been doing this and only two have said no. One was a National MP, and his wife rang me up and went through things with me.”

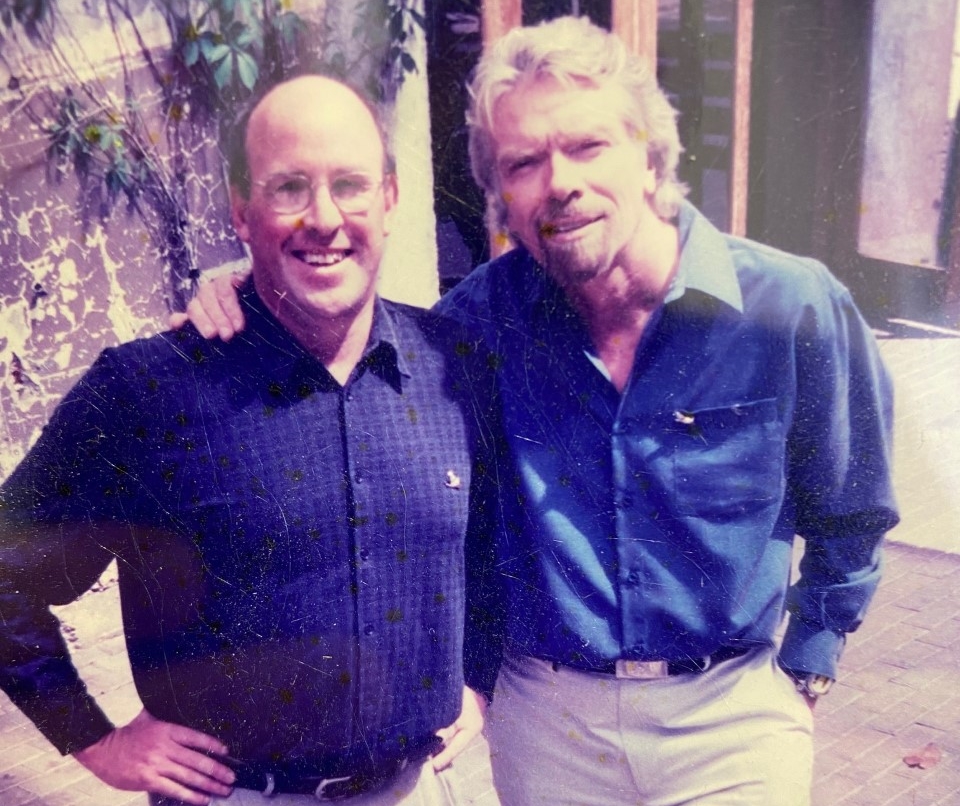

Mark Unsworth with Virgin Group founder Richard Branson.

Mark Unsworth with Virgin Group founder Richard Branson.

There is a skill in knowing who to know and keeping them on side: “The important thing is what level the decision is being made at. It may be at government department level. Nine times out of 10, the client might come in wanting to see the minister. ‘No, you need to see this person in the ministry.’ They will be in the room when you talk to the minister.”

He emphasises that much of a lobbyist’s time is still spent with government departments and officials and select committees, even under covid restrictions. “The thing that is different this time is the small number of decision-makers. There has not been as much parliamentary involvement under covid. Take the booze thing. In the first covid lockdown there was quite a bit of debate about what shops could open and what couldn’t. Supermarkets obviously could. The anti-alcohol lobby was jumping up and down saying people were drinking too much and began a campaign not to let bottle stores open. Anomalies appeared with the regulations that MBIE had hastily prepared, which involved different rules for bottle stores that had a retail shop and those that were online only. When Cabinet finally ruled on it, they made the call that the restriction on sales would be three bottles of spirits per person at any one time - the same as for duty free. But even then, there was still months of decision-making on whom it applied to and how it would work.”

The Lobbyer

Julian Davidson, former CEO of Independent Liquor/Asahi and a long-time client of Saunders Unsworth.

For Julian Davidson, whose career before Independent Liquor included time with Lion Breweries, choosing a lobbyist was a case of who he knew.

“I think I knew Mark Unsworth from Lion days,” says Davidson. “I had worked with other lobbyists before Mark and he was far superior to anyone else I used.”

As a sector with a big social responsibility component, the alcohol industry needs to have good relations with the government. Davidson had seen the Australian industry blindsided by government moves on ready-to-drink (RTD) alcohol mixes.

“We knew we had to stay ahead of the curve in relation to changes that could flow on to New Zealand. People have polarised views on RTDs and we needed a lobbyist to be pro-active.”

Which Unsworth was. “Between Mark and me, one of the outcomes of this exercise was New Zealand’s first genuine voluntary industry code for manufacturers, which we at Independent Liquor/Asahi led, with his help.” (Among other things, the code limits the alcohol content of RTDs.) Davidson says that solution is still functioning.

Julian Davidson, former CEO Independent Liquor/Asahi.

Julian Davidson, former CEO Independent Liquor/Asahi.

He also knows how lucky he was in his choice of lobbyist: “There are bad players who can get you to someone to have dinner and to hatch a plan. We never did that. It was never done over glasses of whisky. It had to be out in the open. We had a red face test – how would you feel if it was in the paper the next day?”

Davidson is sceptical that a “just walk in and sit down with your MP” approach is workable. “It is too labour-intensive. We have people to do all sorts of things in an ordered society. If access was as easy as that then the lobbyist movement wouldn't exist. If you have a lobbyist with respect from both sides – government and industry – and they can say, ‘I think you should listen to this’, you are making the process more efficient.”

Networking was nevertheless important to the success: “My engagement with Mark went through to sitting down with government people, caucus members, the opposition caucus, civil servants in Justice and Health. There was an element that was sometimes linked with social events. Mark would say, ‘This will be useful to attend’, but it was never an environment where you go into a corner and cook up a deal.

“I hired Mark on the basis that the biggest value a lobbyist can bring is they can give you the opportunity to formally engage with parties, and that only comes about through longevity, trust, respect and informal networking.”