Knowing how COVID-19 affects global mortality rates is crucial if we are to understand the factors that govern its spread and severity, and to be able to evaluate the effectiveness of government responses to the pandemic. In May, a team of researchers led by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs published the first results from their attempt to estimate global, COVID-19-related death rates. Writing in Nature, Msemburi et al.1 present these estimates in more detail.

Read the paper: The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

Many deaths from COVID-19 went undetected in official reports from 2020 and 2021, because of limited testing capacity and misclassification of causes of death. This lack of data makes it challenging to quantify the mortality toll of short-term events, such as wars and natural disasters, as well as pandemics. For this reason, excess mortality — defined as the difference between all observed and expected deaths in a given period — is considered the gold-standard approach for estimating the mortality toll of short-term events2,3. But it is hard to find a universally effective way to measure excess mortality4,5, because there are substantial variations in underlying mortality trends and data availability across populations.

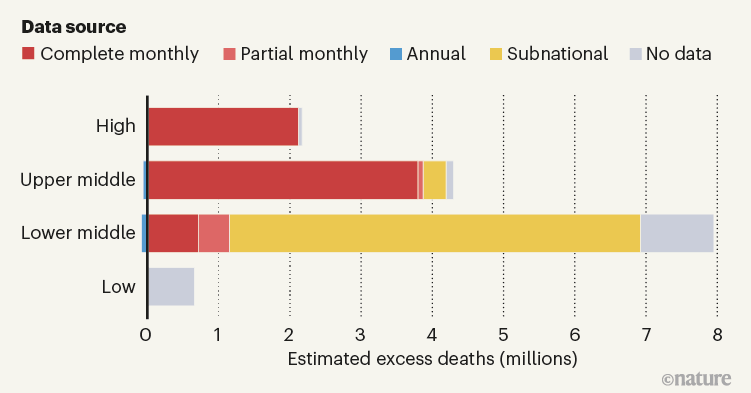

Msemburi and colleagues set out to estimate excess deaths from COVID-19 for every country in the world. The authors report that there were between 13.2 million and 16.6 million more deaths than expected in 2020 and 2021. This death toll was between 2.4 and 3.1 times higher than the officially reported number of COVID-19-related deaths. Four out of five excess deaths occurred in middle-income countries (Fig. 1), with some of the worst affected in Latin America. In both years combined, the observed mortality in Peru was double the expected level, and it was between 41% and 51% higher than expected in Mexico, Bolivia and Ecuador. Low-income countries had fewer deaths, mostly because they account for only 9% of the global population, and have younger populations, on average, than do higher-income countries. Compared with the published data, Msemburi et al. present more-detailed methods and more-refined estimates, by adjusting the way in which underlying mortality trends were forecast for several countries6.

Figure 1 | Country income level and estimated excess deaths from COVID-19. Msemburi et al.1 estimated the number of excess deaths that occurred in every country in the world in 2020 and 2021. Here, countries are grouped according to their income level (high, upper middle and so on). The authors made their estimates using monthly, country-level data on the total number of deaths where available. However, they had to make estimates of excess deaths from incomplete data for most countries. For some, data were available for only certain months or as annual data. More problematically, in many countries, data were available on only a subnational level, or not at all. Globally, half of the estimated excess deaths came from these countries, with this proportion varying hugely by the country’s income level. The authors’ estimates involved subtracting negative excess (where there were fewer than expected deaths) from positive excess, meaning that for some subgroups (such as annual upper middle and lower middle), the overall number of deaths is negative. (Figure generated using data from Supplementary Tables 5–13 of ref. 1.)

However, the authors’ estimates must be interpreted with extreme caution. This is because only 37% of countries had complete data for the number of people who died from any cause in each month of 2020 and 2021 — an essential figure for accurately calculating excess mortality. There were no data at all for 43% of countries; 2% of countries had data for only some regions; 5% had only annual data; and 13% had incomplete monthly series. The availability of data is heavily correlated with income. For example, only 2% of European countries had no data for 2020, whereas for African countries this figure was 87%.

As a result, the authors had to make some problematic inferences. First, for countries that lacked data in some regions, they had to scale death counts from subnational to national levels. This assumes a constant share of deaths between regions before and during the pandemic. But the spread, timing and severity of COVID-19 within countries was far from uniform7,8.

Precise mapping reveals gaps in global measles vaccination coverage

Second, the researchers had to infer the number of expected and excess deaths in countries with no mortality data (mostly low-income countries) by extrapolating patterns from those with more-complete data (mostly high-income countries that have robust health-care systems). The researchers adjusted the patterns seen across the latter group to make estimates for the former using country-specific proxies for socio-economic conditions, the intensity of the pandemic, each country’s susceptibility to COVID-19 and its capacity to respond to the crisis. As such, half of global excess deaths were estimated without data on mortality, or by using data from subnational regions (Fig. 1).

There are other factors to consider when interpreting Msemburi and colleagues’ findings, including ‘avoided’ and ‘displaced’ mortality. The former refers to expected deaths that did not occur — for instance, influenza-related deaths that were avoided in 2020 and 2021, owing to changes in people’s behaviour and social-isolation measures9. The latter refers to deaths of frail or sick people that were expected to occur during the observation period, but were brought forward by COVID-19, producing a temporary surplus in mortality followed by a deficit, and consequently ignored when calculating cumulative excess deaths.

Msemburi et al. did not adjust for these factors, because they aimed to identify all changes in mortality during the pandemic. Nevertheless, adjusting estimates for these numbers is essential if the goal is to understand COVID-19 fatality better. There are already models available that can adjust for influenza-related avoided mortality10, and new approaches have been proposed for use in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic11. For displaced mortality, partial adjustments can be made by excluding mortality deficits when computing the cumulative number of excess deaths over the months of the observation period. (The adjustment is only partial because COVID-19 deaths that occur during periods of overall deficit remain uncounted.)

A reconstruction of early cryptic COVID spread

Although the inferences made by Msemburi and colleagues are not ideal, there is no obvious alternative. However speculative these estimates, most are surely closer to the truth than are officially reported numbers of deaths from COVID-19. To rely on confirmed deaths would imply that the pandemic spared low-income and lower-middle-income countries — vulnerable populations that have limited capacity for testing and response. This assumption is highly implausible, and even irresponsible.

Nonetheless, the complexity of the task is apparent from the fact that similar attempts to estimate the effect of the pandemic on global mortality have given different results. For the same period, the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle12 estimated 18.2 million excess deaths, and The Economist magazine estimated 16 million (see go.nature.com/3uykedp). This makes the WHO estimate the most conservative of the three. Compared with these other studies, the approach adopted by Msemburi et al. is simpler, and their estimation of uncertainties is more rigorous.

A sensible next step for Msemburi and colleagues — and one currently under way (see go.nature.com/3vhmybu) — is to include information on age in their data. The risk of COVID-19 death increases with age13. Because the authors calculated excess mortality for entire populations, any difference between countries is affected by variations in their age compositions. There have been some attempts to rank countries’ response to the pandemic (including one in the current study) by estimated overall death toll, but without data on age, any assessments of differences in pandemic severity or the effectiveness of responses will be biased.

Finally, the complexity of estimating the effect of the pandemic on global mortality underscores the urgent need to build robust, centralized systems that allow for real-time monitoring of global mortality. The construction of such systems will require considerable global efforts to strengthen civil registration and crucial statistics systems worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries. But, once built, they will serve as an essential early warning for future pandemics and health crises.

Read the paper: The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

Read the paper: The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

A reconstruction of early cryptic COVID spread

A reconstruction of early cryptic COVID spread

Precise mapping reveals gaps in global measles vaccination coverage

Precise mapping reveals gaps in global measles vaccination coverage